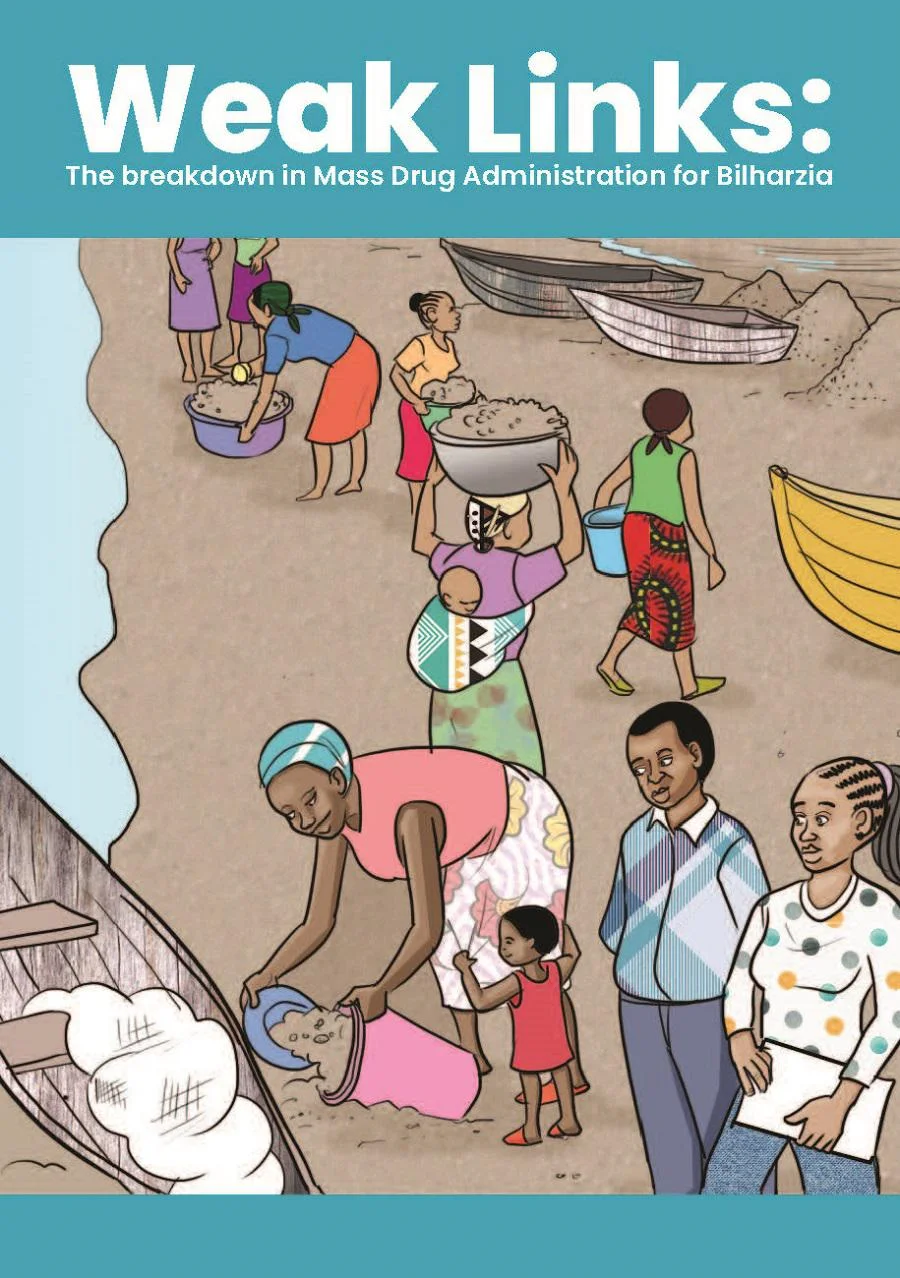

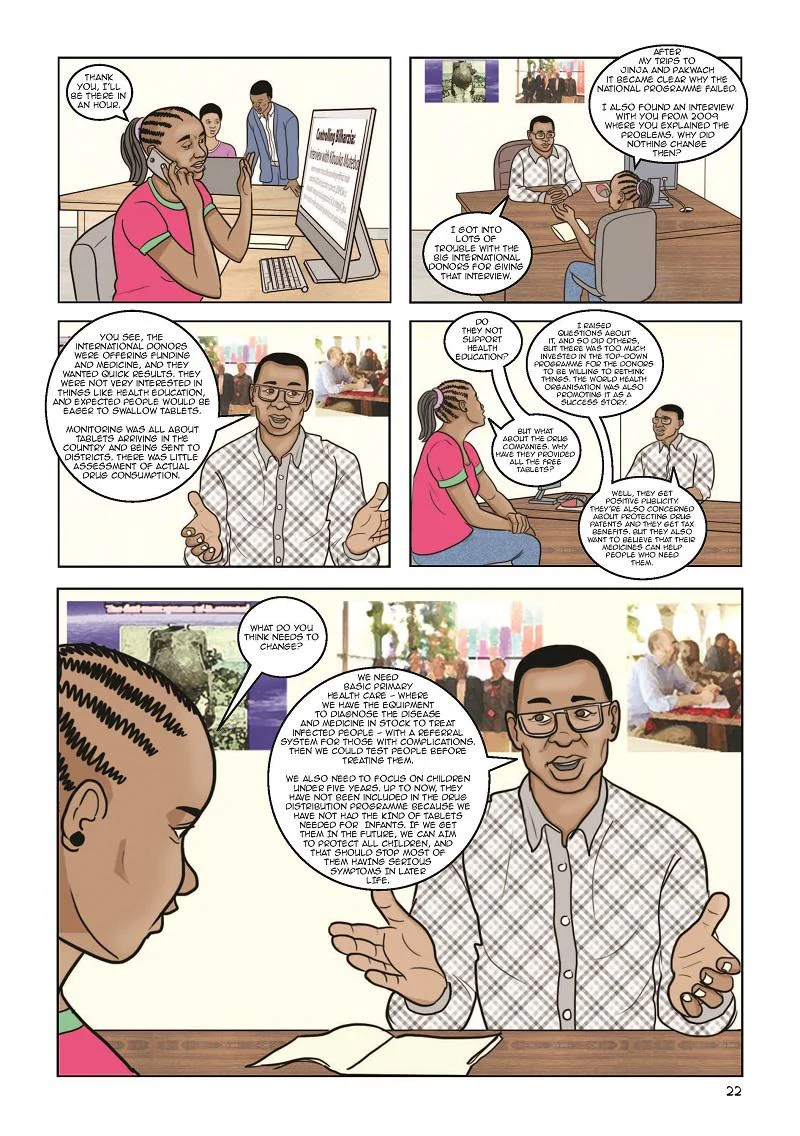

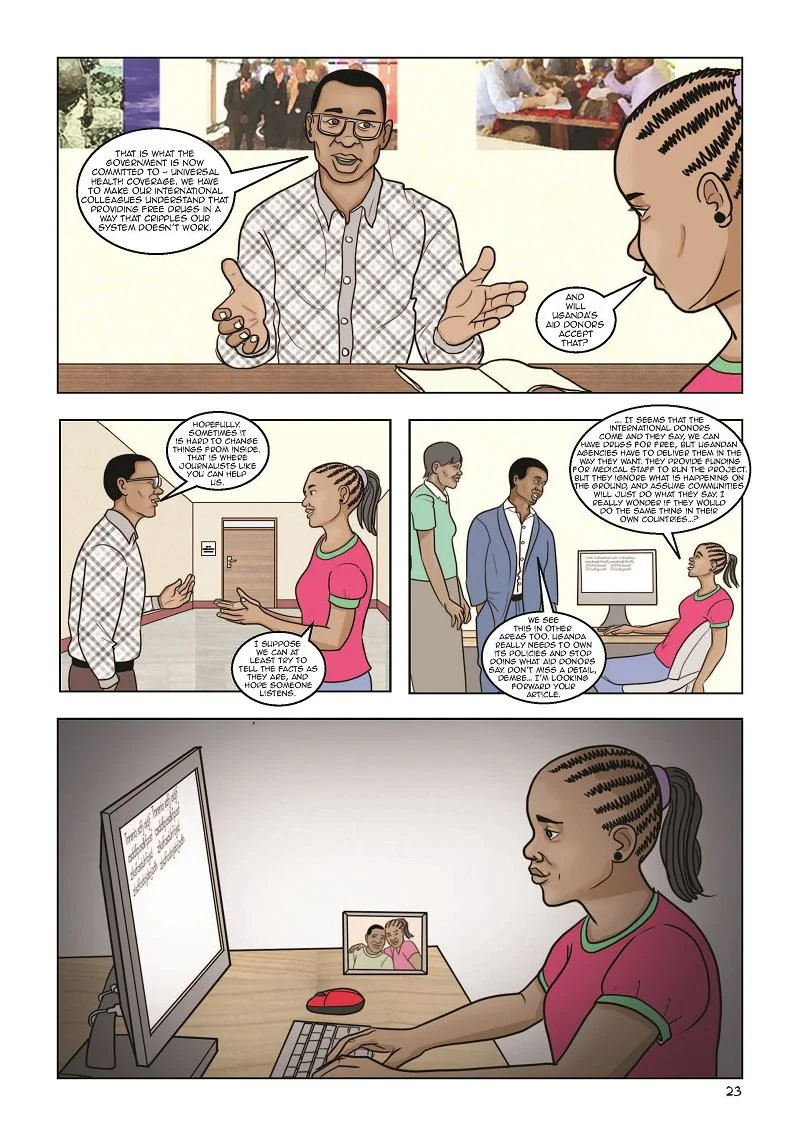

The breakdown in mass drug administration for bilharzia

CPAID comics series

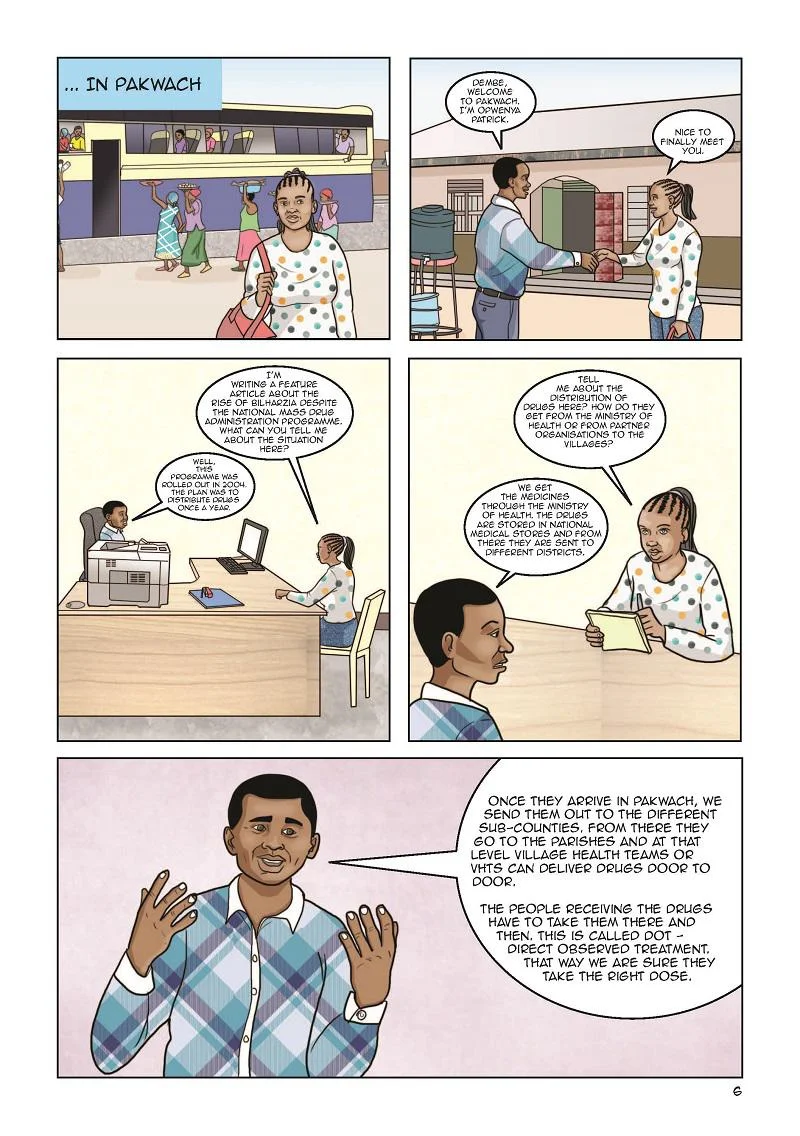

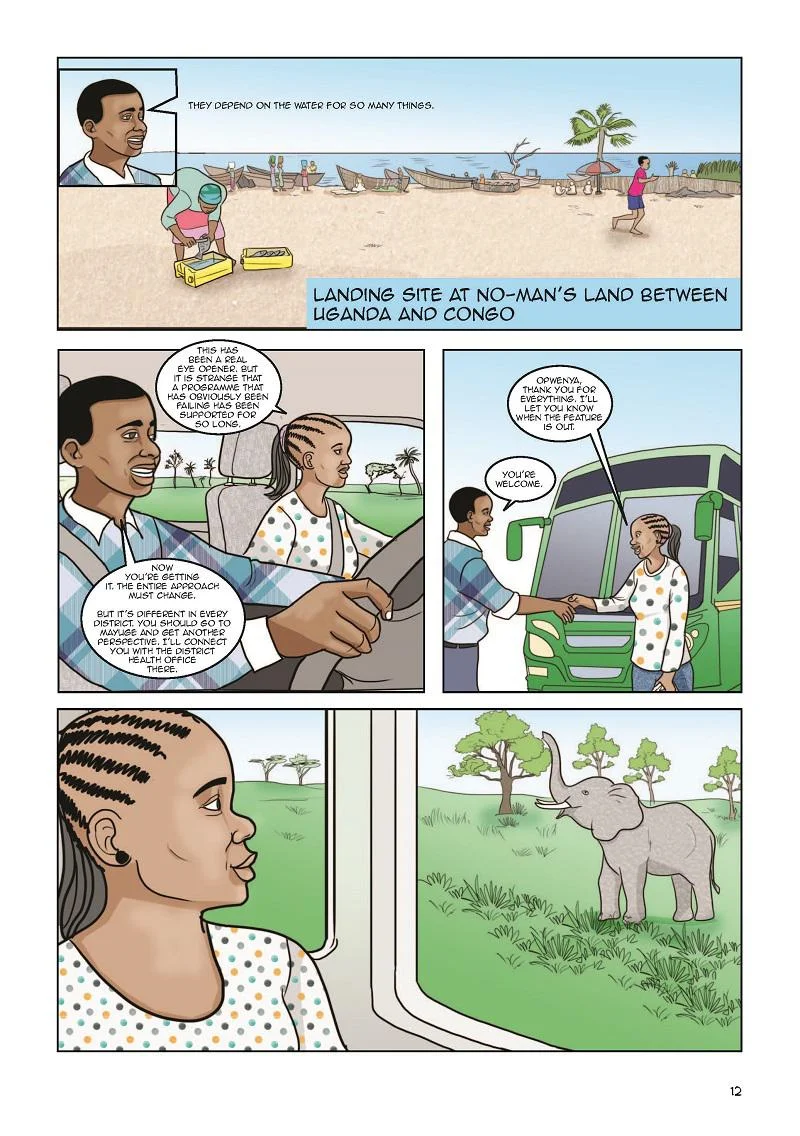

