Many researchers now agree that animal consciousness is more common than once believed. One of the leading animal sentience researchers is LSE Philosophy Professor Jonathan Birch. His research is often met with scepticism from inside and outside the Philosophy world. However, he sometimes is a reasonable sceptic himself. In our latest blog post, Jonathan Birch gives insights into his inner dialogue with his own sceptic.

The idea that many other animals have conscious experiences, including all vertebrates and many invertebrates, is far less controversial in science than it used to be. In truth, I’m not sure it was ever all that controversial in the rest of society. In my experience, people do not seriously doubt the sentience of their pets, whether the pet in question is a dog, cat, iguana, fish, or tarantula. On this issue, scientific opinion seems to be moving into closer alignment with popular sentiment. In April I co-organized the New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, a public statement signed by 290 scientists and philosophers that aimed to capture this sea change in scientific attitudes.

Yet there are still many sceptics out there. Some are actually existing people in my emails and DMs. Others are ghosts from the past, like René Descartes, who wrote that “language is the only certain sign of thought hidden in a body” and arch-behaviourist John B. Watson, who wrote that “one can assume either the presence or the absence of consciousness anywhere … without affecting the problems of behavior by one jot or one tittle“. Their arguments shaped the scientific culture of their time, and for generations thereafter, and their imprint can still be felt strongly.

It can be tempting to accuse sceptics of motivated reasoning. The enthusiasm of both Descartes and Watson for vivisection is well known. Some of today’s sceptics about fish sentience are financially dependent on the aquaculture industry. But it just isn’t true that all sceptics stand to benefit commercially or professionally from their scepticism. I know a number of reasonable sceptics—in fact, I am a reasonable sceptic too. I constantly have inner dialogues in which I try to make the sceptical case as sincerely and honestly as I can in order to assess how strong it really is.

I want to put that inner dialogue out in the open. I’ve framed it as a dialogue between two characters: JB, an enthusiastic supporter of the emerging science of animal consciousness, and IC, his inner critic.

JB: We should start with the question: what entitles me to infer that the people around me have conscious minds? It is an “inference to the best explanation” or “abductive” inference, a completely mundane kind of inference found in all areas of science.

I have a lot of behavioural data that needs explaining, after all. I am constantly having conversations with other people about my experiences and theirs, about our shared experiences, about patterns of similarities and difference. I ask them how they felt when that goal was scored, whether they are feeling more tired or energetic than they were yesterday, whether that painting evokes the same mood in them as it does in me.

It could be that, although I am having experiences, I live in a world of philosophical zombies who are knowingly faking all these reports. It could also be that, while they are not knowingly deceiving me, other people use all the same words to refer to internal computations that feel like nothing to them, and this vast difference in our inner lives never comes to light. A third explanation is that we do, in fact, have conscious experiences of quite similar kinds, allowing us to convey truths to each other about how we feel.

How can we choose between these explanations? The first two are desperate and weird, positing a metaphysical gulf between me and the people around me for which I have no evidence or explanation. By contrast, the third one explains everything very simply and straightforwardly, meshing well with everything else I believe, positing no weird gulfs, and so it is reasonable for me to believe the third one.

Now let us turn to other animals. What entitles me to infer that they have conscious minds? Exactly the same type of inference! Here too I have a lot of behavioural data in need of explanation. For pet owners, the data are especially rich, which may explain why they are so confident.

It’s true that linguistic evidence is generally absent (though other forms of communication may be relevant). But linguistic evidence, though a good and important kind of evidence in the human case, was never the only relevant evidence. When I interact with preverbal children, I’m again in a situation where by far the best explanation for the data is that we are both conscious beings. The idea that the child laughs and cries at amusements and threats unconsciously seen, zombie-like, puts us back in “weird gulf” territory. This is nowhere near as good as the explanation that posits conscious experiences of similar kinds in both of us.

