Proxies: what can we learn from the stand-ins that are helping to shape real life?

Contents

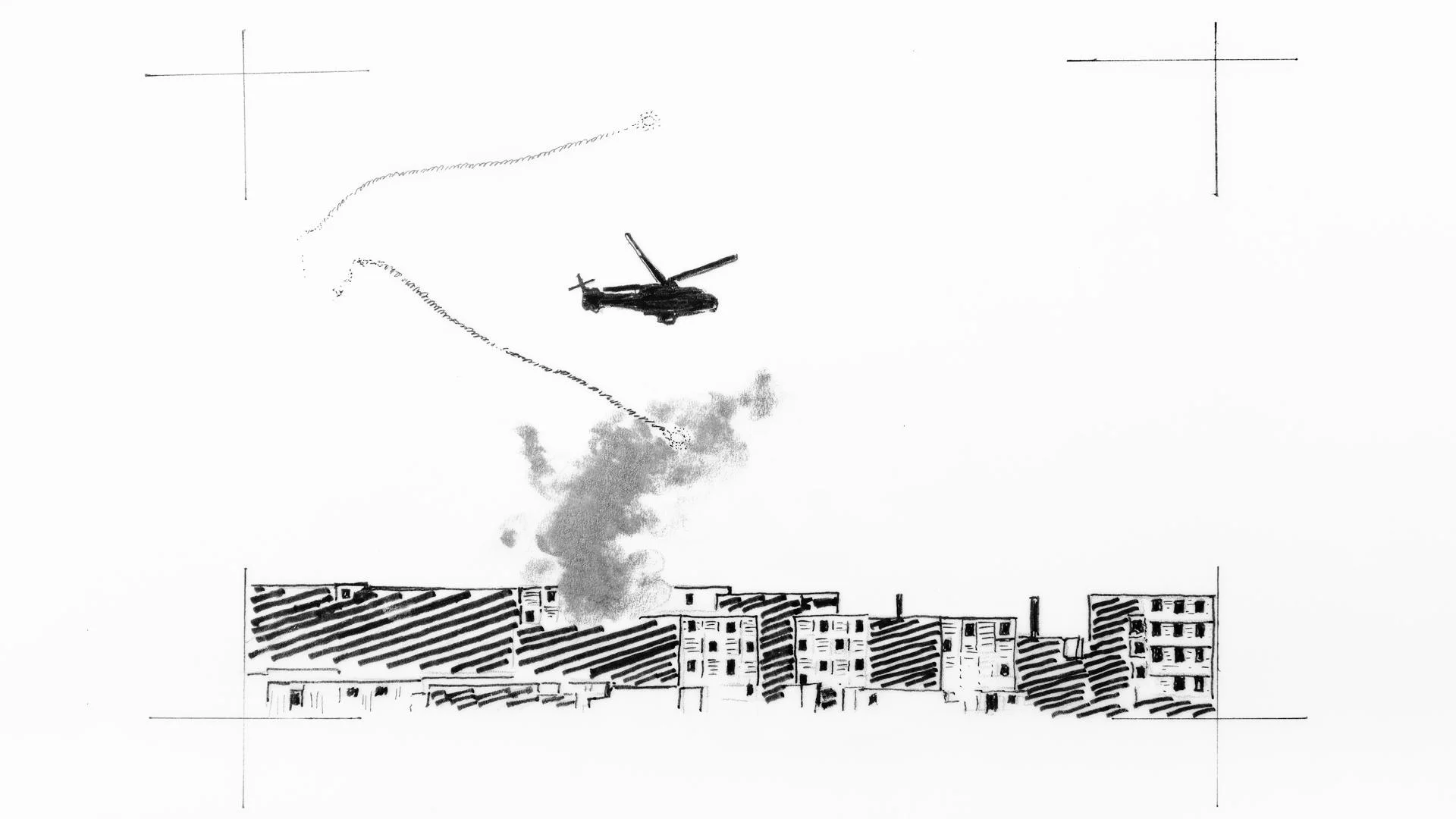

In the southwest of Arizona, near Yuma, you can find a small town called "Yodaville". With a town centre, and eight radiating boulevards, it stands in stark contrast against the surrounding desert. Yodaville is empty - in fact, it’s never been lived in - because Yodaville is a "test city" or, to put it in the terms of the US military, who own and operate the town, Yodaville is an "Urban Target Complex".

