Inequality, insurgency and conflict: searching for justice for indigenous peoples in India

Contents

When 84-year-old human rights activist and Jesuit priest Father Stan Swamy was imprisoned and died in judicial custody in July 2021, many people across the world mourned the loss of a man dedicated to improving the lives of some of the most disenfranchised in India, and the wider challenge to democracy in India.

Father Stan was one of at least 16 intellectuals imprisoned since 2018 for alleged terrorist activities related to caste-related violence at Bhima Koregaon. The scholars, lawyers and human rights activists detained in the aftermath were accused of having provoked the violence, and for having links with Naxalites – banned Maoist insurgents who have been fighting the Indian state for decades.

We are now seeing a new authoritarianism on the rise in India, one that has parallels in so many other places in the world.

Helping the indigenous population understand their constitutional rights

One of those shocked by the news of Father Stan’s imprisonment and death was Alpa Shah, Professor of Anthropology at LSE. Professor Shah first met Father Stan in 2008, when she was living with the indigenous people of Jharkhand. The Adivasi, tribal people who live outside the caste system in central and eastern India, are among the most neglected groups in India. Their forests, which are rich in mineral reserves, are the heartlands of the Naxalite insurgency.

Professor Shah dismisses the Indian government’s claims of terrorism against Father Stan, highlighting instead that it was his work helping the indigenous people of India that made him vulnerable to state oppression. "Father Stan was among those activists working with the Adivasi to educate them on their constitutional rights, particularly with regards to protecting their land, as multinational corporations aided and abetted by the Indian state tried to grab it," she says. "It was this work that the state was trying to suppress."

The Naxalites, Professor Shah explains, are a cohort of Marx, Lenin and Mao-inspired ideologues and tribal combatants whose stated aims are to overthrow the current political system and break the structural barriers that keep the lower castes marginalised in order to create a more egalitarian society.

Although Naxalites consider themselves a movement promoting equality, in practice, patriarchal attitudes are still common, and have impacted on the indigenous communities they live with.

Spending time with the Naxalite guerrilla group

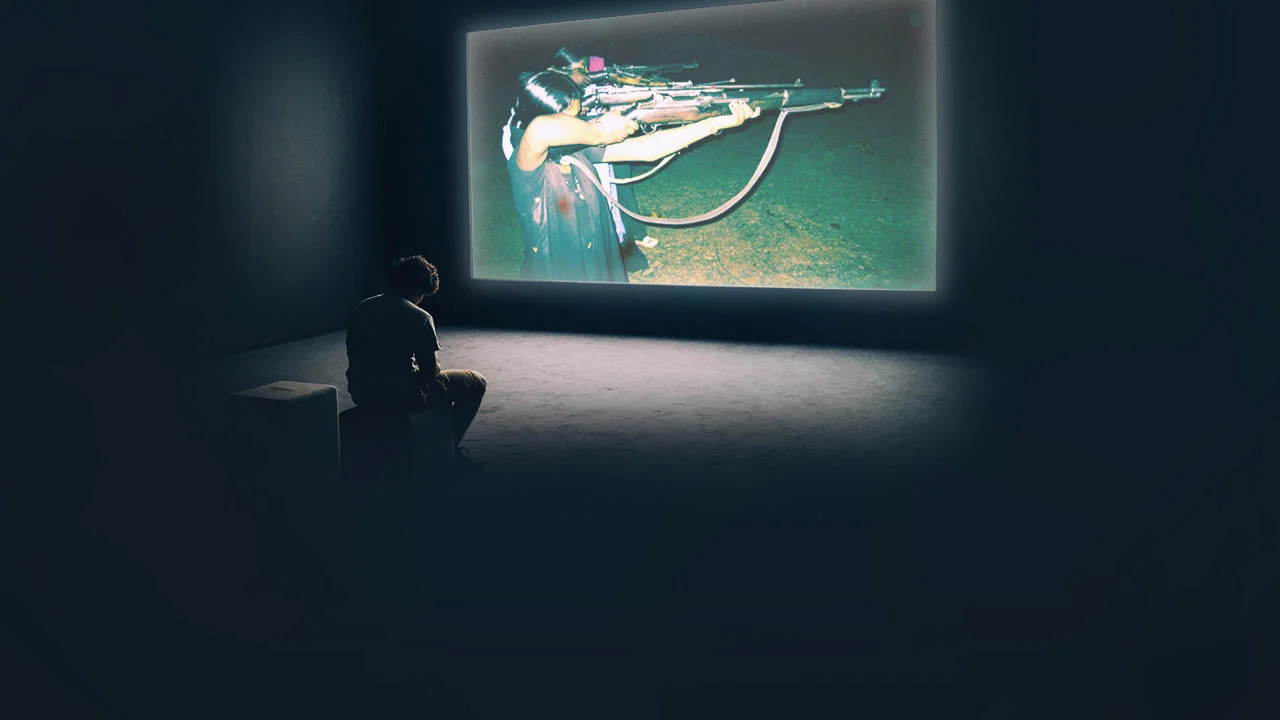

Professor Shah spent four and a half years living in Jharkhand to understand the lives of the indigenous tribes and the insurgents that lived amongst them. Her resulting book, Nightmarch, details a seven-night trek she took with a Naxalite guerrilla platoon and explores how their left-wing ideology has spread amongst the forest’s indigenous populations, whose lives have become embedded with this Maoist movement.