Why is the situation any different when we interact with a dog? The dog’s “excitement-like behaviour” when chasing a ball is very well explained by positing a feeling of excitement, and very much less well explained by some kind of unconscious analogue of excitement—it’s that weird gulf again, where there is absolutely no reason to posit such a gulf.

IC: I won’t try your patience with a long discussion of anthropomorphism. Obviously, we are very prone to “see” mentality in systems that don’t have it but that mimic human features, like humanoid robots and animated characters. That always hovers in the background as an alternative explanation for why pet owners feel so sure (granted, one that works better for dogs than for tarantulas). But I won’t blather on about this because it only becomes relevant, really, if there is something wrong with the abductive inference you’re defending.

I see it like this: there are standards of inference for everyday life, and there are other, higher standards that apply in science. The “inference to the best explanation” appears in both settings, but it’s a huge mistake to assume that the standards are the same in each case.

In everyday life, we can be fairly relaxed about explanations that posit causes just to explain something that needs explaining. I see oddly-shaped footprints in the snow, so I infer a person with shoes of that shape walked that way, even though I have no other evidence of such a person existing—that’s fine in everyday life. But in science we can’t allow that kind of thing or we’ll face an explosion of convenient causes. You can’t posit a new particle solely to explain a single anomalous track in the cloud chamber. Positing new particles has to obey constraints imposed by other evidence and by theories. More generally, there are strict entry criteria for what counts as an eligible causal explanation of a phenomenon in science.

What are the entry criteria? John Herschel’s “vera causa” standard has been influential (famously, it influenced Darwin). Herschel argued that, in science, explanations must cite causes whose existence and competence to produce the phenomenon of interest has been independently established. Darwin took this maxim extremely seriously, arguing via a detailed analysis of selective breeding that unconscious forms of selection exist and are competent to produce large changes. Only then could he appeal to this independently established “vera causa” to explain diversity and adaptation in the natural world.

Now, here is the basic problem: conscious states don’t meet the vera causa standard. You posit them to explain the behaviour we see in other animals—OK, but you haven’t independently established their existence and competence to produce that behaviour.

To make matters worse, there are deep reasons why no one can do this. Firstly, the very existence of these states is called into doubt by “illusionism” about consciousness, a la Dan Dennett and Keith Frankish, and in older literature by “eliminative materialism” (e.g. the Churchlands, Richard Rorty, Paul Feyerabend). Secondly, their competence is called into doubt by the possibility of epiphenomenalism, a la T. H. Huxley: the idea that conscious experience might be a sideshow with no effect on behaviour, akin to the steam that trails behind a steam train making no difference to the workings of the engine. There are also theories that we might call “near-epiphenomenalist”, in that they give consciousness only very small and circumscribed causal roles, e.g. they say that experiences cause reports of experience, but no other behaviours.

To establish the existence and competence of conscious mental states to explain observations of animal behaviour, you’d first have to refute illusionism, epiphenomenalism, and near-epiphenomenalism, and you can’t do that—these are all live options. As long as that’s the case, conscious mental states will never meet the vera causa standard.

JB: I suspect the big disagreement between us concerns the relevance of first-person evidence. I think first-person evidence completely smashes a strong form of illusionism that denies there is anything it feels like to be me. It leaves room for weaker forms that deny some specific theoretical posit (like “qualia” or “phenomenal properties”, understood in some theoretically-loaded way), but that’s alright—materialism has always involved a large element of this.

More contentiously (and there is a group of critics who will be with me on the above but will get out now) I think first-person evidence establishes the centrality of conscious experience to human mental lives, including its causal efficacy, especially in the areas of learning and decision-making. The “steam” view of conscious experience just isn’t viable. I know that I went to the Musée D’Orsay in April of this year because I enjoyed a visit last year. It wasn’t some unconscious process occurring simultaneously with my enjoyment that influenced my decision—it was the enjoyment. One can debate the coherence of epiphenomenalism in the seminar room (and I think it is, in fact, coherent) but there’s no reason to take it seriously as a theory of consciousness, because first-person evidence destroys it.

