Should we be blamed for the negative consequences of otherwise wholly good acts? Tom Rowe considers the moral risks faced by aid givers.

Sometimes, in order to aid individuals, one must do things that will foreseeably enable evildoers to better pursue their harmful aims. Recent examples of this predicament abound. For example, the recent UN aid programme for Syria, which would allow the Syrian regime – widely considered to be engaged in abuses of its citizens – to decide how the funds were distributed. There are claims that the regime is manipulating the relief efforts for political gain.1 Another example can be taken from the 2011-2012 East African drought, in which some of the most difficult-to-access areas were controlled by the Al-Shabaab militant group, widely considered a terrorist organisation. Often, aid agencies were permitted to access these areas only if they paid off the militants. Al-Shabaab desired to co-opt and materially and politically benefit from the provision of aid.2

The following question is the subject of this blog post: are aid workers liable to blame for the harms caused by such evildoers? I shall first outline Jennifer Rubenstein’s recent attempt to answer this question, her “spattered hands” account, before providing my own answer through what I call the Moral Purity Account. To bracket the complexities of the opening cases, I shall adopt the following stylised version:

Spattered Hands

Jennifer Rubenstein (2015) has provided a conceptualisation of the predicament facing rescuers in Aid Case. According to Rubenstein, rescuers bear some moral responsibility for the foreseeable harms that evildoers commit. On the “spattered hands” account, rescuers’ hands are “spattered” by the blood of others but the rescuers’ “good intentions do not shield them from moral responsibility for the predictable effects of their actions, even if those effects are indirect” (2015; 105). This is so even if the net-consequences of their actions are positive. To be morally responsible for an action is to be worthy of praise or blame for having performed it.

According to the “spattered hands” view, rescuers cannot discontinue the provision of aid in order to “keep their hands clean”, when the benefits of their aid outweigh the costs. The account is named “spattered hands” because the hands of the rescuers are only bloodied indirectly, primarily through the actions of others. So, in Aid Case the rescuers bear some of the moral responsibility for the harms that occur indirectly as a result of their provision of aid, even though the harms were solely and directly caused by the aggressor.

Moral Purity

I argue that, contra Rubenstein, rescuers do not bear moral responsibility for the harms caused by another in situations like Aid Case. To demonstrate why this is the case, I shall consider two stylised examples. The first is the following:

I claim that it would be permissible for the rescuer to provide the medicines. Many more lives will be saved than if the rescuer did not intervene. Further, the rescuer does not intend the deaths of the 20, but rather foresees that they will happen as a result of his actions. It would be impermissible for the rescuer to intentionally kill the 20 as a means of saving the 100. It may be appropriate, however, for the rescuers to apologise and express regret with respect to the deaths, but this is not to say that the rescuers are liable to blame. A person is blameworthy for an action when her action indicates something about her attitudes towards others that impairs her relations with them.3 Now consider the following case:

This case shares the same structure as Aid Case. The rescuer should save the 100 for the same reasons that apply in Infected Rescuer: many more people will be saved, and the deaths of the 20 are not intended by the rescuer. Are the rescuers (partly) blameworthy for the deaths of the 20 if they decide to save the 100? I submit that they are not. The rescuers are not appropriately related to the deaths of the 20 to be blameworthy for them.

In Bridge Rescue there is separateness between the plans and goals of the rescuers and of the villainous aggressor. The rescuers aim only to do good, and foresee that another will cause harm as a consequence. But crucially, the harms are caused by the actions of another. This is important, because, as I have claimed, we can only be morally responsible for those acts with which we can identify. For example, we don’t identify with the actions we take under command from a gun-wielding maniac as our actions, since they were coerced.4 Whereas, we typically do identify those actions that flow from our desires and plans as our own. So even though the villainous aggressor can only carry out his harmful acts if the rescuers provide aid, the blame is fixed squarely on the aggressor because he acted from his own evil plan.

A summary of my argument is as follows. The rescuer is not blameworthy for the deaths of the twenty in Infected Rescuer. The rescuer is no more blameworthy in Bridge Rescue than he is in Infected Rescuer. Therefore, the rescuer is not blameworthy for the harm caused in Bridge Rescue. Because Bridge Rescue and Aid Case share the same structure, the rescuers in Aid Case are not blameworthy for the deaths of the 20. If this is correct, then there are reasons for thinking that, contra Rubenstein, rescuers do not share moral responsibility for the harmful acts of others when they provide aid.

By Tom Rowe

Tom Rowe is a PhD student in the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method. His thesis concerns the ethics of risk and uncertainty. In particular, he is interested in fair distribution under conditions of risk and uncertainty, as well as the ethics of risk impositions of harm.

