How do social norms influence the effectiveness of public policy, and what are the moral, political and philosophical implications of taking social norms seriously? Elsa Kugelberg looks at the effect of gender norms on health policy.

In what kind of social environment can we make choices that are valuable to us, and that we can take responsibility for? And what, exactly, can we as citizens demand from public policy?

Tim Scanlon and LSE’s Alex Voorhoeve have provided important contractualist answers to these questions. Scanlon argues that policymakers must provide opportunities that people can make use of, in order to protect themselves from danger. On his Value of Choice view, they must take the necessary precautions to make sure that if some individuals, despite having been given these good opportunities, put themselves in danger, they are still less likely to end up badly harmed. This constitutes “doing enough”. In a reply to Scanlon, Voorhoeve argues that something that should bear on the evaluation of the choices given by a policy is how we, given our internal dispositions, respond to that particular policy – how the way we actually are affects what we choose.

Social norms and HIV prevention

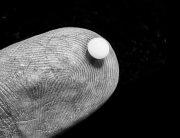

In recent empirical research on HIV prevention, it has been emphasised that something that profoundly affects what people can make out of the options provided by prevention policy is the phenomenon of social norms – informal rules for behaviour that impact people’s choices, and that are closely intertwined with expectations. An individual will likely follow a social norm if she expects that other people follow it, and if she believes that other people think she should follow it. While social norms may narrow down the bundle of opportunities open to an individual, they are also part of what makes her actions possible.

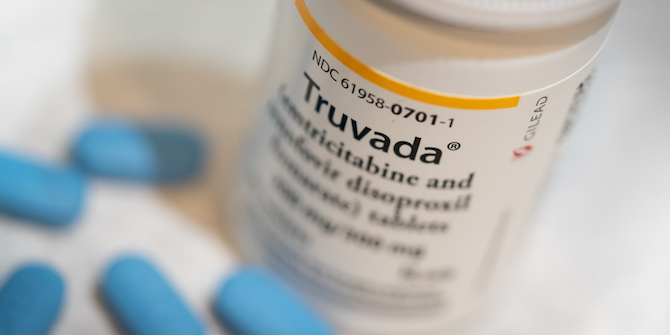

Gender norms demand different behaviours from men and women or demand stricter adherence to a behaviour from members of one gender than from other people. In societies where the risk of HIV infection is high, such norms pose a great challenge. Specifically, studies have found a set of gender norms that encourages women not to make sexual decisions or prepare in any way for sex and its consequences. These norms interfere with their choices about condom use and whether to take oral pre-exposure prophylaxis – PrEP – a drug that has been shown to significantly lower the risk of HIV infection.

Since 2015, the WHO recommends that governments provide all individuals at risk of HIV infections with the opportunity of taking PrEP, and presents it as “especially important for women, including young women, adolescent girls and also those who are concerned about acquiring HIV in the context of a stable partnership”. It is intended for, among others, “people who lack the negotiating skills and power to insist on condom use”.

Clearly, then, gender norms that discourage the use of PrEP have worrying consequences. In fact, UNAIDS points to policymakers’ insufficient attention to gender inequality and as an important explanation for the inability to curb the global HIV pandemic. And the predicament of the women in question is clearly wrong in and of itself. But exactly how should the existence of harmful social norms affect the evaluation of policies?

The value of choice under social norms

Neither Scanlon nor Voorhoeve discuss social norms, but the contractualist Value of Choice view is nevertheless a valuable resource for thinking about precisely this question, namely what kind of precautions policymakers need to take to be able to argue that they have done enough for citizens.

The Value of Choice view holds that you can be held substantively responsible for the outcome of your actions under a policy if that outcome is a result of your own doing, and something that you could have avoided by choosing differently among sufficiently good options. If you can be held substantively responsible, your complaint against the policy weakens.

