We have reached part three of our Taylor Swift blog series. Our series highlights several chapters of the recently published book ‘Taylor Swift and Philosophy: Essays from the Tortured Philosophers Department’ by Catherine M. Robb and Georgie Mills and builds up to our anticipated ‘Taylor Swift and philosophy’ public lecture at LSE. This week’s article was written by LSE Philosophy Professor Jonathan Birch, who explores how Taylor Swift is dealing with grief in her work.

Grief and Memory

In “marjorie,” Swift reflects on what, if anything, of our loved ones survives death. The song is about Swift’s maternal grandmother, Marjorie Finlay, a singer who often performed in opera and with symphony orchestras. Details of Marjorie’s life are scarce. Her Wikipedia page relies heavily on a few newspaper clippings that briefly mention a childhood in St Charles, Missouri, followed by marriage, then moving with her husband’s career to Havana, Caracas, and Puerto Rico, where she had her own TV show for a time. These cannot have been ideal conditions to pursue stardom. Those frequent moves cannot have left much time to forge a career in any single place, and they took Marjorie far away from the major centers of gravity in the music industry. Swift alludes in the song to Marjorie’s “closets of backlogged dreams.”

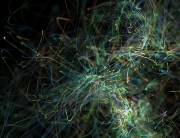

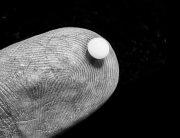

A photograph of Marjorie Finlay (née Moehlenkamp) from The Lindenwood Colleges Bulletin, June 1949. (Credit: Public domain)

Marjorie died in 2003. What remains of Marjorie after her death? A disordered set of memories. In the verses, Swift relates some pieces of advice inherited from her grandmother. When Taylor calls the advice to mind, she thinks “if I didn’t know better, I’d think you were talking to me now. What died didn’t stay dead: you’re alive, so alive.” Some other fragments rise to the surface in the song’s bridge, which describes “long limbs and frozen swims—you’d always go past where our feet could touch.”

Part of what makes the song so poignant is that these scattered and partial memories are tinged with regret. Swift was not as close to her grandmother as she now wishes she had been. The memories don’t form a complete or coherent picture. A little selfishly, she wishes Marjorie had imparted more advice on how to live. But there is more to it than that: Swift also longs for physical contact, material continuity, evidence that Marjorie existed. The line where Swift laments that she “should have kept every grocery store receipt” hits particularly hard.

The song ends on an ambiguous note: “I know better, but I still feel you all around. I know better, but you’re still around.” Swift acknowledges that the idea of a person literally surviving by means of a patchwork of memories and snippets of advice is fanciful. It feels as though they are still there, that’s all. But she also reminds us that, through curating these personal memories, she is securing a legacy for her grandmother, granting her an enduring place in our shared cultural memory.

Swift’s lyrics fit well with ideas put forward by Michael Cholbi in his excellent book, Grief: A Philosophical Guide. Cholbi’s powerful insight is that grieving is a process that transforms, but does not end, our relationship with the deceased. When someone dies, our relationship with them is not simply terminated: just as we continue to be related to people who are separated from us in space, we continue to be related to people who are separated from us in time. The past is real and we are related to it, but the nature of the relationship changes fundamentally. This process of transformation is exactly what “marjorie” describes.

Memory and Transformation

What is the nature of this transformation? When we grieve a person’s death, it is because we had a significant relationship to that person: a relationship that mattered. That relationship can take many forms, and it need not be a close family relationship or friendship (for example, relationships of rivalry, collegiality, or fandom can also lead to grief). But the depth of our grief is related, Cholbi suggests, to how central the deceased person was to our practical identity: our sense of who we are, as it arises in the context of making decisions and choices.

Your practical identity has many aspects: you may think of yourself as a popstar, singer-songwriter, film director, daughter, granddaughter, and more. None of these would apply to me, but I have my own list: lecturer, scholar, policy advisor, mentor, father, husband, brother, son, and so on. We can all think of a list like this. When I make decisions, I try to be true to these aspects of myself and the expectations and commitments they bring, and which aspects matter most will depend on the context.