Further reading

- Jennifer Rubenstein, Between Samaritans and States: The Political Ethics of Humanitarian INGOs, Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2015.

- T. M. Scanlon, Moral Dimensions: Permissibility, Meaning, Blame, Harvard University Press: Cambridge Mass., 2008.

- C. Seidel er., Consequentialism: New Directions, New Problems?, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2016.

- Bernard Williams, “A Critique of Utilitarianism” in J. J. C. Smart & Bernard Williams, Utilitarianism For and Against, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1973.

[1] This has recently led to 73 aid organisations suspending cooperation with the UN in Syria, due to the “significant and substantial influence” of the Syrian regime on the UN aid agencies in Syria. The letter sent to the UN from the 73 organisations can be found here.

[2] Abdi Aynte & Ashley Jackson, “Al-Shabaab engagement with Aid Agencies”, Overseas Development Institute, Policy Brief 53, 2013. See also: Ashley Jackson, “A deadly dilemma: how Al-Shabaab came to dictate the terms of humanitarian aid in Somalia“, Overseas Development Institute, 2013,.

[3] This is an account of blameworthiness that is outlined and defended by T. M. Scanlon in Moral Dimensions: Permissibility, Meaning, Blame, Harvard University Press: Cambridge Mass., 2008, p. 145.

[4] Elinor Mason explores this view in more detail in “Consequentialism and Moral Responsibility”, in Consequentialism: New Directions, New Problems?, Seidel, C. ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2016.

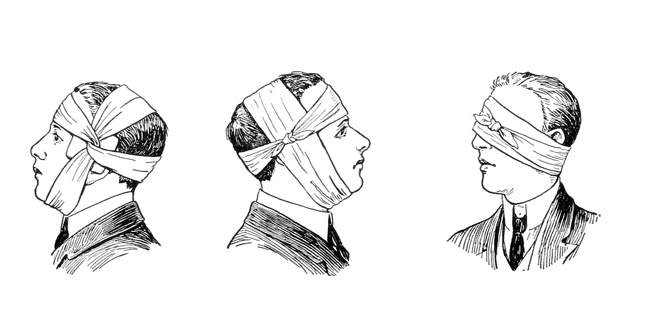

Featured Image: Public Domain

Excellent article. It would be interesting to consider some more “tricky cases”. For example, what about an aid case in which the choice of the rescuers is not between saving the lives of 100 vs. sacrificing 20 but between, say, 100 vs. 99? Does the same conclusion still hold then, or is there a threshold which, if exceeded, makes you blameworthy? If there is, it would be interesting to come up with a formal measure.

Cheers.

Many thanks for your question. I think that although the number of people saved has to be greater than the number of people who are foreseeably killed, the number saved ought to be sufficiently greater. For instance, it would not be permissible to foreseeably kill 24 individuals in order to save 25, but it would be permissible (I claim) to foreseeably kill 20 in order to save 40. It is difficult to say precisely where the boundary lies between a permissible ratio of saved individuals to foreseeably killed individuals and an impermissible ratio.

An explanation for this thought is that there are stronger moral constraints against harming people than there are against not aiding people, so more good is required in order to outweigh the harm that is caused by the evildoer. However, a consequentialist would argue that there is no intrinsic difference between harming and not-aiding, so we could provide aid in cases where 100 people are saved and 99 people are harmed, since more good is done overall. Whereas, I think that the bar for justifying harming is higher than the bar for justifying not-aiding. If the rescuers provide aid when the benefits do not sufficiently outweigh the harms caused by the evildoer, then the rescuers act impermissibly, but they are not blameworthy for the deaths that are caused by the evildoer.

Thanks,

Tom

Firstly, the article is excellent.

As I read your reply to a comment, you said that it will be appropriate to kill 20 to save 40, while it will not be appropriate to kill 25 to save 24. I wonder something like the case — the virus– which put the victims into sickness is not the outcome of what the victims have done, so this is just like a random event which may happen to you and us. That’s to say, it’s not suitable to say that kill 24 people which are not sick to save 25 people who are already sick is guilty, cause whether a person’s island will have pandemic is random then whether a person is sick is not their behaviour’s outcome. In that case, I think the amount of people is just a quantitative number, which is comparable to give a net-outcome. So I guess there may be a different kind of explanation, if the reason why the victims are in dilemma is that of their own behaviours, and especially if it’s foreseeable, they should not be saved by killing others’ lives. But this explanation is still also tricky because when the people who are in dilemma are in a large amount, it’s hard to say each individual should be responsible for that, because the decisions made by mass is often not desirable to blame everyone.

Cheers

Just found this. How are these different from the various versions of the trolley dilemma?