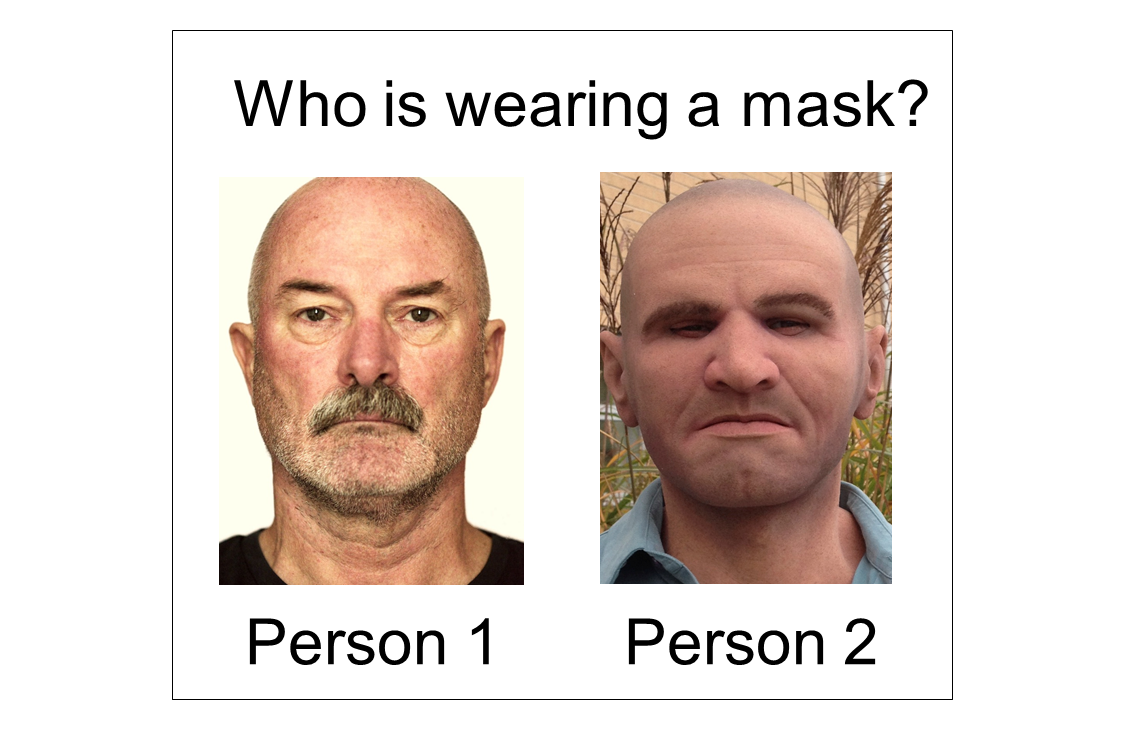

Some sillicone masks are now so realistic that they can easily be mistaken for real faces, research suggests.

In this study, led by Jet G. Sanders while at University of York (now Assistant Professor at LSE) and publised in Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, one-in-five people incorrectly guessed which was a real face and which was a hyper-realistic face mask when asked to compare two photographs side-by-side.

Failure to detect synthetic faces has important implications for crime prevention, notably how key characteristics of a persons' appearance may be incorrectly identified when a mask may have been used.

Dr Rob Jenkins with a hyper-realistic face mask. Image courtesy of Paul Shields, University of York

Dr Rob Jenkins with a hyper-realistic face mask. Image courtesy of Paul Shields, University of York

The study

Hyper-realistic face masks are made from a flexible sillicone material and are designed to imitate real human features all the way down to a tiny freckle and fine wrinkles.

In this study by the Universities of York and Kyoto, researchers asked participants to look at pairs of photographs; one of a normal face and one of a person wearing a hyper-realistic face mask. Participants were asked to indicate which of the two they thought to be the mask, with easily-detectable low-realism masks used as controls.

Surprisingly, participants got it wrong in one in five cases.

In studies such as these, limiting viewing duration is standard practice when a task may otherwise be too simple. To assess whether this may have been a limiting factor, the authors repeated the experiment with a new cohort and no time limit. For high-realism masks, responses were slower (1100 ms) and one in five participants incorrectly judged the real face to be the mask (20%).

Data were collected from participants from both the UK and Japan to establish any differences according to race. When asked to choose between photographs depicting faces of a different race to the trial participant, response times were approximately 400 ms slower and selections were 5% less accurate.

According to the researchers, this error rate likely underestimates the extent to which people may struggle to discern the difference when tested outside a lab setting, in everyday situations.

Author Dr Rob Jenkins (University of York) said:

"We made it clear to viewers that their task was to identify the mask in each pair of images. Example masks were shown before the test began. In a real-life situation, the error rate would likely be much higher than in our study as hyper-realistic masks are extremely rare and many people may not know they exist."

Dr Rob Jenkins (right) in a hyper-realistic face mask. Image courtesy of Paul Shields, University of York

Dr Rob Jenkins (right) in a hyper-realistic face mask. Image courtesy of Paul Shields, University of York

Use in criminal cases

Hyper-realistic face masks have most notably been used in criminal cases, with some criminals able to pass as a different age, gender or race. Being able to do so makes police invesitgations and identifications much harder.

According to Dr Sanders:

“Failure to detect synthetic faces may have important implications for security and crime prevention as hyper-realistic masks may allow the key characteristics of a persons’ appearance to be incorrectly identified.

“These masks currently cost around £1000 each and we expect them to become more widely used as advances in manufacturing make them more affordable.”

The authors suggest that further research should assess difficulties in identification between real faces and partial masks used to distort particular features and whether this may also be influenced by race.

The research is published in the open access journal Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications. It was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Sanders, J. G., Ueda, Y., Yoshikawa, S. et al, More Human than Human: a Turing test for photographed faces. Cogn. Research, 4, 43 (2019)