Any aspect of my practical identity can be rocked by the loss of the people who help me sustain that aspect. In 2007, I grieved the loss of my first academic supervisor, Peter Lipton, even though I never really knew him as a friend—and I think that was because my initial identity as a scholar of philosophy was built around my relationship to him. Grief can strike us gently or severely, depending on how much a person mattered to our identity, and why. Grief hits us hardest of all when a central plank of our practical identity falls away. We lose our sense of who we are and how to live. This is often, but not always, associated with losing a relative or friend.

The process of grieving is one of trying to rebuild that practical identity as best we can. This helps explain why grief takes as long as it does, and why the process is so variable from one person to the next. Some rebuild fast, whereas for others the experience is long and slow, often characterized by ups and downs as early attempts unravel. Sadly, some people succumb to grief, never succeeding in rebuilding a practical identity.

When we think about grief in this way, it becomes clear that “marjorie” describes a late stage in the process of grief. We might even call it a “post-grief” song, because it captures Swift’s relationship to Marjorie many years after the process of transformation triggered by her death.

And the song aptly illustrates Cholbi’s point: it is not that Swift no longer has any significant relationship to Marjorie, and it is not as though Marjorie has dropped out completely from Swift’s practical identity. Rather, the nature of the relationship is transformed. Marjorie continues to be a source of advice, though the advice now comes in the form of remembered maxims, not actual conversations. Swift cannot turn to Marjorie with new problems, but can take the advice she offered at a general level (“Never be so polite you forget your power…”) and apply it to her current situation.

Marjorie also features in the way Swift conceptualizes her plans and goals. Indeed, securing a legacy for Marjorie now features among those goals—a common way in which those we have lost continue to shape our choices, though certainly not the only way. By performing the song on the “Eras Tour” (even though it is not, musically, a natural choice for a stadium tour), Swift demonstrates Marjorie’s continuing relevance to her life. Moreover, Swift’s goals include fulfilling the “backlogged dreams” (presumably, of stardom) that went unfulfilled in Marjorie’s case, and that Swift sees herself as having inherited.

We see in this song the result of a successful grief process, and we can learn something from this about the value of grief. People often reflect that, although grief is one of the worst forms of suffering in the moment, they would not take an “anti-grief pill” that completely destroyed it. It feels like something important, something valuable. Cholbi proposes that the value consists in the self-knowledge—the knowledge of who we are—that grief brings. Through grieving, we can learn about the significance of our relationship to the deceased. We can learn why they mattered to us—and (often) why they mattered so much more than we thought they did. We learn about how our practical identity is structured, who it depends upon, and why. This knowledge helps us to live better from there on.

“Marjorie” exemplifies this achievement, demonstrating how Swift has recognized and preserved the significance of Marjorie to her practical identity. If Swift had taken an “anti-grief pill” in 2003, she might never have achieved the self-knowledge about Marjorie’s significance to her own life and identity that the song beautifully crystallizes.

There are several points of convergence, then, between Swift’s songwriting and Cholbi’s philosophy of grief. Both highlight our continuing but transformed relationship to those we have lost, grief as a process of reconstruction, and the value of grief in promoting self-knowledge. Is it more than just convergence—does Swift add something new?

I think something important is added by the mode of expression. Critics of Cholbi have argued there is something problematically self-centred about this way of thinking about grief—a way that brings it back to you and your practical identity. Should grief not centre the person you have lost? One reply is that when we successfully grieve we centre the person we have lost by reconstructing our own practical identity in a way that preserves their significance to us. But merely saying this will not persuade a critic that it can really happen. Swift’s song shows it.

By Jonathan Birch

Jonathan Birch is a Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at LSE, specialising in the philosophy of the biological sciences. He is working on evolution of social behaviour, the evolution of norms, animal sentience, and the relation between sentience and welfare.

On Monday 28 October, LSE Philosophy is hosting the public lecture ‘Taylor Swift and philosophy’ with Eline Kuipers (Ruhr University Bochum), King-Ho Leung (King’s College London), Georgie Mills (Tilburg University), Catherine M Robb (Tilburg University) and Jonathan Birch (LSE Philosophy). The event is free and open to all. You can attend in-person or online. More information about the event.

Connect with us

Facebook

Twitter

Youtube

Flickr