If someone can be substantively responsible, this affects the strength of her complaints against a policy, and this affects whether her complaints should be prioritised over other considerations. But substantive responsibility does not necessarily change anything vis-à-vis policymakers’ obligations to assist those who fare badly. Applied to this case, this means that the choice not to take PrEP does not imply people’s giving up the right to help or treatment (i.e. antiretroviral therapy) should they become infected with HIV.

When citizens’ representatives deliberate about the choice of this or that policy, they are to think about the generic reasons that people might have to reject it. Those reasons must be such that not only the individuals who have them can understand them. Instead, they have to be the kind of reason that people generally would be able to see that someone would have, were they put in the same position as the one giving it.

To understand what this means for the HIV case, let us imagine that a policy is implemented in a society where the gender norms in question apply. This policy, Universal, neglects to take gender norms into account (this mirrors the situation of many real-world societies). It also has the following features:

In other words, Universal provides opportunities that, were it not for harmful gender norms, would give people a genuine chance to take PrEP. If people really had this opportunity, they would have less reason to complain about the policy and thus possibly be responsible for their choice. In the fictional society into which we imagine that Universal is implemented, there are three agents, Anna, Bella and Charles:

- Anna would feel bad about transgressing the gender norms by taking PrEP. She would feel shame and guilt, but she also worries that she might be subjected to physical and psychological violence by her family and peers.

- Bella would feel bad about taking PrEP because of the gender norms, but her decision to do so would not affect her social status or her relationships.

- Charles’s decision to use PrEP is not affected by the gender norms, so his situation is the one predicted by policymakers.

As this case illustrates, even in situations where people like Anna and Bella are making conscious, informed choices, such choices are often part of wider social practices. Of course, PrEP rollout should be thought of as only one example among many where the success of policymaking depends on social norms. Therefore, social norms pose an important philosophical challenge to theories that focus on choice in their assignment of responsibility to individuals – such as Scanlon’s Value of Choice view.

The value of constrained choice view

In the Value of Choice framework, could Anna and Bella reject the policy Universal, based on the fact that they are constrained by social norms from taking PrEP, that is, from choosing something they would otherwise have preferred? Or, could they be held substantively responsible for their choices? This, I believe, turns on two things. First, can we stretch the contractualist framework so that it sees reasons based on such norms as generic reasons? Second, is it plausible to argue that policymakers have far-reaching duties to take social norms into account in their work, and that they must take precautions to counter their effects, in order to be able to say that they have ‘done enough’ for their citizens? My answer to these questions is yes, with some modifications and clarifications.

On my suggestion for such a development or extension of Scanlon’s theory, which I call the “Value of Constrained Choice view”, we look at an agent’s opportunities under a particular policy in relation to the social norms that apply to agents in positions like hers. If she has opportunities that, taking such norms into account, are valuable, she can be held substantively responsible. Let’s see how we get there.

To understand the relationship between people’s generic reasons and policymakers’ having done enough, it is useful to turn to Scanlon’s own thought experiment, featuring a community whose water supply is threatened by hazardous waste. Public officials agree that to fix the problem, the waste is to be transported away from the community and safely taken care of elsewhere. Unfortunately, they predict that while the material is being removed, some of it will pollute the air to make it dangerous to breathe. Therefore, the policymakers must make some paternalistic efforts. In sum, they implement the following policy:

Inform Everyone: Fences are put up around the excavation site. To make the material as safe as possible, it is wet down before its transportation. Information about the danger is sent out to everyone in the community to advise them against going outside.

This is all that could reasonably be expected in terms of warning and protecting the inhabitants. Thus, enough is done, and no one has a generic reason to reject the policy – not even “Curious”, an individual who chooses to go outside. She is so curious to see what is going on that she ignores the warnings and her lungs are harmed. Scanlon argues that by making this informed choice, she cannot complain about this. Curious is substantively responsible for the situation she ends up in since Inform Everyone placed her in sufficiently good conditions.

The question we are examining is how a contractualist account can explain the moral and political implications of social norms’ impact on our choices. We are now in a position to compare what Scanlon says about Curious with the situation of Anna and Bella, who are choosing whether or not to take PrEP in the presence of harmful gender norms.