While the Naxalites are often portrayed either as immoral terrorists or as selfless "Robin Hood" figures, reality is far more nuanced, explains Professor Shah. "From the beginning, the Naxalite cause attracted educated, urban youth from dominant caste backgrounds, drawn by the romance of renouncing their home comforts to fight in a revolutionary movement for a better world," she explains. "But over time, low caste and tribal peoples have also joined the fight. Some of India’s most disenfranchised people are now involved."

While this mix of people from castes and backgrounds fits the organisation’s egalitarian message, the realities of life within a military organisation do bring up contradictions and difficulties, she says.

The danger of reproducing old inequalities around caste, tribe and gender

"The Naxalite aims are noble, but they are living under intense state repression, and within those conditions it is easy to replicate this violence. It’s also easy to reproduce the inequalities around caste, tribe and gender, even though as a group they are committed to overturning the inequalities that keep indigenous people so disenfranchised."

One of the areas where this can be seen is that of gender equality, she explains. "Although Naxalites consider themselves a movement promoting equality, in practice, patriarchal attitudes are still common, and have impacted on the indigenous communities they live with," she says. One example detailed in Nightmarch is the Naxalite response to the Adivasi practice of women and men drinking together - the group’s firm anti-alcohol stance leading it to respond with violence damaging gender relations amongst the Adivasi.

The Adivasis are standing in the way of an economic boom that will benefit these ruling elite.

Although the movement has become intrinsically bound to the indigenous people of the area, there is also a contradiction to their taking up the fight in Adivasi lands, the book suggests. While the group aims to bring communism to the people, Professor Shah explains, they are also unable to sustain themselves without implementing a form of "taxation" – demanding a percentage of all moneys from development projects and large-scale capital accumulation made on insurgent-held land. Many of the forest-based Adivasi communities, however, were already relatively egalitarian in comparison to the caste-based hierarchy of the Indian agricultural plains, meaning that it is the Naxalites who have exposed them to capitalist values and caste hierarchies. These values are taken up by some, potentially undermining the movement’s communist aims.

While Professor Shah explores the potential for these contradictions to damage the guerrilla group itself, she is also keen to stress that the reason behind the Indian government’s response to the rebels is firmly about corporate capital accumulation. "The Indian government has labelled the Naxalites terrorists and run brutal counterinsurgency campaigns to wipe them out, partly because of ideological differences and out of a desire to maintain power. But there is also a strong economic factor in the government’s interest in the area and the Naxalites," she says.

"Adivasi lands are rich in minerals and very lucrative for the national and multinational corporations hovering over them. The Adivasis are standing in the way of an economic boom that will benefit these ruling elite – and consequently, so are the human rights activists seeking to help them understand and fight for their rights."

With this recent action, the government has put in prison all these people who represent major facets of the fight for democracy in India and for the fight for human rights.

Why is the Indian government targeting human rights activists like Father Stan?

And so we return to Father Stan and the other activists, lawyers and intellectuals jailed under anti-terror laws. "With this recent action, the government has put in prison all these people who represent major facets of the fight for democracy in India and for the fight for human rights," Professor Shah explains. "It’s a warning to everybody working on the ground – you get in our way and we’ll put you in jail."

It is this government response that has led her to highlight the activist’s work on the ground to support India’s indigenous population. "As an anthropologist, most of my research has been to date based on indigenous rights and on the experiences I’ve had living with indigenous people," she says. "Through that, I came into contact with a whole range of people, including Father Stan, who were fighting for those rights."

Many of these people, Professor Shah explains, are now in the state’s sights, imprisoned for potentially many years before a trial is even begun. It is these connections that led her to explore Father Stan’s activism in a recent article published in the New Statesman and in the new preface to the UK paperback edition of Nightmarch to be published this month. "Democracy has never been perfect," she continues. "But we are now seeing a new authoritarianism on the rise in India, one that has parallels in so many other places in the world."

"It’s important to understand the contributions these activists have made to Indian life, but there is also a wider message, which is what their lives and work can tell us about democracy in India and its unravelling."

Professor Alpa Shah was speaking to Jess Winterstein, Deputy Head of Media Relations at LSE.

Image: Alpa Shah

Download a PDF version of this article