How individuals and groups are named and designated is inextricably linked to the expected outcomes of policy decisions aimed at influencing them. Discussing her recent work on these ‘objects of credence’, LSE Philosophy Professor Anna Mahtani suggests that an attentiveness to the plurality of possible designators can help policymakers be more aware of the underlying choices inherent to their work.

Policy makers often need to decide how to distribute risks and benefits across a population. Should we introduce traffic calming measures that will reduce the risk of serious injury to pedestrians, but increase journey times for drivers? Should we fund research into a new medical treatment for a severe but rare disease, or create green spaces that bring a smaller benefit to many? These are, in essence, problems of welfare distribution.

Working, primarily on the philosophy of language, I did not expect to have anything to contribute to this debate. But I came to realise that actually the two areas were connected, and an insight from the philosophy of language had implications for these problems of welfare distribution: the key point is that when you are working out the likely effects of a particular policy on a group of people, it matters how you label or ‘designate’ the people in the group.

Here’s the insight that is familiar among philosophers of language: what you believe about a person or object can depend on how that person or object is labelled. Take my colleague, Dr Brown. I see Dr. Brown around the department most days and listen to the points that he makes, and I believe that he is an excellent philosopher. In the evenings I play an online game of chess against a player called ‘Nerdslayer’, and I have no reason to suspect that Nerdslayer is a philosopher. Now suppose that, though I don’t know it, Dr. Brown is in fact Nerdslayer: then I have different beliefs about the very same person. I believe that Dr. Brown is a philosopher, but I do not believe that Nerdslayer is a philosopher.

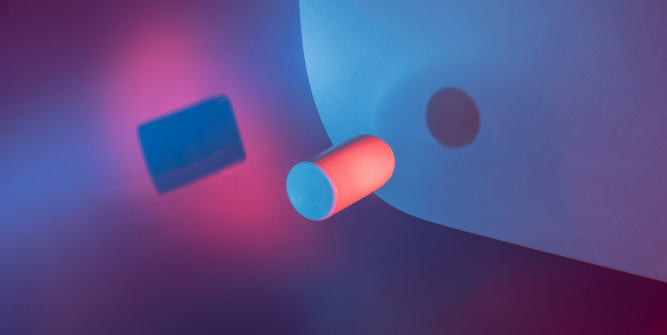

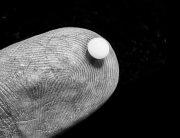

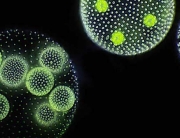

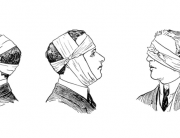

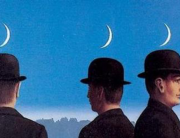

The same point can be made about degrees of belief, also known as ‘credences’, or ‘subjective probabilities’. I have a high credence that Dr. Brown (so designated) is a philosopher, and a low credence that Nerdslayer (so designated) is a philosopher, even though (unbeknownst to me) they are one and the same. In a way, then, a credence is not directly about an object or person, but rather about that object or person ‘under a designator’. My new book The Objects of Credence traces the implications of this point, and I chose the cover to illustrate the central idea: a single object can cast two very different shadows, and we might think of a credence apparently about an object as really about one of that object’s shadows.

How does this all relate to welfare distribution? It becomes relevant when we are calculating the expected costs and benefits of some policy. We often talk as though we can consider each person in a population, calculating the expected costs and benefits for that individual. But because we don’t really have credences about individuals, but rather about individuals-under-designators, it follows that when we calculate the expected costs and benefits for an individual it matters how we designate that person. Under one designator, the expected costs and benefits of some policy might be high, while under another designator, they might be low.

To illustrate this, let’s return to the case of Dr. Brown and Nerdslayer. Suppose that I am co-teaching with Dr. Brown and have agreed to complete my share of the marking by tomorrow morning. I am distracted from this task though by a really good game of online chess that I am playing with Nerdslayer. Should I keep playing chess, or stop and complete my marking? I expect that Dr. Brown will benefit from my completing my marking, while I expect that Nerdslayer will benefit more from my continuing to play. Here then we can see that my calculations of the expected welfare for a single person varies depending on how I designate him.

This has implications for some important principles. For example, the ex ante Pareto Principle states (roughly) that if you have a choice between two actions A and B, and if each individual has higher expected welfare under A then under B, then you should choose A. The principle sounds very compelling, but there is a problem: our calculations of the expected welfare of each individual under an action will depend on how we designate those individuals. Action A might emerge as giving better expected welfare for everyone under one way of designating each person, but not under another choice of designators. Thus the ex ante Pareto principle is incomplete as it stands. This is important because arguments for various positions about how welfare should be distributed rely on this principle.

My recommendation involves changing principles like the ex ante Pareto principle to explicitly refer to all the possible designators. But in practical policy choice settings a more realistic goal is to encourage policymakers to reflect on their choice of designators. If you are considering some particular set of people in making your decision, how are you designating them? Are there any other ways of designating them, and would that affect your decision? By reflecting on these questions we can get a richer understanding of how risks and benefits are distributed across the population.

By Anna Mahtani

Anna Mahtani is a Professor in the Department Department of Philosophy Logic and Scientific Method at LSE.

Credits

This article has originally been published on the Impact of Social Science Blog of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Connect with us

Facebook

Twitter

Youtube

Flickr