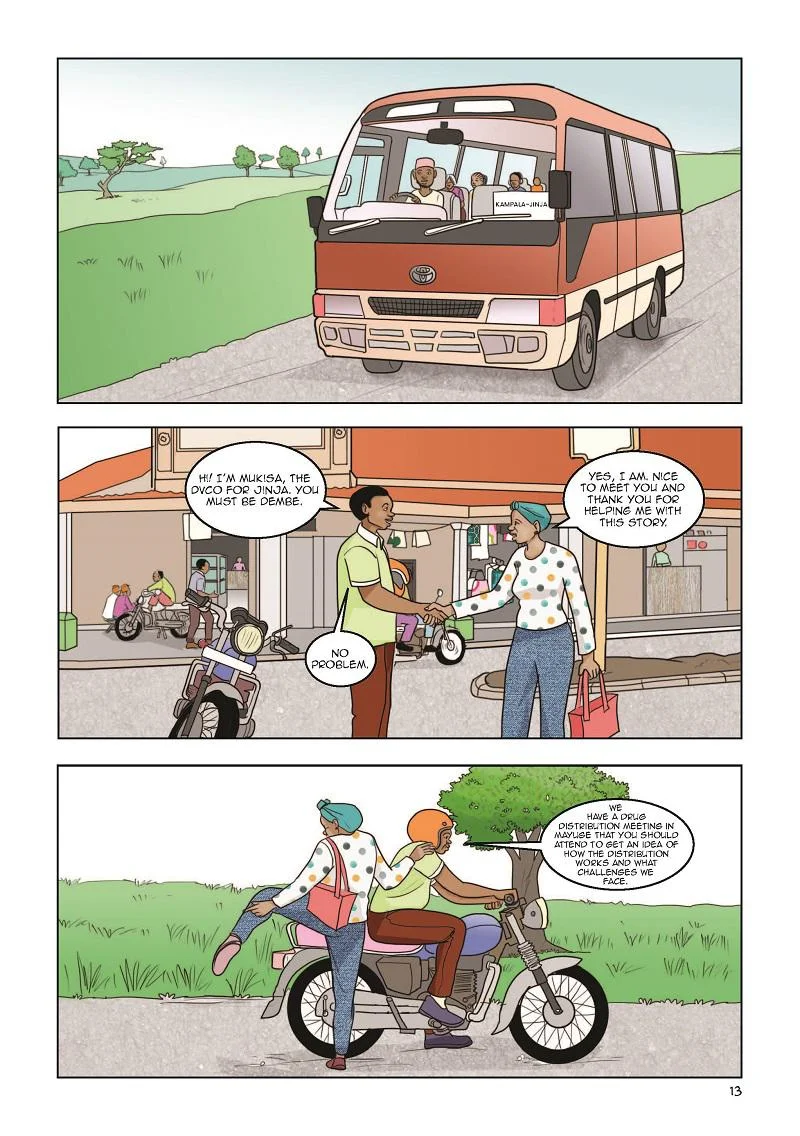

As part of a series of six comics on public authority across Africa, Ugandan artist Dianah Bwengye has collaborated with researcher Gloria Kiconco to illustrate why mass drug administration in Uganda has failed to adequately control schistosomiasis (bilharzia) in many areas. The cartoon contextualises issues raised by district health officers and local communities on health control programmes, following a trip to Jinja, on the northern shore of Lake Victoria, and Pakwach in the Uganda’s northwest.

View the comic below.

