What role do catastrophe bonds play in managing the physical risks from climate change?

The challenge of physical climate risks

Extreme weather events such as severe droughts, heatwaves, tropical cyclones, heavy rainfall and floods are increasing in frequency and intensity due to climate change. This is amplifying the substantial physical risks they pose to humanity, nature and the built environment. Rising vulnerability to climate-related impacts is in turn raising the cost of debt for developing countries. Emergency responses to natural hazard-related disasters can also lead to a reallocation of government budgets for the provision of aid, possibly away from other priority investment areas.

In light of these challenges, policymakers are increasingly considering how to ensure financial stability and climate resilience in their fiscal and economic policies and risk management practices. More traditional options employed under the umbrella term ‘disaster risk finance’ include extending insurance protection and setting up reserve funds, but an additional, more specialised, financial instrument is gaining increasing attention in this context: catastrophe bonds.

What are catastrophe bonds and how did they emerge?

A catastrophe bond is a financial instrument that transfers financial risk connected with exposure to natural disasters to capital market investors. Catastrophe bonds have their origins in the aftermath of several major natural disasters that struck the United States in the 1990s and caused the insurance and reinsurance industry to reevaluate their methods.

Insurance companies typically turn to the reinsurance sector (which provides insurance for insurance companies) to transfer some of the risks on their own balance sheets to another company. However, with the increasing frequency and intensity of catastrophic events, reinsurance protection has become uneconomical, particularly for larger events that threaten to incur high costs for the insurance sector. This has created the need for alternative sources of protection. When Hurricane Andrew struck the southern US in 1992, it caused over US$26 billion (approximately US$80–100 billion today) in physical damage, triggering the bankruptcy of 11 insurance companies and causing a significant re-evaluation of risk exposure across coastal areas of the US. In response, insurance companies reduced their exposure to hurricane risk and increased insurance premia for communities in affected areas, at a time when households and businesses were seeking more insurance coverage against potential future hazards.

Hurricane Andrew provided a wakeup call for the insurance sector to enhance capacities to quantify, price and manage risk, and marked the start of the industry’s rapid adoption of catastrophe risk modelling. Public catastrophe funds were set up to address the market failure resulting from a lack of capital. The first catastrophe bond was issued to diversify the risk from one reinsurer across multiple capital market entities to further improve capital management in the sector. A large share of the market for catastrophe bonds has since provided protection against ‘primary perils’ (e.g. hurricanes and earthquakes), particularly in the US and Japan. However, the catastrophe bond market is now also growing in other regions and is increasingly covering ‘secondary perils’ (e.g. floods, droughts and wildfires), which are becoming more frequent and intense and thus posing increasingly severe financial impacts.

Issuers of catastrophe bonds have mainly been private actors such as insurance and reinsurance companies in advanced economies. However, in developing countries, governments (e.g. those of Jamaica and the Philippines) and non-governmental organisations (e.g. the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility/CCRIF) have also issued ‘sovereign’ catastrophe bonds, often with the support of multilateral development banks.

How does a catastrophe bond work?

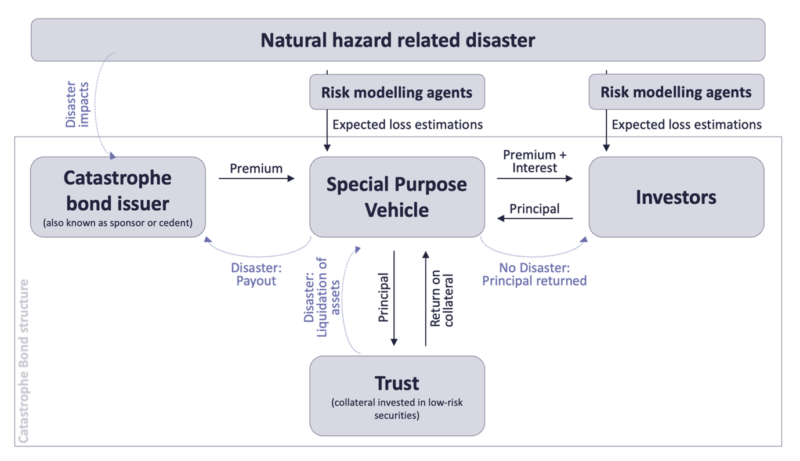

A catastrophe bond moves risk from an issuer to an investor in return for interest payments (see Figure 1). When a natural hazard-related disaster meets predetermined conditions, the issuer receives a payout from the bond, which reduces the original sum of capital (principal) invested.

Figure 1. Structure of a typical catastrophe bond

Source: Author, adapted from Braun and Kousky (2021)

How suitable and effective are catastrophe bonds?

