Our Origin Story

The history of Gender Studies at LSE

Introduction from Professor Sumi Madhok, Head of Department

Given its global stature and recognition, it is hard to believe that it was only 30 years ago that the Gender Institute, now known as the Department of Gender Studies, was born. In 1993-94, the interdisciplinary institute was set up at LSE to respond to the urgent need to research, teach and apply knowledge of the structures, formations and changes in gender relations around the globe; after all, gender is a key social structuring block of cultural, economic and political life. The early 1990s were led by a growing realisation among LSE’s leading scholars that the world’s only university devoted exclusively to the study of the social sciences could not afford to ignore global gender relations. Thus, the Gender Institute came into being as a result of the strong intellectual commitments of many globally renowned feminist, gender and interdisciplinary scholars across the School.

Over the years, the Institute grew from its initial staff of two people to become the largest gender teaching and research department in Europe, and by many indicators, the 2nd largest gender studies unit in the world. By all accounts it has been a very busy 30 years! In three decades, our students have gone into the world working toward a fairer and more just planet. LSE Gender’s alumni are not only academic leaders in university settings but also institutional heads shaping economic, political, and media activities around the world, with many more translating and applying the interdisciplinary, intersectional, transnational and anti-racist knowledge to transform professional and interpersonal engagements across all levels of civil society.

Departmental teaching at LSE Gender is, in the best LSE tradition, research led. The interdisciplinary intellectual life at the Department brings together social sciences and humanities, serving as a unique nodal point for gender research at the School, and underpinning its global recognition.

The three decades of teaching and research at Gender Studies – and the policy, political and community engagements that these enable – owes a great deal to individual and collective champions dedicated to institution building. The foremost among them, whom we lost earlier this year, should need no introduction to LSE colleagues and friends. But not everyone will know that Hazel was one of the two original people assigned to the department in 1994 and her commitment, enthusiasm and impact cannot be overstated. Hazel was not alone in this endeavour. As our origins story below details, many academics and administrators saw the importance of Gender and with this vision displayed extraordinary solidarity, commitment and effort contributing to our success. The legacy of this common purpose continues today with the invaluable work of our Advisory Board members. Do read our origin story below to get a glimpse of how the shaping of a field happens.

‘Origins’ written by Faith Armitage and Carolyn Pedwell (2005)

The early 1990s marked a time of great activity for scholars and students in the field of Gender Studies. In 1993, for example, the International Handbook of Women’s Studieslisted 74 Women's and Gender Studies courses in the UK, 47 of which were full Women’s or Gender Studies degrees, either at the diploma, undergraduate or postgraduate level. At the time, LSE was home to two of the UKs leading gender scholars: Henrietta Moore and Sylvia Walby. Moore's book, Feminism and Anthropology (Polity 1988), and Walby's, Theorizing Patriarchy (Basil Blackwell 1990), were both landmark works in the burgeoning fields of Gender, Women's and Feminist Studies. While Moore challenged the conflation of ‘woman’ and ‘gender,’ Walby effectively put ‘patriarchy’ back on the agenda. Also at LSE at this time were Sylvia Chant and later Jo Beal (joining LSE in 1994), who were developing innovative approaches to Gender Studies in a development context.

Moore and Walby, who were both instrumental in establishing the Gender Institute at LSE, remember that they were acutely conscious of the absence of Gender Studies at the School

'Here we have LSE, one of the premiere social studies institutions in the world, with leading gender theorists in several departments, but no discrete institutional framework for their research,’ recalls Moore. 'It seemed a bit strange, given that the early 1990s was the heyday of Gender Studies in the UK.’ Walby's assessment of the situation was blunt: ‘Not having Gender Studies here was a huge gap.'

But that was about to change. Professor Derek Diamond, vice-chair of the academic board of LSE, recalls that the board had identified Gender Studies, together with Development Studies, as two key areas for LSE to develop as interdisciplinary postgraduate research fields. Professor Lord Meghnad Desai presided over the inauguration of DESTIN, the Development Studies Institute, in 1990. However, he also managed to find time to promote the Gender Institute's creation during debates with others in the academic board:

'Feminism was the strongest influence on my thinking apart from Marxism and I had no problem keeping them both together in my head’, he recalls. ‘My reputation as an economist who could handle the technical mathematical stuff made me a good "bouncer" to keep the attackers of the GI off.’

