Depression, anxiety, and psychosis experienced by women in the UK costs an estimated GBP 8.1 billion. As well as its deep repercussions for mothers, children, and families, perinatal depression and anxiety are costing public sector systems and country budgets. By modelling the costs for perinatal mental health problems as well as costs and benefits of scaling prevention and treatment we make the case for investing in more maternal mental health initiatives, in the UK and beyond. This Maternal Mental Health Week, we share some of the key developments in methodologies, and how we adapt those to countries across the world.

Estimating the costs of perinatal mental health problems

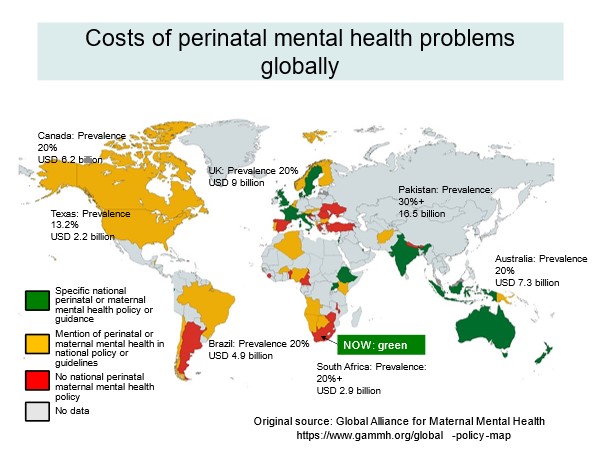

Our cost methodology that we first developed in the UK has since been replicated in many countries such as Canada, Australia, and France (see map below). We have adjusted the methodology for low- and middle income countries, and have calculated that estimated costs of untreated perinatal depression and anxiety are USD 2.8 billion in South Africa, USD 4.9 billion in Brazil and in USD 16.5 billion in Pakistan, reflecting the high prevalence and large impacts on health, quality of life and productivity.

Such cost figures are in many ways crude, and inevitably based on assumptions, but they can be powerful instruments to policy makers, if presented alongside other evidence, and information, including the voice of families with lived experience. Some governments already use this evidence when developing policies or planning budgets. For example, the work informed major policy reforms and investments in the UK, and informed the new mental health policy in South Africa.

These lifetime costs pertain not only to women but also take into account a range of other factors, including child growth, health, and development. Direct impacts taken into account in our cost modelling methodology depend on country context but can include:

Translating economic evidence into policy

Economic evidence cannot be easily generalised from one country to another hampering therefore relevance to policy makers. Costs strongly depend on health service systems, population characteristics, socio-political environments, gender inequalities, as well as other factors. In addition, policy makers might not have the time, skills, or knowledge to engage with such evidence unless it is communicated to them appropriately. In partnership with in-country stakeholders who are experts in the topic in the cultural and political context, and who advocate for change, we seek to produce economic evidence that translates into policy change.

For example, in the UK, the Maternal Mental Health Alliance is a well-established network of over 125 organisations with expertise and dedication to influence policy change. Similarly, the Global Alliance for Maternal Mental Health, a network of international organisational and sub regional alliances, such as the African Alliance for Maternal Mental Health, disseminates evidence on the human and economic costs and evidence-based solutions to policymakers to influence change. We work closely with these Alliances and organisations promoting policy change, such as the Perinatal Mental Health Project in South Africa, or PAM Foundation in Thailand, to take our economic findings, and present them in digestible formats to policymakers – this way cost modelling is more likely to contribute to tangible change for those affected by perinatal mental health problems.

Towards cost-effective solutions for perinatal mental health

High-quality evidence, informed by a large number of randomised controlled trials conducted in several parts of the world for different groups of women, show that psychosocial treatment during the perinatal period works, is good value for money, and can be scaled in ways that are economically viable. Our modelling shows that investing in integrating mental health into maternal and child healthcare, in line with international guidance by the World Health Organization, not only leads to an increase in quality-of-life but can lead to savings of up to £26.6 million over a ten years period in England. The estimated benefits are likely to be conservative because they refer to only one outcome: health-related quality of life from a mother’s perspective. This means that the positive impacts of treatment on other maternal, paternal and child outcomes are underestimated. At the same time, treating perinatal mental illness alone is most likely not enough to avert the many adverse impacts of perinatal mental health problems.

Ultimately more is needed to break the cycle of intergenerational transmission of poor mental health. Interventions that, in combination, address a range of social determinants of mental health, including poverty, racism, gender disadvantage, other forms of discrimination and violence, are more likely to be effective and (cost-)effective. Overall, there is only limited evidence about how to best address those determinants to prevent child impacts. However, some integrated programmes [a, b, c] of have shown that that can be cost-effective, because of their ability to prevent adverse consequences such as child maltreatment and improve in women’s financial situation and empowerment.

What needs to happen next?

A main evidence gap remains about how to best provide cost-effective interventions for women at scale, in different contexts. In other words, how to adapt interventions to specific contexts in ways that are affordable, feasible and acceptable. Delivery methods such as task-shifting or -sharing and the use of digital technologies hold promise in scaling interventions cost-effectively, and are currently being tested. Culturally appropriate interventions available to women during the perinatal period also have an important role in treatment, especially if they are co-designed with local stakeholders, and can be incorporated into existing community structures. This may be offered alongside singing, arts, physical or other social activities.

Economic evaluation, if delivered in participatory ways, has an important role in informing the scaling of perinatal mental health interventions. This is especially true in contexts where there is little routine data available to inform decisions, and scaling interventions is prevented by a lack of resources. We have been working in in several low-and middle-income countries, including most recently in Thailand (PAM Foundation), to systematically involve stakeholders in deciding the scope of economic analysis that is most relevant to their resource allocation problem. Moving forward, we hope to expand this work across other contexts and make sure that economic evidence can be used alongside other evidence and information, including from families with lived experience to make more informed policy decisions about maternal mental health interventions.