Ruminating on litigation’s role in bridging the policy gap on animal agriculture and its emissions

A recent case challenging the UK Government’s Food Strategy raises important questions about the sustainability of our food system and its impact on the climate crisis, an issue that is starting to find its way before other courts around the world. Emily Bradeen, Kate Higham and Joana Setzer explain.

In January, the UK’s Court of Appeal upheld the dismissal of a case brought by the non-governmental organisation ‘Global Feedback’, challenging the Government’s Food Strategy. The plaintiffs argued that in developing the Food Strategy, requirements to consider how the strategy would affect the government’s ability to meet the UK’s carbon budgets and net zero target had not been fulfilled. The case was decided on narrow statutory grounds but raises further-reaching questions.

We can understand the case as part of a growing subset of climate litigation cases concerned with how the agricultural system, and in particular animal agriculture or livestock farming, contributes to global warming. Animal agriculture generates greenhouse gas emissions at many points in its production processes, from the cultivation of animal feed to the management of animal waste. While it is challenging to pinpoint an exact contribution, animal agriculture is estimated to account for 11% to 20% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

The methane emissions produced through ruminant animals’ enteric fermentation (or digestive process) are particularly significant, accounting for over 70% of agriculture’s methane emissions. On a global level, the agriculture sector is the largest anthropogenic source of methane emissions, surpassing the fossil fuel sector. Rapid action to reduce methane emissions could help slow the rate of global warming within the next few decades; experts claim these reductions will be “critical for helping keep the world on a path to 1.5C”. In recent years, attempts to regulate methane emissions from animal agriculture have faced public backlash and resulted in policy reversals. While eating less meat and dairy could help to reduce methane emissions significantly, it remains unpalatable for consumers and governments alike.

However, the environmental and climate impacts of animal farming extend far beyond methane emissions, as the industry drives large-scale deforestation, land conversion and the use of energy-intensive and polluting fertilizers. Burning forests to clear land for animal feed production and livestock releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere; but even less devastating forms of land conversion release carbon stored in trees and soils, and simultaneously reduce the planet’s carbon sinks. In addition, the production and use of artificial fertilizers, which are heavily relied upon to grow animal feed, generate large quantities of nitrous oxide – a greenhouse gas that traps significantly more heat than carbon dioxide.

Responses to address these emissions are currently inadequate, due to either a lack of regulation or weak enforcement of the regulations that do exist. As a result, litigation has come to the fore as a governance strategy to address this gap.

An emerging area in climate litigation: towards the ‘Methane Majors’?

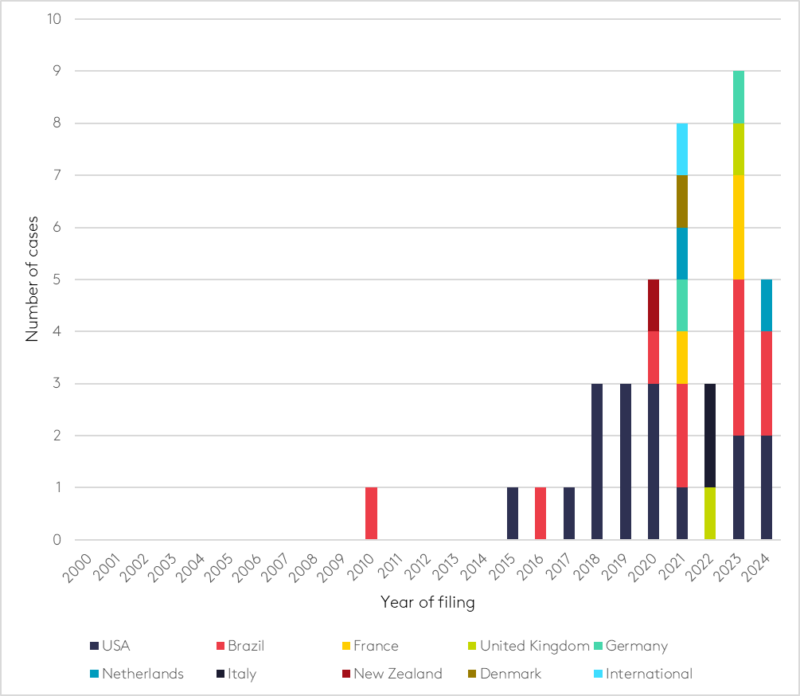

In 2024, Daina Bray and Thomas Poston published the first comparative survey of climate change and animal agriculture litigation, which our dataset builds on. Animal agriculture litigation forms a small subset of cases in the larger climate case corpus at around 40 cases out of roughly 3,000 (the first case was filed in 2010 – see Figure 1). While most of the cases identified seek to establish accountability for animal agriculture’s contribution to climate change, they include a broad range of arguments and types of defendants. As in other areas of climate litigation, we are beginning to see more cases draw on the intersection of climate change and human rights, challenging some of the practices used for animal agriculture on both climate and human rights-related grounds.