As Desai's comments suggest, the view that it was important to establish cutting-edge interdisciplinary research institutes, such as DESTIN and the Gl, was not accepted by everyone at the School. Gail Wilson was a lecturer in the Department of Social Science and Administration at the time. She remembers a letter penned by one professor to LSE magazine, to the effect that Gender Studies was ‘like theology and had no place at a university.’ Wilson, who did not share this view, went on to secure the GI's first major research grant and helped gain University of London approval for the MSc Gender degree, as will be discussed below.

It is not surprising, in some ways, that there was resistance to the establishment of the Gender Institute. Not only is the research content itself potentially subversive and threatening to powerful interests, but so are the changes it introduces to research methods. As an academic approach, Gender Studies revealed the ways in which knowledge is deeply gendered. As Mary Evans (the first professor in Women's Studies in the UK and the external examiner for the Gender Institute from 1993 to 1995) argued in a 1997 article, ‘What feminists have done with the tradition of the critique of knowledge is to take the more radical stance of attacking not just the conclusions, the argument and the content of knowledge, but the very way in which knowledge is constructed.’

Gender theorists questioned the possibility of neutral, value-free methodologies and the academic separation of personal experience and emotion from theory. They interrogated the divide between quantitative and qualitative research, as well as traditional barriers separating ‘the researcher’ and ‘the researched.’ In effect, gender theorists were redefining ‘objectivity’ in ways that would radically transform conventional processes of teaching, learning and research. They were also demonstrating that ‘gender difference is an essential part of any discussion of the social or symbolic world.’ If this made Gender Studies seem threatening to those invested, for various personal and professional reasons, in the binaries which gender theorists sought to disrupt, it also made it innovative, in terms of both research and pedagogy.

Despite resistance to the Gender Institute's creation, many individuals at LSE evidently sided with Moore, Walby, Diamond, Wilson, Desai and others, in promoting the urgency and credibility of Gender Studies as a crucial area of social science research. ‘Nothing was producing nor likely to continue producing more substantial social change than the changing relations between men and women,’ Diamond argues. ‘And this is the point that ultimately persuaded the academic community.’

The changes in gender relations in the early 1990s that Diamond refers to were complex, and in some cases contradictory. On one hand, since the 1960s and 1970s when the Women's Liberation Movement gained strength in western, industrialised countries, several positive transformations in gendered relations had occurred. In the UK, increasing numbers of women had entered the labour market, achieved greater political representation within the parliament, and won key pieces of legislation promoting gender equality in employment and reproductive rights. Furthermore, by the mid-1990s, gender issues were gaining increasing significancein public policymaking at national and international levels, through domestic and international gender mainstreaming programmes, women's empowerment in the United Nations and the European Union and the insistence within World Bank projects on gender auditing. Within the realm of development, for example, policy and practice had arguably ‘become infused with gender.’ Thus, by the early 1990s when the Gender Institute was seeking formal recognition, ‘gender’ was on the way to becoming institutionalised in the UK and internationally.

On the other hand, this rosy snapshot of growing gender equality in the early 1990s obscured the contradictory nature of many of the celebrated advancements. It also effaced the effects of new and ongoing forms of systematic inequality and oppression that women (and other groups outside the white, masculine mainstream) faced around the world. As Ann Oakley and Juliet Mitchell argued in 1997, despite women’s increasing entry into the labour market in the early 1970s in western, industrialised countries such as the UK, ‘the proportion of women in full-time paid work had remained static for several decades.’ One of the main processes underlying this continuing inequality was the division of labour in the home which limits women's years of work experience and leads them to work on a part time basis. In addition, paid employment was highly segregated by gender with women overrepresented in lower paying jobs. Within the academy, women remained marginalised in many disciplines, if not completely absent.

