How can offender rehabilitation help address prison overcrowding?

Contents

In a recent speech given at His Majesty’s Prison Five Wells, the new Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice warned of an imminent "collapse of the British criminal justice system" unless swift action was taken to ease the pressure in overcrowded prisons. Just over one month later, the UK government enacted emergency measures as a result of prison overcrowding.

"Operation Early Dawn" will see more prisoners remain in police cells until prison space becomes available. But could there be a more effective approach? According to Dr Johann Koehler, an expert in criminology and Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Policy at LSE, because almost 80 per cent of offenders have previous cautions or convictions, an emphasis on offender rehabilitation could be a more impactful way of alleviating pressures on the system.

He explains: "If you provide suitable intervention and support for people who are undergoing certain kinds of criminal justice sentence, then the evidence is clear that you can quite dramatically improve chances of stemming future reoffending and reducing prison populations."

The government’s immediate approach prioritises a community-based framework for delivering criminal justice. For now, that priority entails reducing prison time for qualifying offenders from the current 50 per cent to 40 per cent, so that they spend the remainder of their sentences under probation in community settings.

Dr Koehler sets out that there are trade-offs for prioritising community-based offender rehabilitation as opposed to rehabilitating people in a prison setting. "Both environments include political and practical compromises," he notes, "and policymakers must think carefully about how to weigh them alongside one another."

Even if some people do exceedingly well [in community-based rehabilitation], those good outcomes rarely spread across the board.

Does it matter whether offender rehabilitation takes place in the community or in custody?