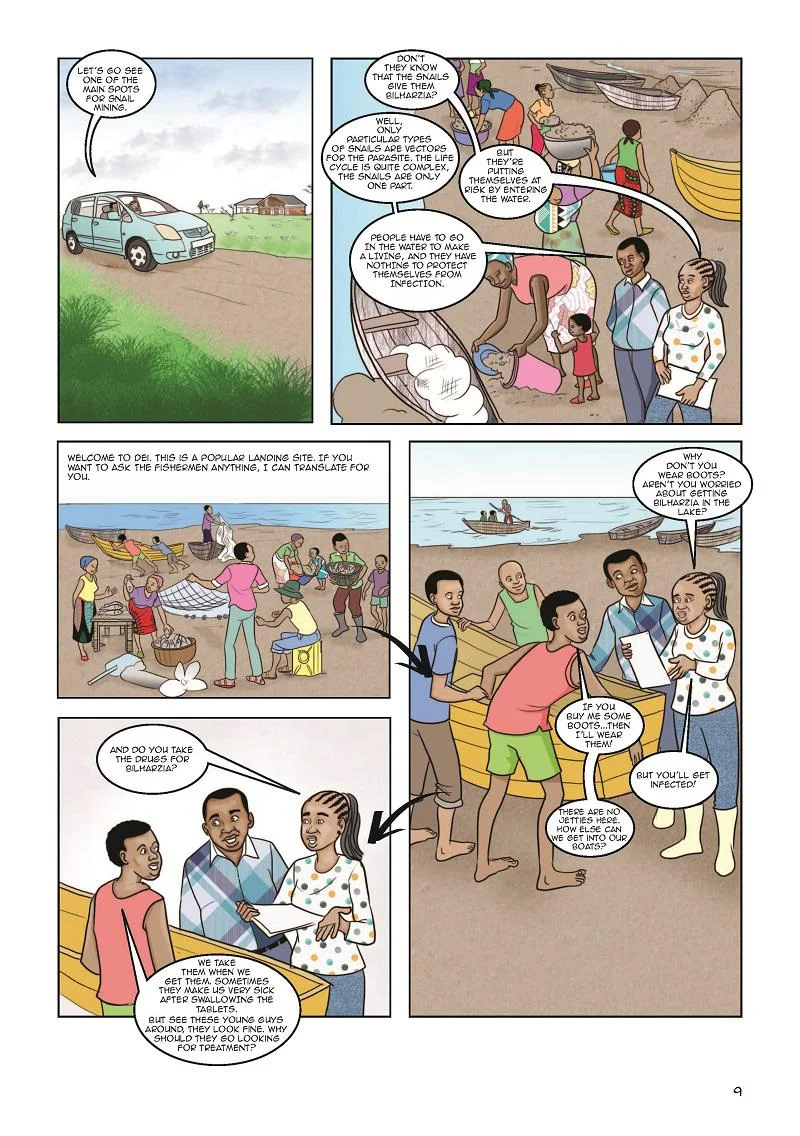

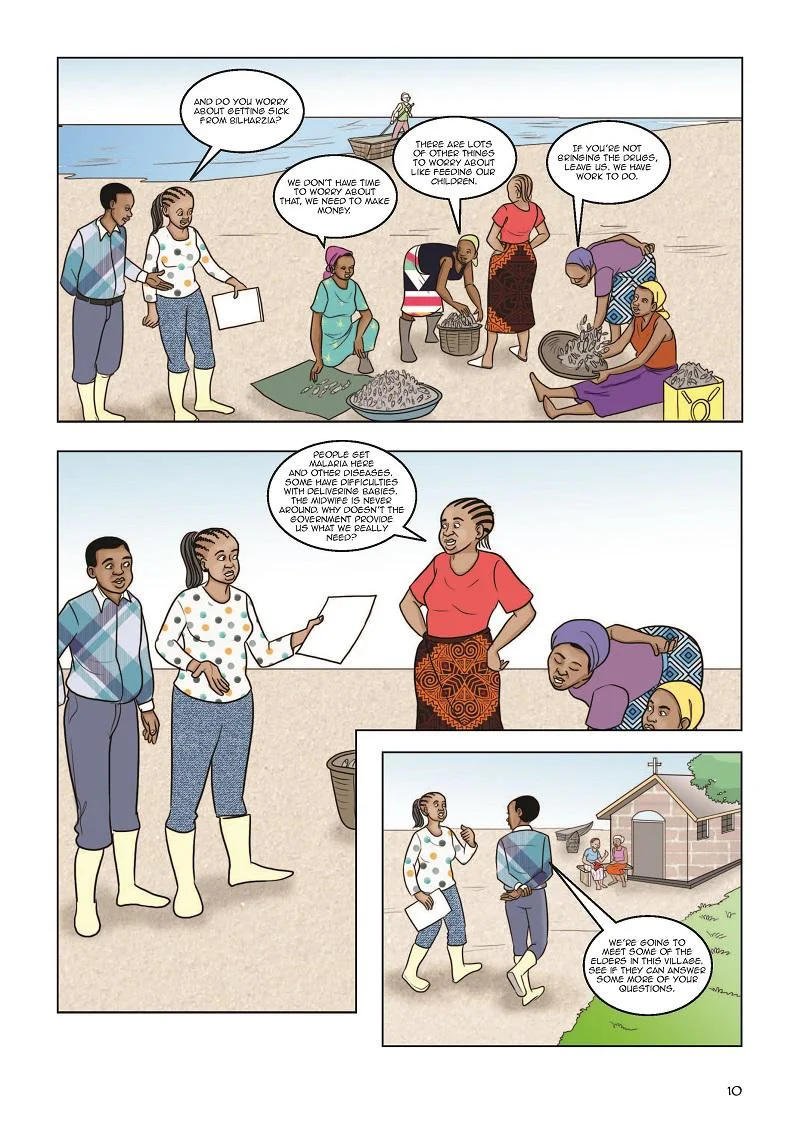

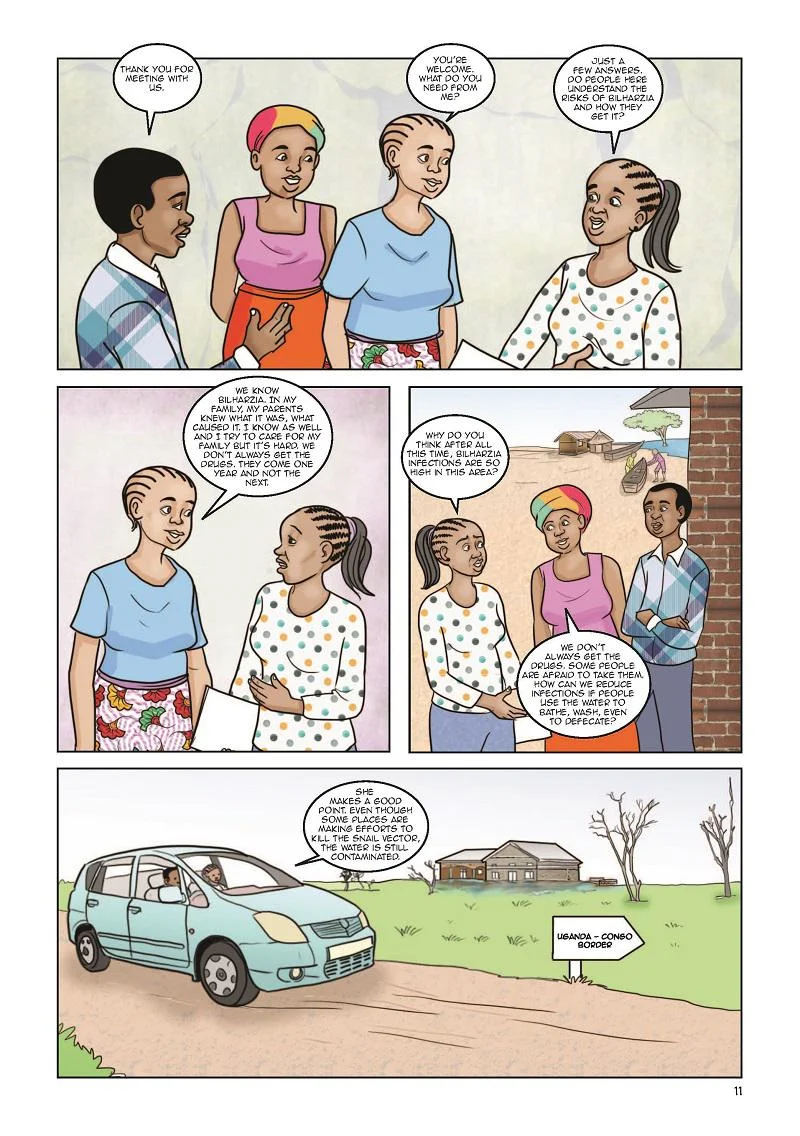