If there was evidence in the domestic context to support the claim that gender inequalities required analysis, this was perhaps even more true in the international arena. Returning to the example of development, while issues of gender had gained visibility in international development and policy discourses in the early 1990s, the global gap between rich and poor had widened, with more women than men living in poverty than a decade before. Moreover, policy makers continued to operate with outdated concepts that obscured the gendered nature of poverty. As Sylvia Chant and others were arguing at the time, the normative concept of the ‘male breadwinner’, for example, failed to recognise the widespread occurrence of female-headed households and women’s immense non-market productivity. In this area, much more work was required to understand the ways in which women and men experienced poverty differently and unequally. Moreover, the exploitative aspects of international trade, migration and trafficking, were becoming increasingly pronounced in the 1990s, and were inscribing their oppressive effects on the lives and bodies of women (and men), especially those living in ’the South.’

Throughout the 1970s and increasingly in the 1980s and 1990s, many Black and lesbian gender theorists argued that such heralded advancements in gender equality — if they did bring positive change - often benefited a small minority of women (namely white, middle-class, heterosexual, able-bodied women living in the industrialised West) while continuing to exclude many ‘Others’. As these thinkers emphasised, analysis of how gender intersected with other axes of social differentiation, such as ‘race’, class, and sexuality, was necessary to theorise relations of power effectively in any arena of analysis.

To return to the Gender Institute's own story, in the context of dialogues about the validity of Gender Studies in the academy, scholars at LSE with an interest in gender organised a series of public lectures and seminars in 1991-92. Known simply as the ‘Gender Research Group,’ they secured some very prominent speakers. The line-up for that inaugural series included Michele Barrett, Joni Lovenduski, Anthony Giddens, Ruth Lister and Emily Martin. An estimated 150 people attended Professor Lord Anthony Giddens’s talk on ‘The Transformation of Intimacy: Gender, Sexuality, Democracy.’ (Then at Cambridge University, Giddens went on to become the director of LSE from 1997-2003.) The public lecture and seminar series created a buzz at the School, and as Gail Wilson recalls, ‘the after-lecture events were another important way of putting the Gender Institute on the map’. Thus, whatever particular scholars’ feelings about the legitimacy of Gender Studies as a disciplinary field, there was plenty of objective evidence — in the form of healthy attendance at lectures and seminars — of the keen interest in gender research.

A great deal of the credit for the success of the public lecture and seminar series must go to Hazel Johnstone, who has managed the Gl since its official inception. In 1991, Johnstone volunteered to coordinate the Gender Research Group's meetings and help plan its public lecture series, ‘I was working in the Geography Department when the gender research seminar and lecture series began,’ recalls Johnstone, ‘I'd always thought of myself as a feminist, so when I saw this initiative taking shape, I wanted to be a part of it.’ More than merely ‘a part’ of it, Johnstone's contribution to the Gl was and continues to be critical.

As Henrietta Moore puts it: ‘Without Hazel, there would be no Gender Institute.’

With the public lecture series up and running, the Gender Research Group turned its attention to the formal creation of an institute. The hard work of transforming mere interest in Gender Studies into a formal institution for gender at the School began.

In the autumn of 1991, LSE's director invited a proposal for the establishment of an Institute of Gender Studies at the School. Sylvia Walby, supported by others from the Gender Research Group, presented the academic board with the proposal. The proposal’s authors offered the following as the ‘Intellectual Rationale’ for the Gender Institute:

The analysis of gender (that is, the social relations between men and women) is currently an area of dynamic intellectual development. There are major changes in the relations between men and women, including the changing gender composition of the labour force, changes in the structure of the family, and increasing numbers of elderly in need of care. Political institutions at the national and international levels are adapting to these changes. These changes are interconnected and affect most other areas of social life. We cannot understand change in the modern world without the empirical and theoretical input from this field.

The explosion of analyses in the area of gender relations also derives from the fact that it has been intellectually underdeveloped, so there is enormous scope for new work. The neglect of analysis of gender has rendered inadequate many accounts of social, economic and political life. Many mainstream accounts treat the world as if it were peopled exclusively by one sex, men, to the detriment of the explanations offered. Most social science disciplines are now beginning to reconsider this absence and its implications for their intellectual work. It is not enough to compensate for this by studying only women. Instead, gender as a set of social relations needs to be analysed.

