Improving the efficiency of health services in antenatal care: the case of Mozambique

What was the problem?

The role of waiting times, how they affect perceptions of healthcare quality, and how this in turn affects demand for healthcare services and compliance with healthcare advice, has been under-studied in economics and in public health.

In the case of Mozambique, the provision of antenatal care faces particular challenges. While the vast majority (91 per cent) of women visit a health centre for antenatal care over the course of their pregnancy, only a little more than half (55 per cent) complete the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended minimum of four antenatal care visits. Even when they do receive enough visits, it is not always high-quality care. For example, only 43.6 per cent of women receive the necessary three doses of preventative treatment for malaria, just 51 per cent of HIV-positive pregnant women receive antiretroviral treatment, and only 18.6 per cent of HIV-positive pregnant women receive care to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

As in most developing countries, tools for managing patient flows, such as an appointment system, are almost non-existent. Patients typically arrive at a public clinic early in the morning and queue for several hours to be seen. On busy days, they may wait all day only to be turned away if it is over capacity.

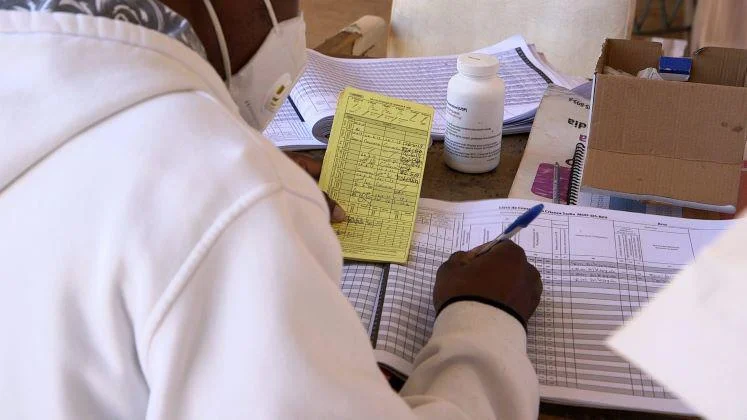

A crowded waiting area

Antenatal care is often the first interaction a pregnant woman has with the health centre. If her initial experience is negative and time-consuming, it is likely to have significant negative effects, including patients being less likely to follow medical advice or come back – including returning for delivery in the facility.

What did we do?

In 2014, with the support of the International Growth Centre, Dr Sandra Sequeira began a collaboration with the Ministry of Health in Mozambique to investigate whether reducing patient waiting times can increase the demand for healthcare and improve the quality of care.

Working with the National Institute of Health and the National Directorate of Public Health and Provincial Health Authorities, and in collaboration with the Harvard School of Public Health, Sequeira co-designed an appointment scheduling system for providing antenatal care. In 2016 and 2017, this was piloted and assessed in four high-volume urban and peri-urban clinics in southern Mozambique, covering over 8,000 patients.

For the pilot study, waiting time data were collected for 6,918 women. Average waiting times decreased by 100 minutes (a 41–53 per cent reduction) after appointment scheduling was introduced. This was particularly successful in clinics with higher volumes of patients.

Scheduling also increased the number of patients who received complete antenatal care during pregnancy (the WHO-recommended four visits). Among the cohort of women who attended the clinics during the pilot period for all 40 weeks of pregnancy, there was a 16-percentage-point increase in the number who attended for a minimum of four appointments. This study was the first to provide evidence that appointment scheduling can increase the use of public health services, suggesting that poor patient experience may contribute to poor health outcomes.

New appointment system

As part of the impact assessment, the researchers conducted 38 interviews at three clinics in southern Mozambique, with open-ended questions to explore patients’ experiences. The women interviewed felt it was important to seek antenatal care but encountered problems such as difficulty in arranging time off work or finding childcare. The scheduling system improved this experience by reducing time spent at the clinic and reducing uncertainty around timings.

Importantly, patients reported that healthcare workers were less stressed and more likely to have longer consultations that would include all routine procedures. Healthcare workers also reported improved working conditions. In interviews, nurses described how not having to manage a crowded waiting room has given them more time for other aspects of their work. The nurses were also able to strike a better work-life balance and reduce burnout and absenteeism. This suggests that a clinic’s management capacity can play an important role in shaping both the perceived and actual quality of care.

What happened?

Responding to the evidence from the study, Mozambique’s Ministry of Health made the scheduling strategy a national priority and part of its 2017 to 2022 strategic plan.

The Ministry asked the research team to help expand the intervention. It has since been rolled out across 46 antenatal care units on an experimental basis. Importantly, it has also been introduced in 40 HIV treatment units across three provinces in Mozambique. With an average of 1,500 antenatal care patients and 3,700 HIV patients enrolled in treatment in each facility, this represents an extension of the research initiative to cover more than 217,000 patients.

The HIV programme has the potential to have an even wider impact. HIV/AIDS remains one of the deadliest diseases in many sub-Saharan African countries. Mozambique has the eighth-highest HIV prevalence rate in the world (12.5 per cent in 2016). Despite recent progress in testing and starting patients living with HIV on antiretroviral treatment, low adherence to treatment threatens to undermine advances. Only 54 per cent of patients remain active in treatment after 12 months. Loss of treatment can increase the spread of the disease and intermittent treatment can build drug resistance, reversing past gains. Long waiting times to access regular care and collect medication are considered a major driver of low levels of HIV treatment.

The Mozambique government has allocated significant funds to support the scheduling expansion and a wider programme of capacity-building, to ensure its sustainability beyond the project timeline. The researchers have been funded to provide substantial technical training for staff at province and district level, who can in turn train nurses and clinicians at the facilities. This "training of trainers" will ensure continued feasibility and quality. The scheduling system has also been used to help to mitigate the strain on health facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Against the backdrop of rapid urbanisation across sub-Saharan Africa, the problem of overcrowded facilities and congestion is expected to be significantly exacerbated over the next 20 years. This intervention has been recognised as improving the management of public healthcare delivery in settings in which urban congestion and poor management of patient flows are constraints. The system is easily scalable and transferable to other healthcare settings, requiring minimal staff training and moderate financial resources. In recognition of this, the research team received a WHO competition award, with the committee noting the project’s: "strong potential to directly impact future work to reduce wait times and improve flow of care in the high-burden HIV clinic setting and other areas."

Banner and body images - credit Franco Sacchi