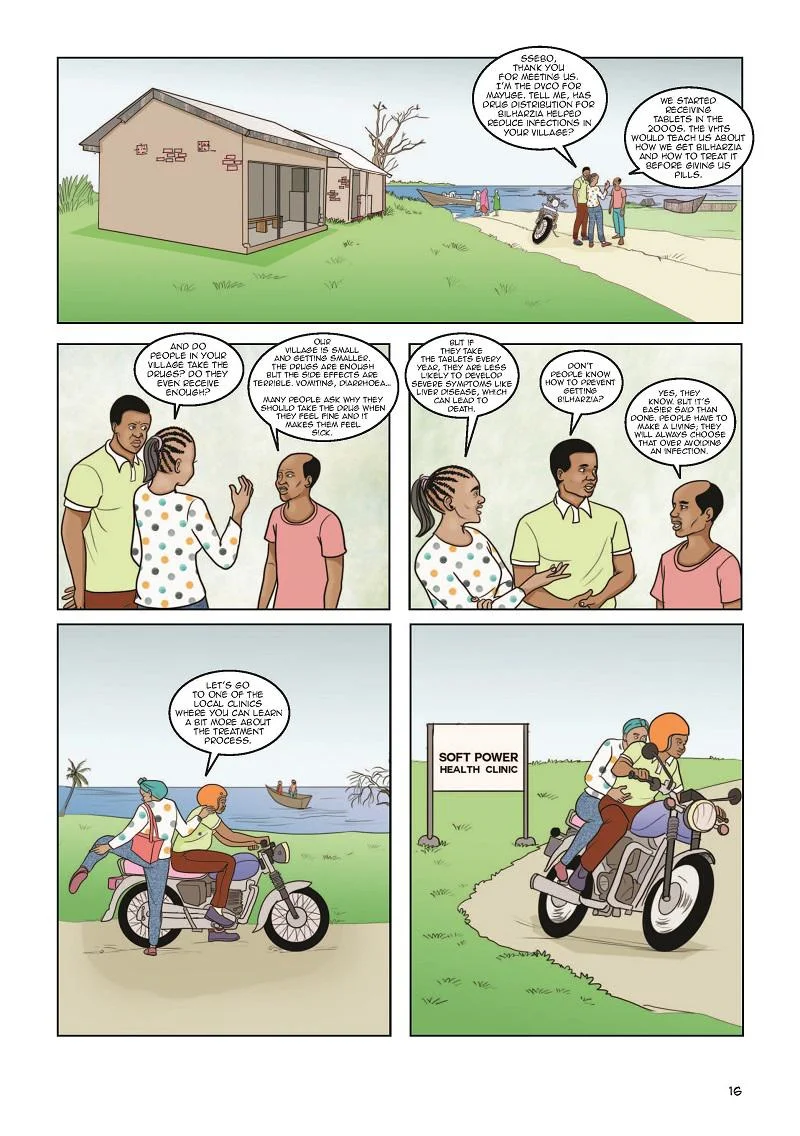

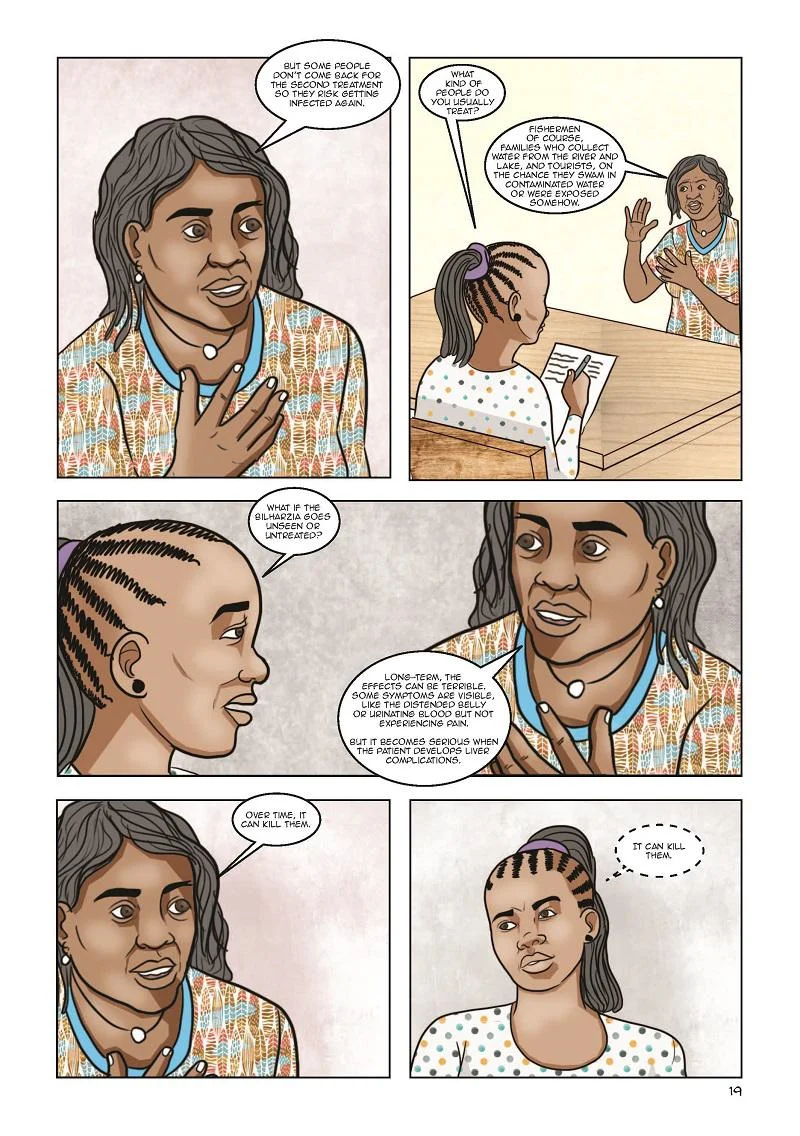

Current strategies have failed to account for the lived realities of people who rely on the water bodies, where the snail vectors involved in the parasite life cycle live.