The use of catastrophe bonds has sparked debate, especially their use by sovereign states in the context of international development. Concerns have been raised around the broader trend towards the ‘financialisation’ of natural hazard-related disasters and the implications of catastrophe bonds for a country’s sovereignty.

The significant transaction costs and resource commitment associated with catastrophe bond issuance raises questions about the cost-effectiveness of these instruments, particularly as the bond structure usually focuses on transferring risk rather than reducing it.

There has been some criticism of complex disbursement rules that resulted in delayed payouts of ‘pandemic bonds’, which have a similar financial structure to catastrophe bonds. Plans to issue more pandemic bonds were shelved by the World Bank as a result. If catastrophe bonds for natural hazard-related disasters also come to be seen as overly complex and ineffective, proceeding with their issuance may prove challenging for governments.

Catastrophe bonds with a parametric trigger structure – whereby the payment amount is set based on the magnitude of the event rather than the magnitude of the losses – often face questions about how the thresholds are determined. Hurricane Beryl which struck the Caribbean in July 2024 provides an example: despite causing extensive damage to infrastructure and plantation crops, there was no payout from the catastrophe bond because the minimum air pressure stipulated for prompting a payout was not reached in any of the areas covered by the bond. Instead it was expected that payouts of up to J$4.5 billion would come from Jamaica’s own contingency fund and natural disaster fund, which form part of a multi-layered disaster risk financing strategy.

The effectiveness and limitations of catastrophe risk models in capturing changes driven by climate change are an ongoing topic of debate. While empirical studies are limited, one study suggests that catastrophe bond transactions from 1997 to 2017 significantly underpriced natural catastrophe risk. Carrying out major updates to models has been shown to be challenging: for example, after the leading modelling agency implemented a major update to its models in 2011, risk factors for catastrophe bonds increased on average by a factor of three, which caused a breakdown in confidence in the models and prompted nearly all users to switch to the competing agency. Nevertheless, more major updates will be needed to reflect the increasing and changing risks in the context of climate change, in conjunction with factors such as population growth, inflation, new infrastructure, asset accumulation and urban expansion. Shifting paths of tropical cyclones or the promotion of electric vehicle infrastructure could give rise to new risks, for example.

Discussions about the catastrophe bond market more broadly are ongoing. Although market initiatives are underway with the objective to enhance the transparency of catastrophe bonds, particularly with regard to the underlying insurance policies, progress has been slow. Some private institutions have issued green catastrophe bonds, which ensure that collateral is invested in low risk, liquid and sustainable securities (e.g. EBRD green bonds), but such transactions remain limited.

What is the likely future for catastrophe bond issuances?

Despite the debates and concerns described above, investors are increasingly interested in the catastrophe bond market, drawn to its attractive yields and low correlation with conventional risks, particularly during periods of high market volatility. Catastrophe bond issuance reached record levels in 2023 and demand for prearranged financial instruments is expected to continue to grow.

In advanced economies, both corporate entities and financial regulators are increasingly interested in catastrophe bonds. Catastrophe bonds are also gaining traction for their sustainability profile: many catastrophe bond funds are already classified as ‘Article 8 compliant’ under the current EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (i.e. they are funds that will be used to promote environmental and social objectives).

In emerging markets and developing countries, issuances through multilateral development banks and the coverage of secondary perils such as floods and droughts are expected to grow. By mid-2025 the World Bank could issue its first drought catastrophe bond, likely focused on Africa. It also plans to significantly expand its catastrophe bond support in general, aiming to increase issuance by 400% until 2028. Pooled insurance solutions, such as the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility, have been in existence for some time and have used catastrophe bonds in the past. There is a growing interest in other regions in establishing similar structures, such as the African Risk Capacity, which already has a parametric drought insurance scheme in place.

Following the momentum gained in establishing and funding a Loss and Damage facility at the COP28 UN climate conference in 2023, there has been an increase in interest in identifying appropriate financial mechanisms, with catastrophe bonds mentioned as a potential instrument.

How could catastrophe bonds evolve?

With the increasing frequency and severity of physical climate risks, the growth in exposed communities and assets, and maturing global capital markets, there will be a greater demand from governments for financial mechanisms to deal with such risks. Financial innovation can help to improve existing structures, for example to enhance the desired positive effects for communities.

Some innovative suggestions have been made, such as the potential for environmental impact bonds, resilience bonds and climate resilient development bonds. However, none of these has yet gained significant traction, which may be indicative of the difficulties in designing financial products that both appeal to investors and offer a favourable arrangement to governments.

This Explainer was written by Lea Reitmeier, with review by Joe Feyertag, Maeve Sherry, Denyse Dookie and Paul Wilson, and editing by Natalie Pearson and Georgina Kyriacou.