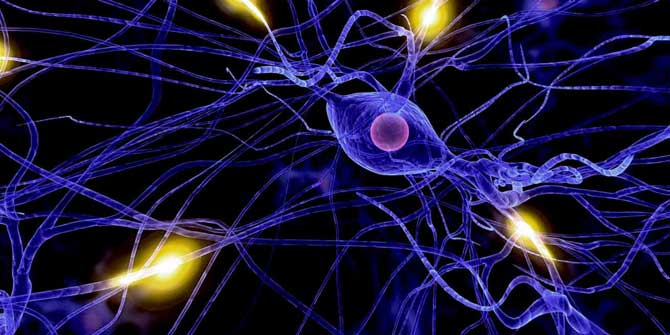

Even more contentiously, I think first-person evidence takes out near-epiphenomenalism too. Conscious experience is not peripheral to my mental life, barely doing anything—it’s at the heart of how I learn about the world, how I value possible futures, and how I make big-picture, strategic decisions about the shape of my life. That basic insight is our way in to studying consciousness scientifically in other animals. We can study their learning and their decision-making, and we can look for the neurobiological and cognitive mechanisms that sit at the centre of their mental and evaluative lives and compare them across taxa.

IC: Right, so your position is that first-person evidence sufficiently establishes the existence and competence of conscious experience, so that we don’t need independent evidence of these things before we start positing conscious states to explain the behaviour of other animals. Got it. You can guess what I will say in reply—that a total ban on “first-person evidence” is another very important scientific norm, especially in psychology. This was the grain of truth in behaviourism. Watson saw how the psychology of his time overly relied on introspection—saw how it was putting an air brake on progress—and he offered an alternative vision in which first-person data had no role.

I see Dennett, in Consciousness Explained, as trying to do for consciousness science what Watson did for psychology. He saw two futures for the field. In one, first-person evidence is taken seriously as evidence and the field goes nowhere. In the second, first-person evidence is ruled inadmissible at the outset, and we take people’s public reports of conscious experience not at face value (as accurate descriptions of their inner lives) but rather as our explanatory target, using the standard methods of cognitive neuroscience to investigate the processes that lead people to make these reports—an approach he called “heterophenomenology”.

If we take Dennett’s path, we have no right to go around positing real conscious states to explain animal behaviour. At the start of inquiry, the only evidence that these states even exist or do anything is inadmissible first-person evidence. It’s likely that, by applying the heterophenomenological method, we will ultimately discover real neurobiological mechanisms that can explain a lot more about a person than just their reports of phenomenology (e.g. the “global neuronal workspace” may be a good example of this—Dennett was a fan). At this point, we will be able to turn back to other animals. But then the right question to ask is: Do other animals have versions of these mechanisms? Not: Do they have conscious experiences? The latter question simply never arises. By the time we know enough about humans to justify turning our attention to other animals, we also know enough to replace “conscious experience” with more legitimate neuroscientific categories.

JB: Thanks for the Dennett exegesis. Look, I think this is a respectable kind of scepticism—a scepticism that rests on (a) tough entry criteria for causes that can feature in scientific explanations, plus (b) a ban on first-person evidence, leading to the conclusion that (c) conscious mental states don’t meet the entry criteria. We see a huge divide in consciousness science over point (b), and debates about animal consciousness can be seen as a key flashpoint within that conflict. None of this stops a respectable sceptic from making everyday inferences—and believing, like everyone else, that their pets are conscious.

But in the fundamental dispute over (b), I’ve changed sides over the years. I think at one time I would have agreed that first-person evidence has no place in science. I now see this as an impoverishing move, a throwing away of valuable evidence. We should be very cautious in trusting the deliverances of introspection, of course, but that doesn’t mean they can’t provide initial, tentative, defeasible evidence regarding many questions.