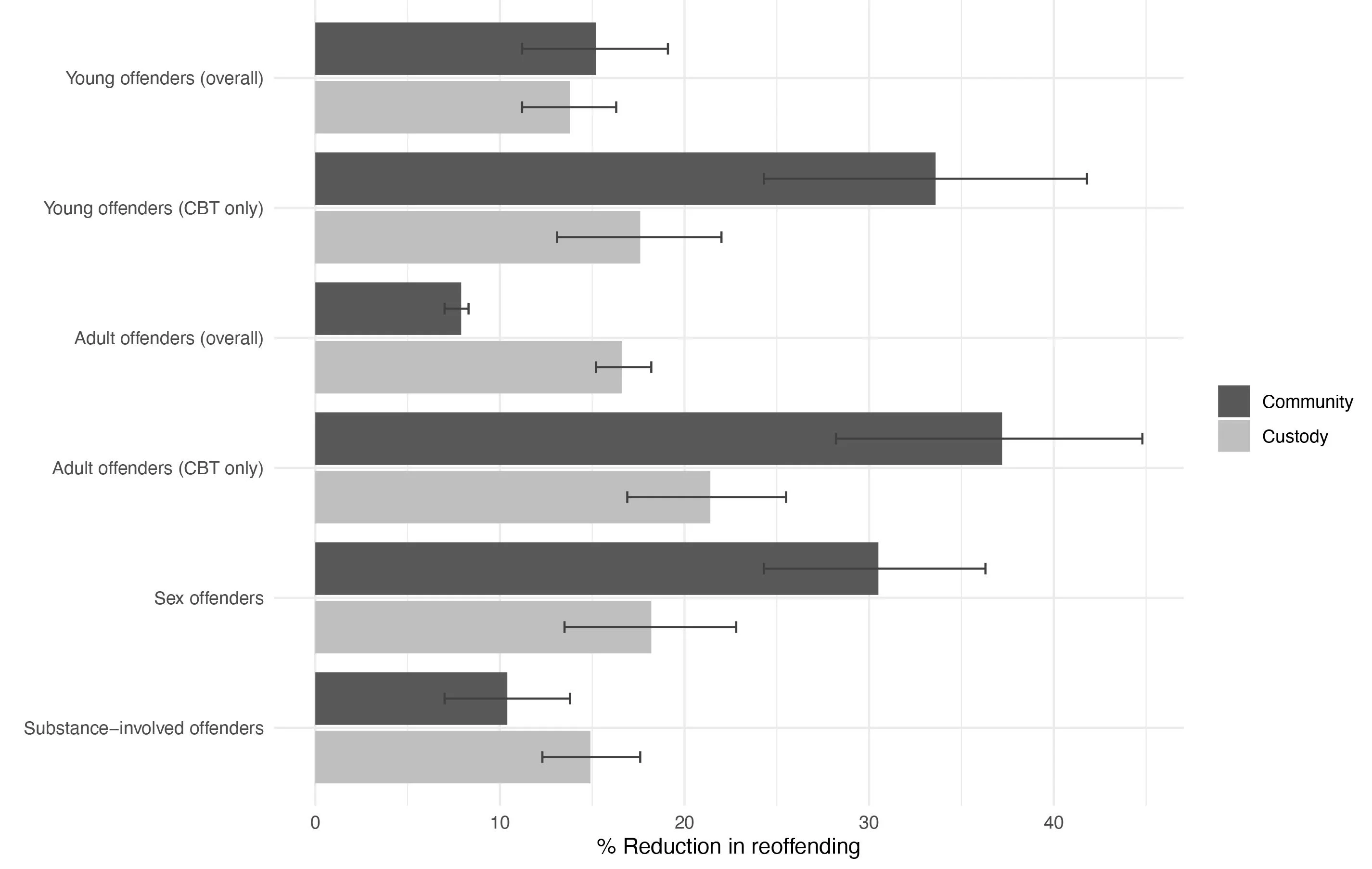

In a comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of correctional treatments, Dr Koehler and Professor Friedrich Lösel of Cambridge University and the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg synthesised 53 analyses of rehabilitation’s effects on reoffending. They find that offender rehabilitation can, on average, yield sizeable reductions in reoffending. They also find noteworthy variations depending on whether correctional treatment is delivered in the community or in custody.

On the one hand, community-based treatments deliver impressive results on average. A less restrictive environment affords leeway and flexibility to deliver interventions tailored to individual needs and local circumstances. But flexibility’s benefits may also have costs. The effects of community-based treatments on reoffending tend to be more unpredictable than treatments delivered in custody. Dr Koehler confirms, "even if some people do exceedingly well, those good outcomes rarely spread across the board."

On the other hand, although custodial interventions reduce reoffending on average, the improvements are more modest. In a restrictive setting, correctional interventions are more likely to converge on a one-size-fits-all approach that lacks personal responsiveness. But that inflexibility may also have benefits. The ability to supervise people in custody, and to monitor treatment delivery, provides policymakers with the benefit of more predictable outcomes.

Dr Koehler explains the trade-off from the policymaker’s point of view: "In conditions where we know we need to drastically reduce reoffending, it could be tempting to take the option that promises the most impressive headline figures. But important policy priorities might mean that — for purposes of planning and budgeting, as well as delivering on promises to the public — there is real value for policymakers in being able to forecast outcomes reliably and consistently."

For this reason, Dr Koehler explains, policymakers must judge difficult political trade-offs: "The new Labour government has expressed an intention to prioritise community-based criminal justice. Sound ethical and practical considerations may well support that wisdom, but policymakers must also account for the outcomes that are likely to follow when weighing that priority’s benefits and costs."

Unlike the outcomes we see among other groups, people with substance involvement problems show greater reductions in reoffending when they undergo treatment in a prison.

Rethinking rehabilitation

In their research, Dr Koehler and Professor Lösel also compared outcomes across different groups of people who underwent correctional treatment. The results of those comparisons raise challenging policy questions: "For example," Dr Koehler shared, "unlike the outcomes we see among other groups, people with substance involvement problems show greater reductions in reoffending when they undergo treatment in a prison. What are policymakers to make of that? How should we understand the dramatic improvements that follow when people convicted of sex offences receive treatment in the community? And how might these results figure in future policy reforms?"

Dr Koehler is optimistic about the justice reform work that lies ahead: "Right now, we're having serious conversations about criminal justice generally, and about prisons and probation specifically. Those conversations reflect a readiness to shape criminal justice so that it can be more effective, sustainable and humane. I think rehabilitation can play a prominent role in that future." If these conversations lead to an increased focus on prisoner rehabilitation, Dr Koehler is hopeful this could help reduce the dangers of prison overcrowding that many in UK prisons are experiencing today.

Dr Johann Koehler was speaking to Molly Rhead, Media Relations Officer at LSE.

Download a PDF version of this article