The rise and rise of global anti-terrorism law

Contents

For many, the response to the 9/11 attacks in 2001 stands as the origin point of the ‘‘war on terror’’, marked by the growth of counterterrorism as a global legal framework.

However, a new book by Professor Conor Gearty, LSE Law School, uncovers a much older story behind the rise and rise of global anti-terrorism law. Introducing Homeland Insecurity at a recent Research Showcase talk, Professor Gearty explains how the book explores the ‘‘deeper legal history’’ behind the reactions to 9/11 and the laws governing counterterrorism around the world.

The very lack of a definition became my story

Defining terrorism

Homeland Insecurity was inspired by a much earlier book by Professor Gearty. Terror was published in 1991, and the backdrop of the book was the preceding decades of political violence involving Irish people. The 1980s bore witness to many violent events, including the deaths of 10 Irish republican prisoners through hunger strikes at ‘‘The Maze’’ prison (also known as Long Kesh) in 1982, and the attempted assassination of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher by the IRA in the bombing of Brighton Grand Hotel in 1984, in which five people were killed. For Professor Gearty, ‘‘that was the world I grew up in as an Irish person in Britain, and I tried to write a law book about it.’’

In writing Terror, however, Professor Gearty realised that ‘‘actually there is no subject really discernible to a lawyer called terror and terrorism’’. He describes being struck by the way that ‘‘terrorism’' was defined in dictionaries in the early 1980s by acts like Palestinian bombs in Israel, but the invasions of Lebanon in 1978 and 1982 by Israel were not mentioned under the same definition.

Interrogating this asymmetry in understandings of violence, Terror became an early example of ‘‘critical terrorism studies’’, which posits, as Gearty puts it, that ‘‘the value of the definition of terrorism is that it has no definition, that it is a malleable concept that can be deployed in the hands of power to suit and promote certain international interests or to secure coercive conduct against dissidents.’’ As he explains, ‘‘the very lack of a definition became my story’’.

Thirty years later, Professor Gearty considered writing a new edition of Terror – something he had never done with any of his other publications. But improvements in the literature on terrorism – with the launch of the Critical Terrorism Studies journal and particularly strong scholarship emerging from gender and race studies – meant a second edition didn’t seem necessary. Instead, three key ideas came together to inspire Homeland Insecurity.

Why does nobody in histories of terrorism talk about colonial violence?

The first idea was to examine anti-terrorism law, drawing on Professor Gearty’s legal expertise. Despite his critical stance towards definitions of terror and terrorism, Professor Gearty stresses that ‘‘anti-terrorism law does exist. It is a tangible thing. Police arrest people under it. People kill people under it.’’

The second idea was to specifically write a history of these laws – an overlooked topic since ‘‘historical context is rare in law’’. The third revelation was provoked by a question: ‘‘why does nobody in histories of terrorism talk about colonial violence?’’ With minor exceptions, the centrality of colonialism to the emergence of anti-terrorism law had been largely overlooked. Thus, Professor Gearty states, ‘‘I had my subject’’.

Asymmetrical warfare and imperial power

‘‘So why talk about colonialism?’’ The answer, Professor Gearty explains, is that the violence of colonialism – whether committed by the British empire, or the French, Dutch and German empires – led colonial subjects to develop strategies of resistance. Assassinations, selective explosives and other covert acts of violence became a strategic approach to resisting the military might of colonial forces. The imbalance between the military superiority of colonial forces and the tactics used by colonial subjects led to the birth of ‘‘asymmetrical warfare’’. Professor Gearty makes clear that ‘‘asymmetrical warfare is what we call terrorism … imperial power gave the name ‘terrorism’ to that quite early on.’’

I discovered that the history of anti-terrorism law starts from laws that were passed to try and control resistance to imperial power where the resistance took the place of unorthodox violence.

Initially, resistance to colonial violence was dealt with by raw imperial power, such as military rule or martial law. However, Homeland Insecurity shows how the aftermath of World War One saw the emergence of a new legal framework for dealing with asymmetrical warfare. As Professor Gearty explains, ‘‘I discovered that the history of anti-terrorism law starts from laws that were passed to try and control resistance to imperial power where the resistance took the place of unorthodox violence.’’