It is important to note why Curious does not get to term her reason to reject the policy Inform Everyone a generic reason. Even though health is something that most people value, and that generally people could see that she will put in harm’s way by not listening to the warnings, most people would see that the options she has are actually good enough for her to be able to protect herself. If she stays in her home, she will be very curious, but other than that she is fine. She has a good option: to listen to the warnings and cozy up inside while the hazardous waste is being removed. The fact that she is too curious to take advantage of it is extremely regrettable, but it is not something to alters our moral evaluation of her situation.

By contrast, Anna is in what feminists call a double bind: she has only two bad options. Either she takes advantage of the option given by the policy Universal – to take PrEP – and then she risks punishment and social deprivation. Or she does not take this option, and instead risks HIV infection. Her situation is importantly different from Curious’s, so contractualists should not treat it the same. If put in Anna’s situation, most people would generally see the value in being given better options to choose from, which shows that she has a generic reason to reject Universal. She is not substantively responsible for her outcome. Further, we can see that in order to have “done enough”, policymakers must do more to counter the harmful gender norms.

Bella, on the other hand, is in a position that bears more resemblance to that of Curious. She has one option that is good but comes with some discomfort – she can take PrEP but only by accepting feelings of shame and guilt. This, perhaps, could at least be compared to the opportunity Curious has of staying inside but being incredibly curious about what goes on outside. Scanlon discounts Curious’s internal disposition as irrelevant – she is substantively responsible for choosing in accordance with her curiosity. So why should we not say the same thing about Bella? After all, she is willingly choosing to put herself in harm’s way even after having been exposed to policymakers’ warnings.

Policy implications: prioritising the social

In the PrEP case, it is society’s norms that encourage Bella to choose to risk harm. In Curious’s case, the community’s norms do not, as far as we know, say anything about how people should choose. The fact that Bella’s problem has social roots of the kind that Curious’s lacks, makes a difference in two ways. First, treating these cases in the same way even though they have different causes is likely to lead to inefficient policymaking. We shouldn’t use our limited public funds on policies that are likely to fail. In this case, studies consistently show that treating women in conditions of high risk of HIV infection as “imprudent” choosers, rather than subjects to harmful social structures, simply does not work. The consequences are both humanely and politically indefensible.

Arguably, the difference between an agent’s internal disposition and the social norms that apply to her is not always clear cut. Nevertheless, as far as it is possible to make out the difference, this difference also has moral and political significance. The reason that women like Anna are in these difficult circumstances is that they are socially oppressed by others – it is because of the wider society that her situation is harmful. Policymakers, as representatives of the community as a whole, thus bears some responsibility for the bad effects of the norms. Together with the formal rules or policies that our institutions implement, social norms are the terms which govern our common life in society – terms which, according to contractualism, should accord with what we owe to each other. This gives us – and anyone who acts as our representative – a further reason to counter their effects and provide special precautions so that women are given truly valuable opportunities.

But what exactly should policymakers do to ensure that women – and everyone else in the community – has valuable opportunities? What precautions policymakers must take will depend on the specifics of each case. But generally, to make the Value of Choice view a viable tool for policymaking, we need to supplement it with additional principles. Specifically, it needs to be able to take social norms into account. On what I earlier called the “Value of Constrained Choice view”, we look at an agent’s opportunities under a particular policy in relation to the social norms that apply to agents in positions like hers. If she has opportunities that, taking such norms into account, are valuable, she can be held substantively responsible.

Social norms often affect and even determine how we act and what we choose. Building on this insight, my view judges that public officials are obliged to do research to find out about the social norms that exist in their society. This demand is not limited to the PrEP policy I have been discussing, or to the issue of gender. Rather, on the Value of Constrained Choice, policymakers must take a perspective that incorporates all forms of social disadvantage. To argue that they have ‘done enough’, they must conduct further theoretical and empirical research and uncover how patterns of inequalities of opportunities play out in their society.