Figure 1. Animal agriculture cases filed over time

Within the animal agriculture subset, two jurisdictions stand out for the volume of cases filed: the United States, which accounts for almost half (16) of these cases, and Brazil (10 cases). This is perhaps unsurprising given these countries are two of the world’s largest producers of livestock. In the US, most cases challenge the exemptions granted to ‘Animal Feed Operations’ and livestock producers from complying with environmental regulations. Other cases contest the failure to adequately consider the emissions impact of animal agriculture projects in licensing processes, or dispute claims made by meat producers about their climate impacts and transition planning.

Brazilian cases are largely concerned with the enforcement of environmental regulations and seek compensation for the unlawful deforestation of the Amazon by large-scale cattle farmers and agribusinesses. The defendants’ activities, which include cattle ranching and land clearing for animal crops, are claimed to have resulted in climate damage through the loss of carbon sinks and the emissions released from burning forests. While this does not account for the full lifecycle of emissions created by the defendants, these cases nonetheless represent a novel approach to applying the ‘polluter pays’ principle to the climate context. Brazil is also the only jurisdiction where criminal proceedings have taken place, resulting in the imprisonment of cattle ranchers.

Since 2020 there has been a diversification in the jurisdictions where these cases are being brought, with an increasing number outside the US and Brazil. A particularly significant case is Smith v. Fonterra Co-Operative Group Limited, which seeks to establish that the defendants, including New Zealand’s largest dairy cooperative, owe Mr Smith, the plaintiff, a ‘novel’ duty of care to cease contributing to damage to the climate system through their emissions. The Supreme Court allowed the case to proceed to trial, and the forthcoming decision is expected to play a critical role in shaping how common law tort claims might respond to climate change.

In parallel, we are also seeing a diversification of defendants. While earlier animal agriculture cases typically targeted governments and large-scale cattle ranchers, newer cases have started to challenge a group of companies referred to as the ‘Methane Majors’. According to a 2022 report, these companies, comprising the five largest meat and 10 largest dairy corporations, are collectively responsible for methane emissions which equate to over 80% of the EU’s entire methane footprint, or around 3.4% of all global anthropogenic methane emissions. We may now be witnessing the early stages of increased litigation against the Methane Majors, just as litigation against the Carbon Majors intensified following Richard Heede’s report.

However, the cases are not limited to the companies that are directly responsible for the emissions. Complaints have also been lodged in a variety of forums against supermarket chains and the textile industry over the impacts their supply chains have had on exacerbating livestock-related deforestation, in addition to violating the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Companies are also being sued over upstream emissions related to animal agriculture, and banks are under scrutiny for their ‘financing’ of animal agriculture-related emissions. In line with developments involving other sectors, litigants are bringing ‘climate-washing’ cases that challenge agricultural companies’ carbon neutrality and sustainability statements.

This range of cases suggests that animal agriculture is likely to remain in the sights of litigators. Advances in satellite imagery may also provide further evidence for future litigation. Brazilian Federal Police currently use satellite imagery to enforce environmental laws and prevent deforestation in the Amazon. With improvements in how emissions can be measured through imagery, methane detection could equally be used by agencies seeking to address emissions from the agriculture sector; specialist companies are already beginning to gather data on potential emission ‘hot spots’. This imagery could also help to identify animal agriculture super-emitters that fall outside of the Methane Majors, and could bolster source attribution claims made in cases.

Policies and litigation must account for social impacts

At the same time, the implications that climate change holds for farming cannot be overlooked. Climate-driven increases in water scarcity, extreme weather events, and changes in the number and distribution of pests hold negative consequences for crops, livestock and farmers’ livelihoods. In response, some farmers are beginning to take legal action against companies and governments over the harmful impacts they are currently experiencing, and the anticipated worsening of conditions due to inadequate climate action.

This type of litigation is likely to become more frequent, as affected communities and civil society groups turn to the courts to fill governance shortcomings in countries’ climate responses. To mitigate the risk of litigation, governments should be more proactive in ensuring that farmers are supported in the transition to low-carbon economies. In addition to regulating emissions, attention must be paid to incentivising innovation – such as technologies that can capture or reduce emissions from the agriculture sector – and assisting farmers with the costs associated with adapting to climate impacts.

Litigators must also develop awareness of the potential distributional impacts associated with a transition in the agricultural sector. In developing litigation strategies, litigators should engage constructively with communities that are economically dependent on livestock and farming, supporting policy frameworks that advance a just transition. Failure to account for these social dimensions risks fuelling the kind of political and societal backlash that has already delayed action on agricultural emissions in major exporting countries.