You’re familiar with William James on “the will to believe” and the need to balance the risk of believing falsehoods against the risk of failing to believe important truths. Scientific norms tend to express a conservative attitude to inductive risk—they traditionally skew strongly towards avoiding the affirmation of falsehoods. If some important truths don’t get affirmed as a result, that’s no problem. Not my job, says the scientist, to worry about that. My job is to stick to where the evidence is most secure.

But I disagree with these conservative norms. When human attitudes towards other animals are in the balance, I think the approach to inductive risk should be somewhat different. We should think about the costs, if many other animals are indeed conscious, of a persistent refusal to acknowledge animal consciousness as real and as a legitimate target of scientific inquiry. Yes, it could be that the emerging science of animal consciousness is chasing chimeras (Dennett certainly thought this, at times)—we do run that risk—but it’s also possible, and, I would say, far more likely, that it is chasing profoundly important truths. The absolutism of a total ban on first-person evidence, even as a tentative starting point, regardless of what the cost might be in the currency of foregone knowledge, reflects a misguided approach to weighing inductive risk.

IC: It sounds like we agree on a lot, then. We agree that inferences to animal consciousness involve a deliberate loosening of some longstanding scientific strictures, especially regarding the admissibility of first-person evidence—strictures that were introduced for good reasons and that have held firm for a long time. We agree that this intentional loosening is a somewhat risky bet. You think, for Jamesian reasons, that it’s important to take that bet. I think, I guess because I fetishize “hard science”, “rigour” and whatnot—and don’t see it as my place to second-guess the wider social or political context—that these strictures should stay where they are. Shall we agree to disagree?

By Jonathan Birch

Jonathan Birch is a Professor in LSE’s Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method, specializing in the philosophy of the biological sciences. He is working on evolution of social behaviour, the evolution of norms, animal sentience, and the relation between sentience and welfare.

Further readings

Two sceptical pieces I greatly appreciate:

Dennett, Daniel C. (1995). Animal consciousness: What matters and why. Social Research, 62(3), 691–710.

Heyes, Cecilia. (2008). Beast machines? Questions of animal consciousness. In Lawrence Weiskrantz and Martin Davies (Eds.), Frontiers of Consciousness (pp. 259-274), Oxford University Press.

And two optimistic pieces from me:

Birch, Jonathan, Schnell, Alexandra K. and Clayton, Nicola S. (2020). Dimensions of animal consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(10), 789-801.

Birch, Jonathan. (2022). The search for invertebrate consciousness. Noûs, 56(1), 133-153.

I hope I’m not intruding with something obvious or obviously wrong. I have no relevant expertise.

While science has refuted some common-sense beliefs, scientists are surely not even aware of every common-sense belief they rely on during the process of science. “Animals are conscious” is a common-sense belief that hasn’t even *been* refuted, so it kinda gets my goat that “no they aren’t” is treated as a more scientific default.

Newton modeled gravity as an interaction between every bit of mass and every other bit of mass. However, (as far as I know) comets had not been observed to exert a gravitational effect on anything until after Newton had died. Was his model less scientific for having extended to every pair of masses? Would Occam tell him that a hypothetical gravitational force emanating from a comet was unnecessary to explain all known observations? Maybe gravity should not be assumed to act on bodies symmetrically, so that we can simplify gravity by saying that it acts on comets, but comets do not exert it themselves.

All of this is to say that the scope or boundaries of a model are part of the complexity of that model. Newton’s model of gravity was vastly simpler by applying to all pairs of masses, symmetrically. In a framework that admits the existence of consciousness, I don’t see it as any simpler for a model of consciousness to draw a boundary between humans and other animals, rather than a boundary that includes other animals. If science does not import the common-sense idea that animals are conscious, it should at least not privilege the notion that they are not.

The subject of consciousness is inherently complex because, by definition, consciousness is subjective. Initially, I was skeptical about the idea of animals being conscious, largely because I approached the topic in abstract terms. However, five years ago, I got a dog, which shifted my perspective. Viewing the issue through a more practical and empirical lens, I came to believe that animals are indeed conscious, albeit at a more rudimentary and limited level.