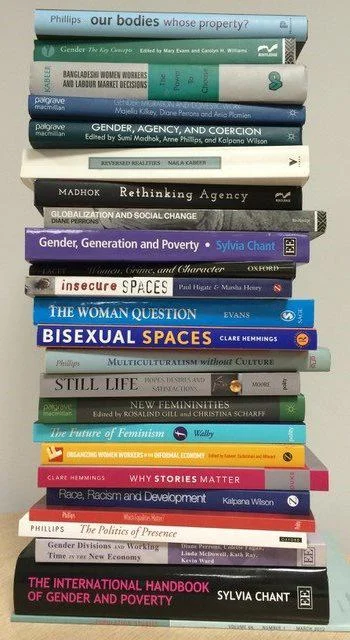

Research Breadth

LSE Gender Scholarship at 30

What does Gender Studies scholarship look like? The LSE Department of Gender Studies is the largest and most prestigious of its kind in Europe and second largest in the world. It is globally renowned as a world-leading base for research, teaching and wider engagement on gender, serving as a nodal point across the School and the higher education sector more widely. The research at the Department is classified into four broad streams of knowledge production: rights, security and development; memory, representation and culture; state, economy, families and inequalities; and subjectivity, sexuality and identity. This scholarship is rooted in a unique incorporation of the social sciences and humanities and in combining theory and practice with interdisciplinary and transnational perspectives. In its research and teaching, the Department’s transnational and interdisciplinary lens make its expertise and knowledge production vital to the study of gender power relations and gendered inequalities around the globe. Finally, the theoretical and empirical aspects of research in the Department are led by questions of social justice and the bettermentof society through critical engagement with knowledge and knowledge production in a period of rapid global transformations.

Our recent interventions into contemporary geopolitics of conflict, militarism, peacekeeping and security draw on feminist postcolonial frameworks to argue that peacekeeping studies must recover critical theoretical contributions that have been sidelined within the field. In The End of Peacekeeping, based on critical theory and ethnographic fieldwork on peacekeeping missions and training centres around the world, Dr Marsha Henry reveals that peacekeeping is not the benign, apolitical project it is purported to be, and encourages readers to imagine and enact alternative futures to peacekeeping. Such critical engagement is exemplified by Dr Aiko Holvikivi, who is working on a book based on fieldwork in East Africa, the Nordic region, West Africa, the Western Balkans, and Western Europe. Centring movements of knowledge and people in relation to gendered and racialised (in)security, the project extends a recent article that tracks the travels of the concept of gender in the training of military and police peacekeepers, arguing for continuing to contest what work gender can and cannot be made to do. Unveiling the logic of militarism, Dr Maria Rashid asks how does the military thrive when so much of its work results in injury, debility, and death? Combining testimonies of soldiers and their families as well as military archives in the Pakistan Army, Dying to Serve highlights how grief, sacrifice, anxiety, loyalty and respect underpin the military’s domination over state and society.

Departmental research engaging with social justice movements and counter-movements draws attention to another major area of contestation of our time – the struggle over the meaning of and space for democracy. One area of contestation is that of global governance frameworks, as interrogated by Dr Gloria Novovic. Research in Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda shows how the legitimacy crisis of global development is countered by gender equality actors towards global cooperation. Grappling with ethical-political principles, Dr Leticia Sabsay juxtaposes the mass feminist demonstrations against the rise of populism in Europe and the Americas, whereby cultural practices and popular mobilizations both exceed and question representative democracy's core conventions. The gendered psychosocial analysis of Ni Una Menosexplores the emancipatory potential of a political aesthetics that weaves vulnerability in opposition to the curtailment of bodily life along gendered, sexualized, and racialized lines. Political struggles are, of course, an ongoing concern. Dr Milo Miller’s research the Brixton Black Women’s Group (1973-1985) has highlighted the importance of distinct spaces for women of African and Asian descent to debate immigration, housing, health and culture and campaign for social change. Their writings are published in a new book, Speak Out!. Mapping and investigating transnational social movements has never seemed more important, as the current Departmental project led by Professors Clare Hemmingsand Sumi Madhok and funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council underscores. ‘Transnational 'Anti-Gender' Movements and Resistance: Narratives and Interventions’ brings together approximately thirty researchers from around the world, thirteen of which are LSE Gender-affiliated scholars. Their workjoins research and practice to better understand anti-feminist and anti-gender mobilisations globally.

In a world in which gendered and racialised vulnerability, precarity, harm and inequalities within and between societies deepen, our questions directed at the economies of care, of work, of inclusion turn a critical eye to simple binary distinctions. Researching anti-trafficking and women’s rights groups in the Philippines, Dr Sharmila Parmanand compares domestic and sex workers. This critical histography and ethnographic study argues that constructing a hierarchical relationship between domestic and sex workers entrenches precarity and normalises exploitation of feminized forms of work more broadly. How economic marginalisation is produced and how precarity and exploitation of labour are entangled with transnational mobility underpins the research of Dr Ania Plomien. A recent paper, developing the feminist critical political economy framework in examining the mobility of workers in food, housing and care provision between Ukraine, Poland and the UK, pinpoints the mechanisms through which markets reach deeper into the realm of social reproduction, thereby undermining the conditions for the societies’ ability to flourish. The movement of people, money, power and knowledge across borders interacts with and complicates local processes of change. Dr SM Rodriguez uses interviews, ethnography, and an analysis of fourteen years of Ugandan parliamentary records to show how The Economies of Queer Inclusion navigate domestic, anti-gay criminalisation and global inequalities reinforced by international financing on antigay ideologies and international human rights apparatuses.

Engagement with such complex global challenges demands conceptual and methodological innovation in order to expand the capacity of social sciences and humanities to account for the material and representational processes involved in gender social (in)justice. Professor Wendy Sigle, who argues that much of what can be found in the disciplinary toolboxes of demography (and other disciplines) reproduces problematic frameworks, accepts the kinds of questions that are worth asking and the methods that are commonly believed the most appropriate and rigorous. Yet, making space for a wider variety of critical contributions is necessary to inspire the extraordinary science needed in research and practice. This undertaking is cultivated by Dr Sadie Wearing, who examines the ways in which cinema, literature and popular culture both reflect and contest wider cultural dynamics. For example, the work of the British feminist socialist documentary film maker, Jill Craigie, serves to demonstrate how archival and film material enable a recalibration of the structure of feminist feeling, revealing not just gendered, but also class and race positionality that enables a more nuanced account of politics in film and the wider public. Experimenting with form and content by using storytelling, interviews and archival data, Professor Clare Hemmings applies an intersectional approach to the ‘memory archive’ revealing a complex inheritance of gender, class and race that characterises the present. Dr Carrie Hamilton explores the relationship between animal rights and other social justice movements, especially feminism, queer movements, sex workers’ rights, prison abolition and anti-racism. Veganism, Sex and Politics shows what is involved in struggling to live an ethical life in an unethical world, and inspires visions towards large scale social and political transformation. One such vision for equality and justice rests on engaging political theory and philosophy with ethnographic research on subaltern rights politics in most of the world conducted by Professor Sumi Madhok. Through tracking and theorising Vernacular Rights Cultures of subaltern social movements through a decolonial praxis we can formulate alternative imaginaries of justice and human rights.

Even a cursory overview of a small sample of the current conceptual, methodological and substantive LSE Gender scholarship stretches across a broad portfolio of issues and contexts. It is also a testament to Gender Studies wide-ranging contributions to debates about the most pressing issues of our time.