The Value of Constrained Choice view would, when applied to the PrEP case, demand that policymakers do the research needed to reveal that Universal in fact can be reasonably rejected by both Anna and Bella. Based on studies of people’s reactions to PrEP, we can expect that Universal will not be enough to provide valuable opportunities for many women. So, what should we do instead? Based on research on PrEP policy, I propose the following policy:

Target includes the efforts taken on Universal. Further, thorough empirical research is undertaken to find out how social norms affect the choices facing different groups. Based on these studies, precautions in the following form are taken: PrEP is advertised by health officials in non-traditional venues such as nightclubs and beauty salons to reach young women. To counter the internal and external sanctions of the gender norms, in-person and online counselling is provided. Care is taken to make the clinics and packaging discreet so that individuals can take PrEP without their social network finding out, to eliminate the need for women to bargain with their partners over use of protection. Support is given to women’s organisations. Community centred programmes aimed at changing gender norms are rolled out.

This policy does a much better job at providing everyone in the society at hand with truly valuable opportunities. It puts Anna, Bella and Charles in a position of the kind only Charles was in under Universal: they can take advantage of the good option and avoid the harmful one. It is the option that policymakers, because they did not pay attention to gender norms, thought people would have on Universal.

Target is based on empirical research on the affected population. It is plausible from a feminist perspective, because it combines a gender-transformative approach, by seeking to change oppressive norms, and a gender-sensitive one, aimed at providing those who presently live under such norms with opportunities that are valuable given said norms, and which protects them from risks in the meantime. By implementing Target, in other words, they have “done enough”. What about generic reasons? Might any member in the community have one of those to reject the policy?

As I have portrayed this case, no. It appears that Charles’s situation is not impaired – he is as well off as he was under Universal, so it is unlikely that he has a complaint and likely that he can be held responsible for his choice. However, whether or not Target is found to be the best course of action will depend on what other policies it competes with for resources. Perhaps someone would be harmed if one of Target’s competitor was scrapped. I am bringing this complication up to illustrate the difficulties that are involved in all policymaking and politics.

What we can say is that we have established that Bella has a weighty complaint against Universal, based on a generic reason. From Anna’s standpoint, there are even stronger reasons to reject Universal. In the presence of the harmful gender norms it does not even provide her with a genuine choice. Instead, all options constitute extreme health risks. When we put ourselves in Anna’s standpoint, we see that Universal is, in fact, a partial policy that should be rejected in favour of Target. The Value of Constrained Choice tracks these considerations by explaining when and to what extent choice matters in the presence of biased social norms. This counts in favour of Target.

The Value of Constrained Choice view can explain why taking into account the informal rules already present in our societies is crucial when we decide how to hold each other responsible for choices. Contractualism is about finding terms on which we can live together. Therefore, this clarification is very much in line with the spirit of the wider framework.

By Elsa Kugelberg

Elsa Kugelberg is a DPhil candidate in political theory at the University of Oxford and a contributing writer and columnist for the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter. Her current project is about contractualism, sex and social norms. Elsa is an LSE Philosophy and Public Policy alumna and first started exploring questions relating to gender, HIV and contract theory during her time at LSE.

Website: https://www.politics.ox.ac.uk/person/elsa-kugelberg

Twitter: @elsakugelberg

Further reading

- Kugelberg, Elsa (2021) Responsibility for reality: Social norms and the value of constrained choice. Politics, Philosophy & Economics. 2021;20(4):357-384. doi:10.1177/1470594X211052653

- Voorhoeve, Alex (2008) Scanlon on Substantive responsibility. Journal of Political Philosophy.

- Scanlon, T. M. (2013) Reply to Zofia Stemplowska. Journal of Moral Philosophy.

- Scanlon, T. M. (1998) ‘Responsibility’ in Scanlon, TM (1998) What We Owe to Each Other. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Featured image: Tony Webster from Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons