Rethinking anticolonialism: what can we learn from Egypt’s political journey?

Contents

Egypt’s moment of decolonisation in the 1950s-60s has been central to Egyptian politics and society, and I have always felt that the complexity, nuance, and contradictions of that particular era are important to flesh out, to admit, and to explore.

My book, Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt, emerged out of a haunting feeling that the politics of decolonisation and the project of the postcolonial state are still with us in many ways. Writing about an anticolonial revolution in the wake of the 2011 revolution was a strange process; I often found myself wondering if history was repeating itself. Yet as I completed the book, I began to notice how similar questions around social justice seemed to be present across both revolutionary moments, calling on us to keep them alive.

Perhaps the core theoretical question is what it means to position Marxism in the postcolony.

Theoretically, Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt is a book that seeks to focus postcolonial and Marxist scholarship on the Middle East. This book builds its analysis of the afterlives of Egypt’s moment of decolonisation through an imagined conversation between theorists Antonio Gramsci and Frantz Fanon around questions of anticolonialism, resistance, revolution and liberation. As such, it brings two critical canons into conversation – Marxism (Gramsci) and postcolonialism (Fanon) – through an examination of revolutionary events in Egypt across two revolutions: 1952 and 2011.

Gramsci is best known for his theory of cultural hegemony, arguing that the ruling class maintains power primarily through universalising norms and values related to their particular political project throughout society; in other words, through mostly consent rather than coercion. Fanon viewed colonialism as a form of violent domination, arguing that Western colonialist rule created a dependent "native bourgeoisie" which could never become hegemonic.

Thinking about theoretical conversations through an imagined conversation was important to me, because it allowed me to bring out the complex ways in which theoretical canons and theorists speak to one another, even when that speaking is through disagreement.

Perhaps the core theoretical question of Anticolonial Afterlives is what it means to position Marxism in a former colony, and what kinds of changes take place when Marxist theory and Marxist concepts travel. Exploring concepts by applying them to a particular time and place, the book speaks to debates around colonialism, postcolonialism and revolution in the Global South.

Because the book focuses on both Egypt’s moment of decolonisation as well as the 2011 revolution, it addresses a wide range of subjects during varying time periods.

The 1952 revolution, Gamal Abdel Nasser and modern Egypt's only period of hegemony

In my book, I argue that the Nasserist project - created by Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Free Officers - remains the only instance of hegemony in modern Egyptian history. Nasser began a period of modernisation based on Arab socialism, nationalism and independent economic development in Egypt following the revolution in 1952. The 2011 revolution signified the endpoint of its decline, decades after it was created.

Nasserism brought together economic development and state-led capitalism, political internationalism and Third Worldism (a political concept which emerged during the Cold War in an attempt to generate unity among the nations that did not want to take sides between the United States and the Soviet Union) and anticolonial nationalism into a powerful project that achieved high levels of consent across Egyptian society. This project declined following the 1967 defeat to Israel, and under President Anwar el Sadat in the 1970s and 1980s we see declining consent and rising coercion. The failure to maintain hegemony led to a time of crisis during which the ruling class had to instead turn to police force to maintain control. The subsequent presidency of Mubarak in the 1990s and 2000s saw increasing levels of police brutality, rampant corruption, poverty and violent electoral politics, ultimately culminating in the 2011 revolution.

Exploring issues of nationalism, capitalism, resistance and internationalism

Because the book focuses on both Egypt’s moment of decolonisation and the 2011 revolution, it addresses a wide range of subjects during varying time periods: nationalism, capitalist development, resistance, social movements, and global/local connections. It includes an analysis of the politics of decolonisation, Third Worldism, internationalism, the Cold War, the advent of the global neoliberal project, rising democracy movements, and the Arab Spring.

To understand these subjects, I examined both global and academic literature, as well as archives, interviews, and other forms of material from within Egypt. These enabled me to bridge the gaps that can often exist between theory and evidence when it comes to the Global South and the Western academy.

To do justice to immensely powerful and complicated moments in history - ones that I, like many others, am invested in and connected to - it was important to acknowledge the contradictions sometimes shown between theory and reality and to attempt to understand historical moments as they would have occurred, rather than through what we might want those events to be from the vantage point of the present. This meant being open to the materials I was finding and thinking with, and finding ways of writing in and through contradictions, rather than trying to resolve them.

Centering Egypt and the Global South

Finally, as a scholar from the Global South, I was conscious of producing knowledge and writing that took seriously events, experiences and intellectual lineages within Egypt itself. Despite my interest in thinking with Gramsci and Fanon, I sought to centre the Egyptian context and bring it into conversation with these theorists, rather than to interpret Egypt through theories that were produced elsewhere. In this, I attempted to create an imagined conversation both between Marxism and postcolonialism as well as between these theoretical bodies of work and revolutionary events, consciousness and memory in Egypt. I wanted Egypt to became part of the conversation, rather than a space to be analysed from a distance; a move that I believe holds great importance for scholarship more broadly.

Overall, I see this as a humble contribution to a bigger project around rethinking anticolonialism and its afterlives in the Global South, and how to think about this through local contexts, through contradictions, and through events in the present that are hauntingly similar to those that have come before.

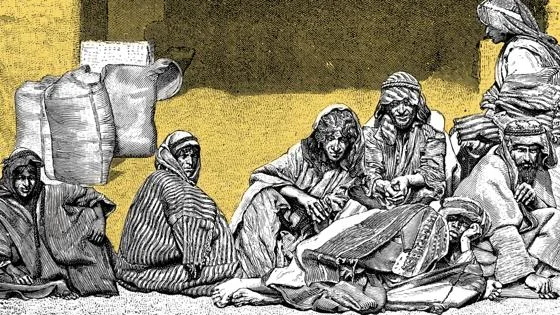

Image: Wikipedia (Gramsci and Fanon) and Flickr

Download a PDF version of this article