In the first of this two-part series, Joe Mazor looks at media impartiality, what it is, and when and why it’s important.

Most people say they want impartiality from their news sources. Yet many people also believe that the media is failing to cover political issues impartially.1 But what is media impartiality? When is impartiality important? And why is it important for a society to have impartial news sources? These are the questions I will consider in this blog post.

I will argue that non-partisan news organisations’ political coverage should be sufficiently even-handed to ensure that the audience cannot discern the political views of the journalists who contributed to the coverage. The commitment to this type of strict impartiality safeguards the wisdom of the voting public, fosters democratic legitimacy, and mitigates social polarisation.

In a companion blog post (Part 2), I will consider the question of how the media can achieve this kind of strictly impartial coverage.

What is Impartiality? Basic vs. Strict

Certain requirements of impartiality are basic. News coverage should be free from racism, sexism, and bias against particular religious, national, or ethnic groups. It should not include explicit editorialising, nor should it be shaped by beholdenness to certain parties covered in the story. These basic requirements of impartiality are uncontroversial.

Yet these basic requirements do not seem to fully capture the demands of impartiality. After all, while news coverage in the Guardian and the Telegraph meets these requirements, few would call these newspapers “impartial”. It seems, then, that impartiality in the full sense of the term must go beyond these basics.

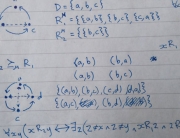

A more demanding standard of impartiality is set out in the ethical guidelines of the Los Angeles Times: “A fair-minded [and I would add well-informed] reader … should not be able to discern the private opinions of those who contributed to [a news story’s] coverage, or to infer that the newspaper is promoting any agenda.” I call this standard strict impartiality.

There is little doubt that the Guardian and the Telegraph are not impartial in this stricter sense. There is a kind of skew to these newspapers’ choice of stories and to the way in which they cover stories that makes it easy for a fair-minded, well-informed reader to discern the views of these newspapers’ journalists. Thus, strict impartiality seems to better capture the type of even-handedness that many people want from their news sources.

When Is Strict Impartiality Important?

However, I do not wish to argue that every news organisation and every news story must be strictly impartial. Partisan news sources like the Guardian and the Telegraph play a valuable social role. Their coverage can highlight important political problems and challenge public officials on the opposing political side in ways that might be overlooked by less passionately partisan news organizations. Also, the audience’s knowledge that these newspapers cover stories from a particular ideological perspective mitigates some of the problems with partiality that I will discuss below. Moreover, since most people are non-partisan and value impartiality, news sources with explicit partisan orientations like the Guardian and Telegraph are unlikely to be the dominant news sources in society, at least as long as attractive, less explicitly ideological news sources exist. Thus, I only wish to defend strict impartiality as an ethical requirement for non-partisan news sources – news sources that claim to be impartial (or that are broadly seen as impartial and do not explicitly disavow a commitment to impartiality).

Yet even in the case of non-partisan news sources, I do not claim that all stories must be covered with strict impartiality. There is little problem if, say, the audience can tell that a journalist believes that a concert she is covering was very good. My claim instead is that non-partisan news sources should adhere to strict impartiality in their coverage of political issues. I now turn to the question of why strictly impartial political coverage is important.

Preserving the Wisdom of the Crowds

The first key benefit of strictly impartial political coverage is the preservation of “the wisdom of the crowds”. In the democratic context, this is the capacity of the public to reach wise decisions on matters of public policy.

To explore this benefit, it is useful to examine a concrete case of biased coverage. Consider the following piece from the BBC about the steps Toronto has taken to reduce the bird deaths in the city. Though not a traditional news story, this piece does relates to a policy controversy. And it clearly fails to meet the requirement of strict impartiality. The only people interviewed are in favour of the policy, and no arguments against bird-proofing buildings (e.g., the loss of aesthetic value and the economic costs) are mentioned. This skewed coverage makes it obvious to a fair-minded audience member that the journalists who produced this piece are in favour of Toronto’s bird-protection policy. Yet, needless to say, many Torontonians (e.g., those who like the aesthetics of all-glass buildings and developers who have to bear the costs of the bird-friendly regulations) may disapprove of this policy.

But why is this failure of strict impartiality a problem? After all, while the BBC piece is not strictly impartial, the audience is free to seek out other perspectives. In doing so, the audience can gain a balanced understanding of this policy issue overall.

Unfortunately, it is unrealistic to expect the vast majority of citizens to engage with a variety of news sources from different perspectives on a variety of policy issues. The average person simply does not spend a sufficient amount of their time on news, especially political news. And it is unclear how this problem can be addressed in the near future without unacceptably heavy-handed measures. Therefore, if coverage of a particular policy issue by the BBC fails to be strictly impartial, the public’s view is likely to move in the direction of the perspective favoured by the journalist, especially on policy topics (e.g., protecting birds from glass buildings) about which most individuals do not have strong pre-existing views.