Contextualising schistosomiasis (bilharzia) control efforts

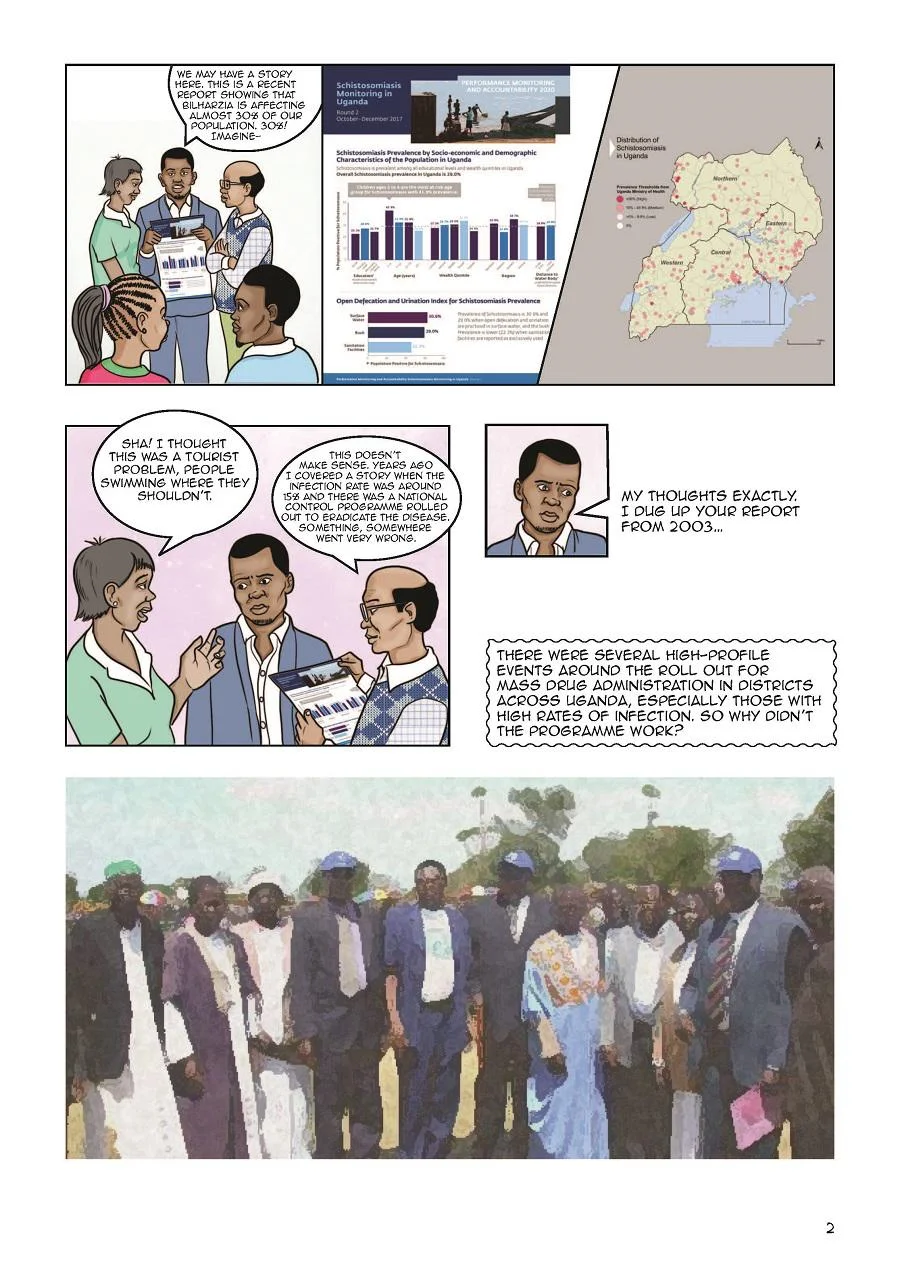

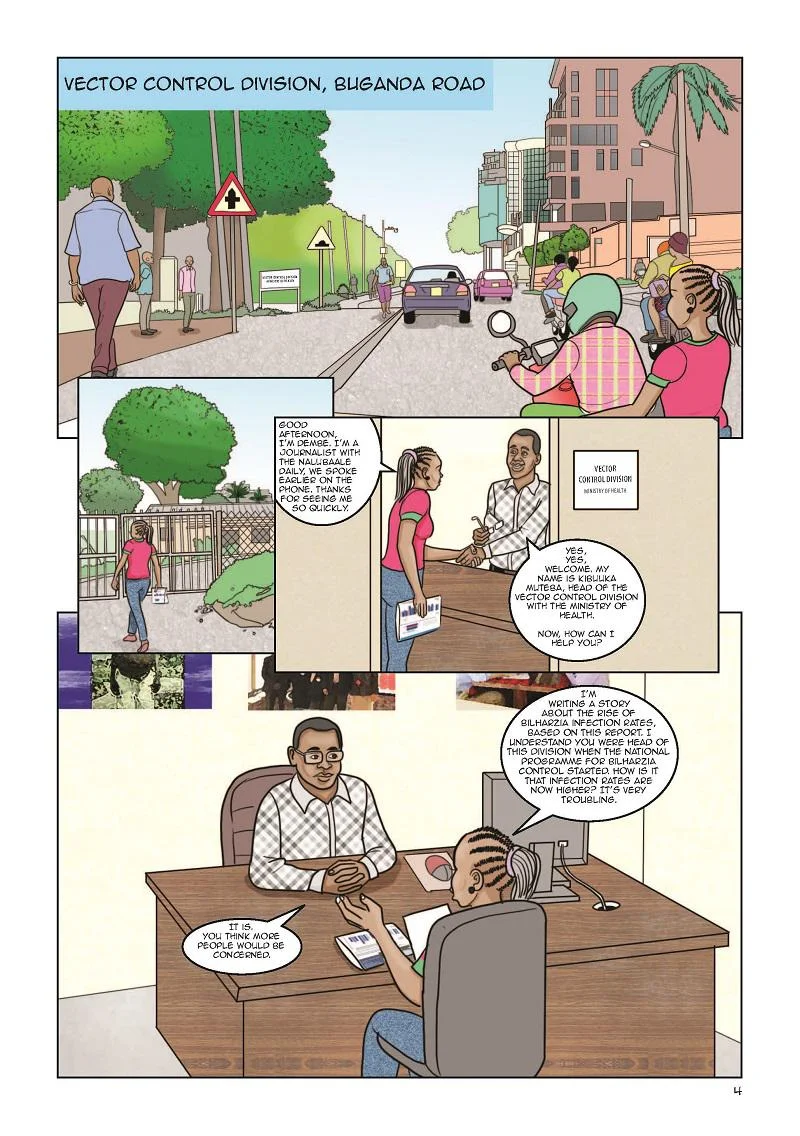

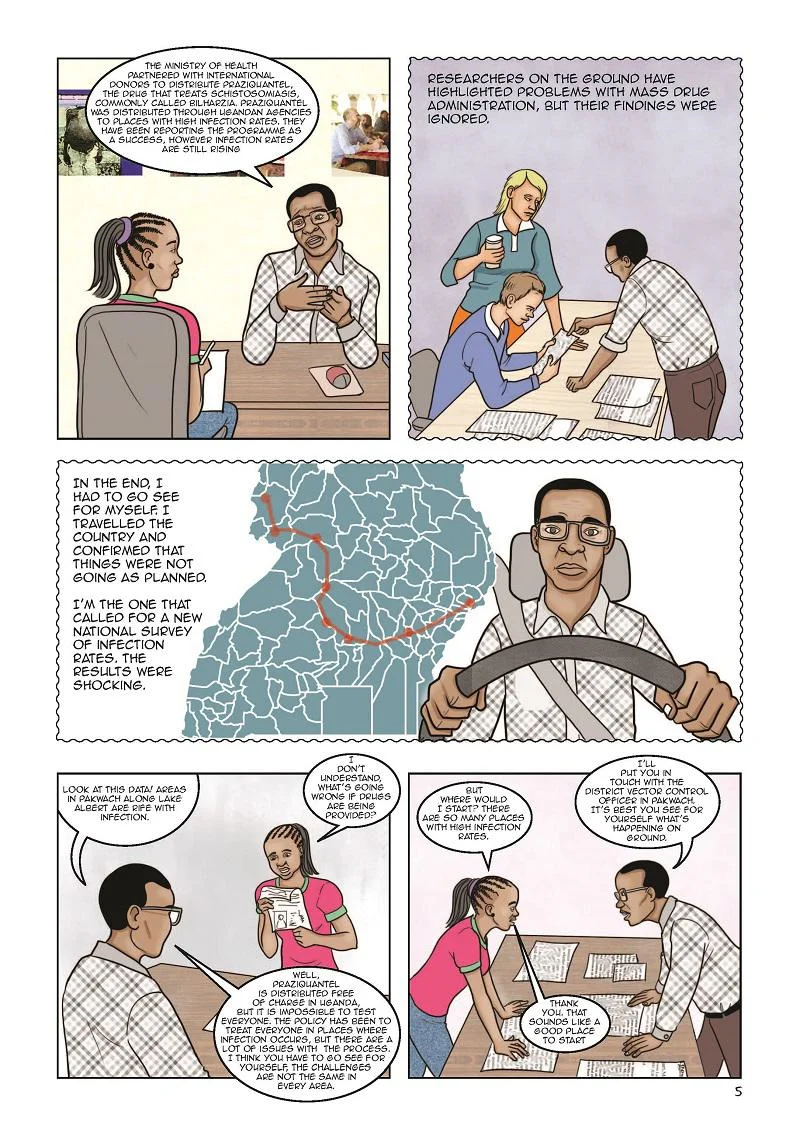

Weak Links tells the story of a journalist who seeks to find out more about mass drug administration in Uganda, after learning about the prevalence of schistosomiasis despite long-term health programmes. Hearing from local leaders, health-workers and fisherfolk, the story explains that providing pharmaceuticals without a deeper discussion on health and primary health care is ineffectual. Current strategies have failed to account for the lived realities of people who rely on the water bodies, where the snail vectors involved in the parasite life cycle live.

The comic includes public health knowledge that is tailored to Ugandan contexts. Artists Mirembe Musisi and Victor Ndula and two District Vector Control Officers in Uganda worked with members of the LEAD project team to produce a transmission diagram illustrating the life cycle of the schistosome. Included within the cartoon itself (page 7), the diagram and the story are intended as tools to disseminate contextually relevant knowledge about the transmission of schistosomiasis, and to recount the experiences of health workers who are responsible for the delivery of health interventions within communities affected.

Researchers: Georgina Pearson, Gloria Kiconco, Cristin Fergus, Tim Allen, Melissa Parker, Polly Savage and Kara Blackmore (project management)

This comic was created by Cartoon Movement, a publishing platform for high quality editorial cartoons and comics journalism from all over the globe.