Ensuring Universal Health Coverage (UHC)—that everyone around the world has access to an adequate package of needed health services of sufficient quality at bearable cost—is one of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and is an aim of health policy in many countries. But UHC is costly, and consequently, countries face difficult decisions on how to fund it. How can such decisions be made in an equitable manner? In this blog post, Alex Voorhoeve answers this question.

Decisions about how to finance Universal Health Coverage—how to raise, pool, and spend money for this purpose—involve two aspects of fairness. Substantive fairness is equity in who gets what and who pays for it. Procedural fairness, in contrast, is equity in how decisions are made: whether people’s views are sought and considered, whether their interests are weighed impartially, and whether public justifications are provided for decisions. Substantive fairness has long been recognized as key to decision-making on the path to UHC and prominent attempts have been made by international organisations to advance practical criteria of substantive fairness. In contrast, procedural fairness in health financing has occupied less attention. There have, of course, been important attempts by scholars to develop conceptions of procedural fairness in coverage decisions—most notably, Norman Daniels’ and James Sabin’s Accountability for Reasonableness. However, their framework assigns little significance to public participation. Moreover, it focuses on only on which services to purchase; it is silent on the other aspects of health financing, namely raising money through taxes or insurance contributions and pooling funds (that is, gathering money in one or more “pots” to serve a population’s needs).

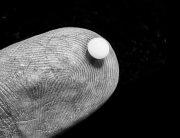

Against this background, the World Bank, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and the Bergen Center for Ethics and Priority Setting tasked a team of researchers with developing a comprehensive understanding of procedural fairness in health financing. The team, of which I was a part, wrote a report which has been published by the World Bank and is the topic of a special issue of Health Policy and Planning and a number of responses that criticize, deepen, and extend its ideas in Health Economics, Policy and Law. This blog post explains the understanding of procedural fairness the team developed, which is visualised in Figure 1.

Foundational principles of procedural fairness

At the heart of our framework are three foundational principles. (I) Equality calls for equal access to relevant information, equal capacity for participants to express their views, and an equal opportunity to impact decisions, regardless of factors that often create disparities in influence, such as social and economic status, health, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and religious affiliation. It also requires that people’s views are treated with respect, that is, taken seriously and assessed on their merits. (II) Impartiality requires that decision processes are unbiased and that those with a personal interest in the decision do not unduly influence it. (III) Consistency over time demands steadiness in procedures by which decisions are made, so that like cases are treated alike, and people can form reasonable expectations about how the decision system will operate.

Figure 1: A framework for procedural fairness (World Bank, 2023, p. 10).

Practical criteria for procedural fairness

These principles motivate seven practical criteria for procedural fairness, which we group into three domains. The information domain encompasses three criteria. (i) Reason-giving, at its most demanding, requires a dialogic process in which all stakeholders can explain why they favour or oppose a policy, evaluate each other’s reasons, and freely revise their views in the light of this exchange in a rational way. But such back-and-forth may be unfeasible or too costly; is can also be unsuited to decisions that primarily involve the application of expert knowledge. In those cases, reason-giving may take a more limited, monological form in which decision-makers simply offer public justifications for their decisions. (ii) Transparency requires that important information is provided about the decision process and about what has been decided and for which reasons. It also requires that information be made available about whether agreed policies have been carried out and what their effects have been. (iii) Accuracy and completeness of information demands that the decision-makers seek out a range of evidence and opinion and assess it for correctness.

The voice domain encompasses two criteria. (iv) Participation concerns the extent to which interested parties and the public (or their representatives) can acquire and use pertinent information, communicate opinions, and play a role in the decision process. (v) Inclusiveness demands that governments ensure that all people, especially those who are typically marginalised, can join in, so that the full range of perspectives is considered and everyone’s interests are taken into account.

The oversight domain also contains two criteria. (vi) Revisability requires that there are routes through which decisions can be reconsidered when weighty reasons are offered for doing so. (vii) Enforcement calls for structures that ensure all criteria are followed and that provide assurance that decisions are carried out.

In sum, to be fair, decision systems for health financing must be open and inclusive. This requires that a comprehensive range of evidence and viewpoints are sought and considered, that citizens’ interests are weighed equally, and that reasons for policies are publicly debated. It also requires that these attributes of decision-making are formalised rather than reliant on policy-makers’ good will. Procedural fairness, so conceived, is a demanding ideal. But like its cousin, substantive fairness, it is a matter of degree. In our research, we find that improvements along its various dimensions are possible in countries at vastly different income levels and even in places without a well-functioning democracy. Securing such improvements may, of course, be costly. To know whether it is worth it, we need to understand the value of procedural fairness; that is what we will discuss in the next blog article.

By Alex Voorhoeve

Alex Voorhoeve is Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the LSE. He works on the theory and practice of distributive and procedural justice (especially as it relates to health), on rational choice theory, moral psychology, and Epicureanism. He has acted as a consultant on justice in health to the World Health Organization, the World Bank, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and is a member of the Bank of England’s and UK Treasury’s Academic Advisory Group on the development of a “digital pound”.

Connect with us

Facebook

Twitter

Youtube

Flickr