- Sylvia Walby et al, A Proposal for an Institute of Gender Studies at LSE, Oct 1991

The proposal also noted that LSE was already well positioned, in terms of its existing faculty, to cultivate gender-focused research: ‘There are already internationally renowned figures in the area at LSE... There are 28 teachers and researchers who list this as an area in LSE Calendar. But they are dispersed through the different departments at LSE and need a joint base’.

As the proposal pointed out, members of the Gender Research Group came from multiple disciplinary backgrounds. Sylvia Walby was based in Sociology, Henrietta Moore in Anthropology and Gail Wilson in Social Science and Administration. Other scholars who became involved in establishing the Gl included Jan Stockdale and Cathy Campbell from the Department of Social Psychology, Derek Diamond, Sylvia Chant and Simon Duncan from Geography, and Fred Halliday from International Relations. The inter-departmental links existing within these founding group members demonstrated that the interdisciplinary research and teaching agenda that LSE sought was, in many ways, already in place.

The LSE Appointments Committee formally approved the proposal to establish the Gender Institute in November 1991 and called for the Gender Institute's working group to draw up a constitution and academic development plan. This they did by June 1992. The constitution laid out the six principle aims of the Institute:

1) To develop a master's degree and research training in Gender Studies;

2) To foster research, providing a centre for researchers from outside as well as inside LSE;

3) To facilitate interdisciplinary connections;

4) To make academic links within and outside LSE and to make policy links with government, industry and various policy research units in the UK, Europe and beyond;

5) To make known to the community at large the work being carried out in the School and the School's special contribution to this area of academic activity;

6) To establish a basis for future developments in this field.

The constitution also laid out the management structure for the Gl. Responsibility for the overall management of the Institute was to reside with a steering committee. The committee was composed of the director of the Gl, the vice- chair of the academic board, and a ‘representative from each Department of the School with teaching and research interests in the field of Gender Studies (currently, Anthropology, Economics, History, Geography, Government, Industrial Relations, International Relations, Law, Social Psychology, Social Science and Administration, and Sociology.) The representation of Departments on the committee may be varied, as appropriate, in the light of academic developments within the School.’

The membership of the steering committee thus changed from year to year, depending, as the constitution anticipated, on which departments contained faculty with an interest in the field of Gender Studies. So, while it is nearly impossible to record all members of the wider LSE academic community who contributed to the GI's early development, we can identify those scholars whose interest in gender and feminist research led them to take up positions on the Gl Steering committee from 1992 until it was well established in 1995. For a list of the committee members from 1992-95, scroll to the top of this page and look on the righthand side.

Momentum for the Gender Institute at LSE was building. The GI steering committee elected Sylvia Walby to become the first director of the Institute. However, following the offer of a chair at another UK university, Walby resigned her position in March 1993.

Her departure posed some administrative and logistical issues for the fledgling Institute, especially because all those who were involved in the GI still had significant commitments in their home departments. The gender research working group had already submitted to the APRC (Academic Planning and Resources Committee) an academic development plan for the Gl, which now had to be revised. The content of the proposed MSc in Gender Studies would also have to change.

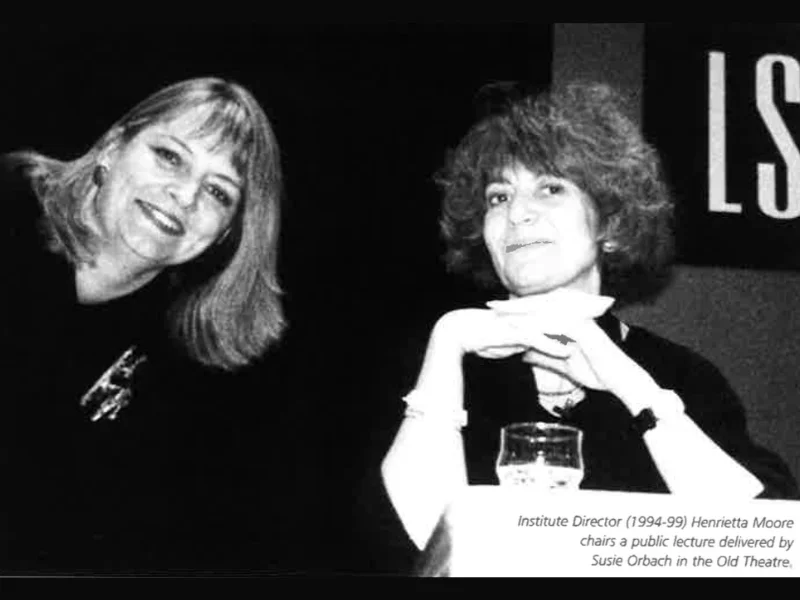

In response, the gender research working group decided to re-structure the administration of the Gl by having a director plus four associate directors, Henrietta Moore stepped forward and agreed to become the director beginning in October 1994, Gail Wilson, Simon Duncan and Sonia Livingstone became associate directors, in charge of the MSc Gender, public lectures and seminars, and research, respectively. Jan Stockdale also joined the Gl at this time as associate director of the European Gender Research Laboratory, the Institute's first major research initiative. This division of responsibility and workload made it possible (at least in theory!) for the new administration to manage their duties in their home departments as well as at the Gl. Derek Diamond became interim-director of the GI for 1993-94. Thus, within three months of Sylvia Walby's resignation, a new administrative structure was in place to take the process forward.

This core group of scholars, together with Hazel Johnstone, formed the GI management committee. They focused their energy in three areas: presenting an overall vision for the development of the GI to LSE and University of London for approval; developing a robust set of research priorities for the GI, and introducing the first postgraduate degree in Gender Studies at LSE. In the revised plan, Diamond affirmed that the ‘essential role of the GI within LSE is to provide a focus and support for the many staff and graduates working on the major intellectual problems posed by the massive contemporary changes in gender relations which form one cutting edge of the social sciences at the turn of the century.’

The GI's status was given a significant boost when Gail Wilson and Jan Stockdale secured the Institute's first major research grant: more than £300,000 from the European Community (as it was then called) in 1993. This grant went towards creating the European Gender Research Laboratory, based at the Gl and headed by Stockdale for the next three years, The Gender Research Laboratory saw a dozen doctoral and post-doctoral scholars take up fellowships within the EC's Human Capital Mobility programme.

Gail Wilson also led efforts to re-draft the plan for the MSc Gender and to secure approval from the University of London. After a period of negotiations between the Gl, LSE and the University of London, the University finally approved the new degree programme in July 1993. That meant there was little time from the moment of approval to recruit students for the next academic year. Nevertheless, the GI launched its first postgraduate degree in Gender Studies in October 1993, with two students signing on.

The MSc Gender was comprised of a core course based in the Gender Institute, plus existing courses focussing on gender concerns scattered around several academic departments. Henrietta Moore devised the MSc’s core course ‘Gender Theories in the Modern World.’18 It drew on the expertise of several LSE scholars as well as visiting lecturers. Like other individuals contributing to the development of the Gl, Sylvia Chant recalls that the indulgence (or, perhaps, forbearance) of scholars’ home departments was key: ‘There were usually just enough of us to supervise an emerging body of PhD students, even if our departments often stressed that this work was "off our own bat" since they were rarely able to get compensation for our time.’

A core group of individuals dedicated themselves to developing the Gender Institute, but getting the GI off the ground was very much a collaborative effort by many parties. The core group consistently made efforts to include the wider academic community at LSE, principally through the steering committee, but also through joint public lectures and seminars. Derek Diamond gives credit to Nancy Cartwright, Fred Halliday and Meghnad Desai — three leading scholars at LSE — who demonstrated strong commitment to the Gl. Professor Cartwright chaired the GI steering committee for three years, and she also secured much-needed office space for several of the HCM fellows. Professor Halliday was an enthusiastic supporter of the GI from the early days. As he recalls:

As far as I know, LSE was the first in the world to put on a postgraduate examined course on gender in international relations. The others had breakfast meetings; we acted! And it was great fun.

And, as we've seen, Professor Lord Desai was using his influence to promote interdisciplinary graduate studies at not one but two new institutes. Successfully establishing the Gender Institute thus required effective teamwork and the establishment of strong links between scholars across departmental and disciplinary barriers.

Henrietta Moore was also one of the GI's most significant advocates and leaders. Formally assuming the post of Director in 1994, she would go on to lead the Gender Institute for five years, In the early days of Moore's directorship (a part-time position), the GI's in-house staff team was small but strong, including Charlotte Martin, as a course tutor, and Hazel Johnstone as the Institute's manager. During this period, Moore and her staff consolidated the teaching programmes and increased student recruitment by drawing on prominent scholars from various departments across the University. Moore identifies her greatest success in these formative years as ‘the very fact of creating the Gender Institute itself, creating an interesting set of research and raising the profile of gender within LSE’.

The Bigger Picture: A Brief History of Gender Studies and Women's Studies

The emergence of the Gender Institute can be situated in the context of the development of Gender Studies and Women's Studies programmes in the UK and abroad in the decades following the Women's Liberation Movement. By the early 1990s, Women's Studies centres and programmes had been developing for at least two decades. Differences may now exist between Women's and Gender Studies programmes in terms of focus, content, teaching approaches and research methodologies.19

However, the emergence of Gender Studies would likely not have been possible, or even imaginable, if not for the ground-breaking work by Women's Studies specialists to develop their field as a legitimate, autonomous and crucial area of research.

Women's Studies emerged as a formal area of study in the United States in the late 1960s. The first course in Women's Studies in the world was taught at the Free University of Seattle in 1965. In 1970, San Diego State College in California became the first to have an officially approved Women's Studies program. In the UK, women involved with the Women’s Movement and leftist politics in the 1960s and 1970s began to set up Women’s Studies courses within higher education and adult education centres. The first course in Britain explicitly called ‘Women's Studies’ was taught by Juliet Mitchell at the Anti-University in 1968. When Women's Studies first emerged in the UK it was geared towards contesting the patriarchal content and assumptions of existing academic disciplines.

As Joanna de Groot and Mary Maynard argue, Women's Studies courses ‘aimed to challenge the silencing, stereotyping, marginalisation, and misrepresentation of women prevalent in historical, social scientific and literary/cultural scholarship’. Such programmes ‘influenced and were informed by the activist agendas of those who, during the 1870s, were involved in political and practical work around "the condition of women" whether on equal pay, anti-woman violence, pornography, childcare issues, or political rights.

The first MA in Women's Studies in the UK opened at the University of Kent in 1980. Gradually, scholars launched other master’s programmes in universities and polytechnics across the UK. By 1988, the Women’s Studies Network (UK) (now the Feminist and Women’s Studies Association (UK and Ireland) had been formed as the national subject association for the discipline. Universities in Latin America launched Women's and Gender Studies degrees in the mid-1980s, followed a few years later by African and Asian universities. At the beginning of the 1990s, courses with the disciplinary label ‘Gender Studies’ began to open at universities in the UK, such as at the Universities of Hull and Humberside, as well as in North America. Such programmes aimed to study gender as a structuring tenet of society, from an interdisciplinary perspective.

By the early 1990s, despite ‘Thatcherism’ and academic antipathy to feminism as well as various institutional constraints (which would continue into the 1990s and beyond, as will be discussed), Women's and Gender Studies programmes, conferences, networks, research and publishing industries were flourishing. Women’s and Gender Studies departments across the board were increasing student recruitment and developing new programmes and degrees. The first single honours undergraduate Women's Studies degrees in the UK were launched in this decade, at (the then) Polytechnique of East London, Lancaster University and Roehampton Institute, London. In 1993, the international Handbook of Women's Studies listed 74 Women’s and Gender Studies courses in the UK, 47 or which were full Women's or Gender Studies degrees, either at the Diploma, undergraduate or postgraduate level. Furthermore, with the ‘enormous growth of feminist research inside and outside the academy’ in the 1990s, disciplines such as Sociology, History and Literature were ‘also in the process of being transformed as a result of the debates and ideas coming from within Women's Studies’.