Professor Gearty cites many examples of how ‘‘the control of colonial insurgency becomes something dealt with by law’’ following World War One. The emergence of ‘‘the modern anti-terrorist legal structure’’ can be seen in the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, passed in 1920 by the UK Parliament during the Irish War of Independence; the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act imposed in 1919 in India under British colonial rule; and the international League of Nations draft convention on terrorism. The panic in the 1920s and 1930s around terrorism meant ‘‘you see a whole move towards the legalisation of counterterrorism’’.

Rather than being a contemporary phenomenon, then, anti-terrorist law is ‘‘an old story’’. And, Professor Gearty explains, ‘‘that old story is one of the main reasons why it’s been so easy to embed the ‘war on terror’ in our culture’’ following the 9/11 attacks.

The liberal duplicity of anti-terrorism

For Professor Gearty, the roots of counterterrorism in colonial histories show the hypocrisy in our understandings of terrorism and the consequences of the legal framework established to prevent it. He argues that the legal structure surrounding counterterrorism and what is seen to be justified in its name serves as ‘‘a reminder of a duplicity at the core of liberal democracy, which is that liberalism is only for the home team, and liberalism does not apply to the away team’’.

It is this idea that gives the book its title, Homeland Insecurity. The title reflects how ‘‘the book is a study in the contrast between the liberty and the liberalism and the rule of law that is within the jurisdiction of the imperial power, and the treatment of the colonial subject who is not quite ‘home’ but not quite ‘away’.’’

This ambiguous status of being ‘‘home/away’’ meant colonial subjects ‘‘could be shot, they could be court-martialled, and somehow or other liberal society is able to believe that it’s liberal while doing this in the 20th century’’. This treatment of those deemed ‘‘the enemy within’’ under the guise of anti-terrorism has continued into the 21st century and ‘‘the unspoken driver … is race’’, argues Professor Gearty.

Global anti-terrorism law today

What is the state of anti-terrorism law today? Speaking of the overwhelming devastation being seen in Gaza and throughout Palestine, Professor Gearty argues that the situation is striking as Israel appears intent on discarding this legal framework.

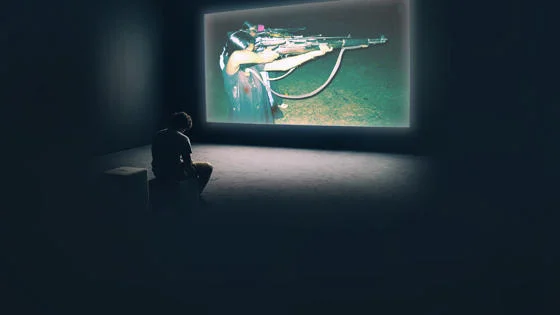

Professor Gearty notes that Palestine was central to the writing of Terror back in 1991. He explains how ‘‘the Palestinian movement was successfully redescribed not as a guerilla separatist movement engaged in a people’s right of self-determination but as a global terrorist movement’’ in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with this repositioning led particularly by Israel and the US. Unlike groups like the IRA, parts of the Palestinian movement chose to deploy serious violence internationally through the use of modern technology in this period. When this violence was broadcast globally through the relatively new medium of television, Western powers viewed it as threatening ‘‘some kind of world contagion of terrorism, of violence’’. Professor Gearty states that this lens was used to legitimise a counterterrorist response.

Yet, what is so notable about today, Professor Gearty argues, is that ‘‘Israel and America have largely given up trying to pretend there’s a legal basis for what they’re doing … there is no longer any plausible, even implausible effort, to locate it in law. It’s raw power.’’

The aftermath of World War One marked the emergence of anti-terrorism laws, and the early 21st century witnessed their intensification through the ‘‘war on terror’’. What we are now seeing, Professor Gearty concludes, is ‘‘a desperate situation, the normalisation of the destruction of a country in real time, done by us in the name of counterterrorism. It’s shocking.’’

This LSE Research Showcase was written up by Rosemary Deller, Knowledge Exchange Support Manager at LSE.

Download this article as a print-optimised PDF [216KB].