Chances are you’ve never heard of Yodaville, which was built in response to American military deaths in the Battle of Mogadishu (the events, you might recall, from the film Black Hawk Down). Believing that their training was overly reliant on mock cities that looked too European they built Yodaville in the '90s. It was designed, in the loaded terminology of one RAND Corporation (an American non-profit global policy think tank) report, to reflect the "chaotic environments found in densely populated areas of the developing world".

Yodaville is a kind of proxy city for the world "out there". When the American military saw the edges of its empire strained by war in unfamiliar territory, they decided they needed a proxy for the kind of places they would be going to war in the future. Sure enough, when they went to war in Iraq and Afghanistan, one Colonel put it bluntly: "If a pilot can drop a bomb and hit a target in Yuma, he can drop a bomb and hit a target in Iraq... They got heat. We got heat... It is the ideal place to train."

Proxies might be necessary, but how we choose and design them can come at a great cost to society.

From calculating inflation to showing what the perfect pasta serving looks like, proxies help us in all sorts of ways

In my new book, Proxies: the cultural work of standing in, I examine the history of proxies like Yodaville - the people, places, and things we choose to stand in for the world. Maybe you’ve never thought about all the proxies around you, but when you start to notice them, you’ll see them everywhere.

Want to calculate inflation? We use a market basket of goods - including stuff like cereal and juice - to track the average cost of living. Do you want to know if your tagliatelle meets the exacting standards of the Bologna Chamber of Commerce? You’re in luck because the Chamber has a "Golden Tagliatella" on display, which you can make sure meets the exact measurements to officially qualify (8mm when cooked). Let’s stick with food. The National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland, will sell you a $700 jar of peanut butter to act as a reference standard.

Averages, ideals, and references: this is the world of proxies. Of course, we also have proxy votes, proxy servers, and proxy wars. A world of things, places, and people, who can officially or unofficially stand in for the real thing. In the 19th century, here in the UK, the imagined "reasonable person" by which we judge all sorts of legal matters, came to be known as the "Man on the Clapham Omnibus" because it was imagined that he (a commuting suburbanite) would be a good proxy for reasonableness. Suddenly an abstract idea had become something real: a man, on a bus, in Clapham.

The shape, texture, and look of proxies can radically change how systems and technologies work.

When "average" means pale-skinned – the link between proxies and inequity

Of course, it’s not all noodles, spreads, and omnibuses and some proxies matter more than others. Just as Yodaville was constructed to hone the American military’s approach to warfare, the shape, texture, and look of proxies can radically change how systems and technologies work. In Proxies, I examine how test images dating back to the mid-20th century have been shaped by an emphasis on pale skin. I tell this history by following the "Lena" or "Lenna" image, from its earliest days at the University of California, to its ascent as an icon for digital imaging, as a field and a profession. The Lena image is a well-entrenched proxy, but it’s also a cropped excerpt from the centrefold image of the November 1972 issue of Playboy Magazine. As such, it has also become a proxy for the gendered mistreatment and exploitation of women in technical industries. Tracing its history shows us how stand-ins can also be crystallisations of the cultural and social conflicts underlying our infrastructures.

The whiteness of test images, used to calibrate media and train software, is a legacy with consequences we still see today when facial recognition algorithms, test proctoring software, and the basic architecture of our contemporary visual culture regularly fails to recognise or register large swaths of people. Recently, researchers have shown that self-driving cars show a "predictive inequity" in detecting pedestrians of varying skin tones and that pulse oximeters—which provide vital information about a person’s pulse and blood-oxygen levels—provide less accurate readings for people with darker skin. Often we can trace these inequities and failures to bad training data, or to a misbegotten vision for the world "out there." In other words, there is always a politics to proxies.

I explore this through the history of the standardised patient programme, where actors play act as ill or disabled to help train physicians in clinical skills and bedside manner. But, I ask, what are the consequences of building empathy through this kind of simulation? Such a process can, I argue, turn pain and illness into a kind of masquerade and disconnect it from the lived realities of real people with real bodies. Proxies might be necessary, but how we choose and design them can come at a great cost to society.

We can't get rid of proxies, but we should pay them more attention

Ultimately, our world is shaped by the things, places, and people we use to test, train, and calibrate our complex systems. The problem is, we need proxies. As silly as it might sound, the health and safety of our food is guaranteed by things like a reference jar of peanut butter that manufacturers can use to compare their own peanut butters. But the choice of this jar over that one, or this test image over another, can have long-lasting and unpredictable consequences for the people who have to live within rules, standards, and infrastructures not of their own choosing.

Image: "Lenna image processing 5" by sp2mi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Download a PDF version of this article