Yet one could still question the problem with this outcome. After all, the average British citizen knows little about, say, the complexities of bird migration routes, the dangers of glass windows to birds, and the costs of protecting birds. The journalist, on the other hand, is intelligent, educated, and has presumably carefully considered the policy controversy she is covering. If British public opinion comes to more closely reflect journalists’ informed opinions, some might claim that this would be an improvement over the status quo.

There are, however, good reasons to be sceptical of this claim. Well-informed and thoughtful though she might be, the BBC journalist is unlikely to be as good at discerning the right policy as a large, minimally-informed, unbiased majority. The basic reasons for this surprising proposition were explored by Nicolas de Condorcet in his well-known jury theorem. Condorcet proved that, under certain conditions, the majority of a very large group of marginally competent individuals is more likely to be right than even a wise expert. This is true as long as each individual in the group is more likely than not to reach the right answer and as long as each individual’s judgment is independent. And while there are important questions about the relevance of Condorcet’s insights, there is a strong case for thinking that these insights do apply to contemporary democracies, at least to some extent and under certain conditions.

By providing coverage that favours one side of a policy debate, the journalist undermines both the competence and the independence of each audience member to judge the policy issue for herself. Thus, while the journalist might be convinced that bird-proofing buildings is a good idea, and while she may well be right on policy issues more often than the average audience member, society can nevertheless achieve better policy outcomes overall if strictly impartial coverage preserves the collective wisdom of the demos.

Democratic Legitimacy

However, even assuming that political outcomes would be just as good if public opinion simply mirrored the political opinions of, say, BBC journalists, there are two reasons grounded in democratic legitimacy for nevertheless preferring strictly impartial coverage. The first is the value of collective self-determination. One factor that makes democracy an intrinsically valuable form of government is that, at least in some sense, it allows us to govern ourselves. Yet if public opinion about policy is heavily shaped in by journalists who fail to provide the public with the arguments on different sides of policy debates, then our ability to be self-governing is compromised.

Strict impartiality also fosters democratic legitimacy because it gives individuals on different sides of political debate a chance to have their claims heard by the ultimate decision-maker – the public. So, for example, new regulations requiring building owners in London to drastically alter building designs to protect birds are more legitimate if the building owners have had a fair chance to make their case against the regulations in the court of public opinion. Coverage that is not strictly impartial undermines this type of fair hearing.

Avoiding Social Polarisation

A final key benefit of strictly impartial news coverage is the reduction in social polarisation. Consider now a society in which 45% of citizens engage with only left-wing news sources, 45% engage with only right-wing news sources, and 10% engage with both right-wing and left-wing news sources (where all news sources claim to be fair and balanced). The electoral decisions in this society might not be substantially worse than in other societies. Yet, even setting aside problems of democratic legitimacy, the media environment in this society is deeply problematic.

The 90% who listen only to one-sided political perspectives can be easily led to the conclusion that there is no minimally reasonable case for voting for the other political side. This belief can lead to the attitude that many citizens on the other side of the political divide are either stupid or malicious. The result is likely to be suspicion, dislike, and even discrimination against fellow citizens on the basis of their political views. And, as citizens associate less with fellow citizens from the other side of the political divide, they are less often exposed to competing arguments, increasing the severity of this problem.

Moreover, some partisans who do not see a minimally-reasonable case for voting for the other side might conclude that powerful, sinister forces are in control of society. After all, this would explain how the opposing political party has managed to achieve an electoral majority (or come close to it), despite its platform’s (perceived) complete lack of merit. Citizens who adopt this belief in sinister forces are likely to be less committed to democracy, since they perceive it as easily corruptible. They are also likely to demonise groups that they believe are part of the sinister forces controlling society. Finally, they are likely to be deeply hostile to the idea of compromise or cooperation with the opposing political side. The result is a far nastier form of democratic politics in which the opposing political side is seen, not as an interlocutor in a passionate debate about the common good, but rather as a malevolent enemy that must be defeated.

Needless to say, strict impartiality in non-partisan news sources’ political coverage is insufficient to guarantee the wisdom of the demos, democratic legitimacy, and a less polarised society. But it can contribute in important ways to these goals. If so, this invites the question of how news coverage can be strictly impartial. I will take up this question in Part 2.

By Joe Mazor

→ Media Impartiality Part 2

Joe Mazor is a political philosopher who is currently a visiting academic at the LSE’s Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science. His research interests include distributive justice, democratic theory, philosophy of economics, and applied ethics.

Further reading

- For a more detailed argument in favor of strict impartiality, see Section 2 of Mazor, Joseph. “International Rights Violations and Media Coverage: The Case for Adversarial Impartiality.” International Journal of Applied Philosophy 27, no. 2 (2013): 225-249.

- For more on the wisdom of the demos, see Goodin, Robert E., and Kai Spiekermann. An Epistemic Theory of Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.)

- For more on the importance of citizens’ knowledge of arguments on different sides of political issues, see Chapter 3 of Mutz, Diana. Hearing the Other Side (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.)

Notes

1 – Note that the source cited asks people about their desire for “unbiased” coverage and their belief about the “fairness” of coverage of political issues. Yet it seems plausible that people would give similar answers to questions about “impartiality”.