Are employment opportunities for ethnic minorities in the UK really improving? Fact checking the Sewell Report

Contents

- Claim: that overall there is a positive story to tell on the convergence of employment and pay between ethnic minorities and White British groups

- Claim: "geography, family influence, socio-economic background, culture and religion have more significant impact on life chances than the existence of racism." (p8)

In March 2021, the UK government released the anticipated report of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities. The paper, known as the Sewell Report, concluded that the UK does not have a problem with systemic racism, a claim that was immediately criticised, including by some academics referenced within the report. In its section on "Employment, Fairness at Work and Enterprise", the report gives the impression that inequalities in unemployment are falling over time and that racism plays a small role in such ethnic inequalities, relative to other factors to do with a person’s background. However, it does not present all the available evidence to justify that conclusion.

This article provides some context using estimates from the Labour Force Survey and suggests there is no such consistent improvement in unemployment disparities for ethnic minorities, and that discrimination remains an important factor for inequality.

When it came to unemployment gaps for women, our findings were all positive, indicating that all ethnic minority groups have higher unemployment rates than white women.

Claim: that overall there is a positive story to tell on the convergence of employment and pay between ethnic minorities and White British groups

In support of this claim, the Sewell report presents estimates of unadjusted (or raw) differences in unemployment rates over time but does not adjust these (or "control") for characteristics that are important in determining unemployment.

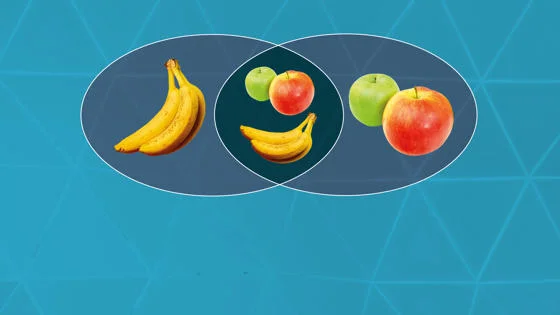

Adjustment is critical for having a meaningful comparison. For example, ethnic minorities are more likely to live in cities (where unemployment is relatively high) than the white population. The unadjusted unemployment differential could look larger than it really is if one does not take this into account.

To address this, we controlled for personal characteristics, including age, gender, qualifications, region, marital status, and dependent children. This provided us with estimates of unemployment within education groups. Though access to education may also be an important factor, this is something that happens outside the labour market and we were interested in how the labour market rewards qualifications.

We also restricted our sample to those born in the UK and considered the period 1995-2019 inclusive. To analyse long term trends, we studied the UK’s largest ethnic groups that have been consistently measured over this time; these are White, Black, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Chinese.

We first analysed the data on employment rates for women.

When it came to unemployment gaps for women, our findings were all positive, indicating that all ethnic minority groups have higher unemployment rates than white women, even when considering factors like geography and education. Only for Indians is the gap seen to be clearly declining over the past 25 years.

We then did the same for men.

Again, the data was all positive, indicating higher unemployment rates for ethnic minorities compared to whites. Only for Pakistanis did we find a clear decline in the unemployment penalty over the last 25 years.

The Sewell Report emphasises the importance of factors such as socio-economic background over racial bias in life chances, however it did not compare how large an impact these factors had in unemployment and pay disparities.

Claim: "geography, family influence, socio-economic background, culture and religion have more significant impact on life chances than the existence of racism." (p8)

The Sewell Report emphasises the importance of factors such as socio-economic background over racial bias in life chances, however it did not compare how large an impact these factors had in unemployment and pay disparities.

To fact check this claim, we adjusted unemployment gaps for the same personal characteristics, and also parent’s occupation (if they were unemployed or working in low-, medium- or high-qualification occupations), which allowed us to compare workers who grew up in the same socio-economic group. We also considered whether the person grew up in a single or no parent household.

Our findings are clear: parental occupation matters, with unemployment found to be greater for all socio-economic groups compared to the high-qualification occupational group. Coming from a single parent background does not seem to matter. But even after controlling for parental background, with the exception of Chinese women, we found that ethnic minorities continue to have higher unemployment rates.

Ethnic minorities from poor socio-economic backgrounds face a double penalty from their race and their background.

Figure 4 shows a similar picture for men. Some conclusions are similar to those for women; parental occupation matters but sizeable unemployment gaps for all ethnic minority groups remain. In contrast to women, however, men who grow up in single-parent families are found to be more likely to be unemployed in later life, though the gap is relatively small.

In addressing unemployment differentials, therefore, we find that both ethnicity and parental background seem to play a role and are problems that should be addressed. Ethnic minorities from poor socio-economic backgrounds face a double penalty from their race and their background. There is no reason to choose to focus on one and not the other; it is a false dichotomy to suggest that one should.

This empirical evidence does not tell us about the source of the unemployment differentials, but it does support the view that racial discrimination undoubtedly plays a role. The Sewell Report describes the results of the field experiments of job applications which control the content of the CV and show convincingly that having a name that suggests being from an ethnic minority lowers the probability of receiving a call-back. This is obviously unacceptable, and indeed the report does say that these studies provide conclusive evidence of bias in hiring and that this needs to be investigated further. Rather oddly, however, it then goes on to say that "these experiments cannot be relied upon to provide clarity on the extent that it happens in everyday life", despite the fact that they definitely can, because of the nature of the design of the experiment.

It is clear to us that more work is needed to understand the causes of ethnic minority penalties in the labour market and what can be done about them. We would suggest that a good place to start would be the scandal that your name influences your chances of getting a job interview (and probably a job).

Download a PDF version of this article