Worrall said that he does not publish a paper which is not epoch-making; publishing papers which do not make an epoch is immoral, or so he says […]

Imre Lakatos, in a letter to Paul Feyerabend, 10 January 1974.

Spinner is writing a three volume book on philosophy of science and he doesn’t have the faintest idea of what he is talking about. He has already finished the first volume. 600 pages. At the same time, there are people like Howson, Worrall and even Zahar, who are at least 250 times cleverer than he is, and know about 700 times more than he does, and still don’t care to write anything down, let alone three volumes […]

Imre Lakatos, in a letter to Paul Feyerabend, 21 December 1970.

The Story so far …

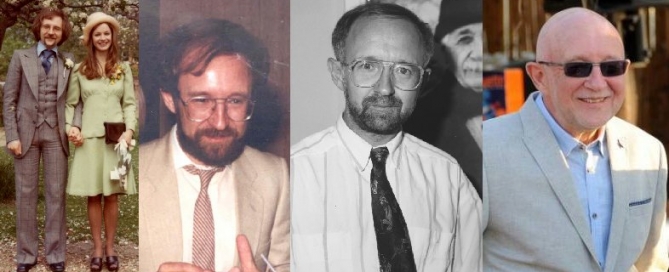

John Worrall “baby boomed” into existence on 27 November 1946 in Leigh, Lancashire – a town then dominated by cotton and coal. His father was a plumber and his mother and maternal grandmother were stalwarts of the local Methodist church, where John later taught in the Sunday School. He attended Leigh Grammar School and came to LSE in 1965 to study statistics. His aim was to be a (rich) actuary, though without knowing quite what actuaries did, and he became a philosopher by accident. Choosing logic in year 1, he attended some optional extra lectures by Karl Popper and was completely blown away. He switched wholesale to “Philosophy, Logic & Scientific Method”. He had the luck to be assigned Imre Lakatos as tutor. John’s first tutorial consisted of Lakatos giving him a list of books (including Courant & Robbins What is Mathematics?, Rogers Physics for the Inquiring Mind and Stoll Set Theory & Logic) and the instruction to come back when, and only when, he had worked through them all and completed all the exercises. When, to Lakatos’s evident surprise, John reappeared at the end of the term, complete with exercises, he was branded a “hopeful monster” and granted admission to the Lakatos Inner Circle. They did not see eye to eye on all things; Lakatos supported US involvement in Vietnam, and, more importantly, did not believe that would-be philosophers should waste energy on a social life and consequently made a regular habit of phoning John on Saturday evenings to talk philosophy for hours. But Imre set him on course for a PhD, made sure that he was appointed Lecturer in Philosophy in 1971, and above all provided an inspirational example of how to do serious philosophy. His sudden death in 1974 was a terrible blow.

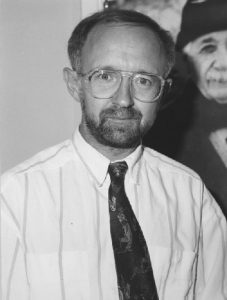

John has held a number of visiting fellowships (notably at Pittsburgh in 1982-83 at the invitation of Adolf Grünbaum), but otherwise his career has been at LSE. He met his wife of 40 years, Jennifer, there and they went on to have two beautiful children. John’s contributions to philosophy of science fall into three main areas: confirmation theory (especially the question of why predictive success should carry special evidential weight for a scientific theory), Structural Realism and the methodology of clinical trials (“evidence-based medicine”). He was for 10 years Editor of The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science and later elected President of the British Society for the Philosophy of Science. He succeeded John Watkins as Chair of the International Management Committee for the Lakatos Award in 1990.

John has played a full role in LSE life: he was Convenor of the Department for 3 years, was the founding Director of the Centre for Philosophy of the Natural and Social Sciences, and has served on most of the major School committees at one time or another. He has been a member of the Athletics Committee for over 30 years (20 years as Chair), and is currently Chair of the School’s Research Ethics Committee.

The Athletics Committee involvement stems from one of John’s passions: cricket. For 25 years, John served variously as Captain, Fixture Secretary and Team Secretary for the LSE Staff XI (some years all three at once) and spent many happy Wednesday afternoons at the sportsground in Berrylands. A wicketkeeper and (very stodgy) batsman, for some years he also played serious weekend cricket for Highgate CC. Having retired from the serious stuff, John continued to play for LSE well into his 50s – for the last several years, officially retiring at the end of one season, only to find himself (James Brown/Frank Sinatra-like and by popular demand) making a return at the start of the next.

Another passion is Liverpool FC: John has many happy memories of standing on the Kop in the 60s and 70s (though not such happy memories of the odd “Kop hot leg”). He was at Wembley to see “King Kenny” score the winning goal in the 1978 European Cup Final. He has never forgiven himself for not accepting an invitation to take a ticket for what turned out to be the “Miracle of Istanbul” in 2005 (courtesy of a former student who worked for AC Milan’s strategy unit so it would have meant sitting in the Milan end).

Rock and Roll challenges even cricket and Liverpool for John’s extra-curricular affection. He formed a group at school around 1960 – about the time The Beatles were getting together just a few miles down the road (though admittedly they were a bit better). John wanted the group to be called “In-sect”, but the others thought this was a silly name – any group name had to have a definite article – and they finished up (boringly) as “The Senators”. John left the group to revise for his A-levels, sold his guitar and hardly picked one up again until, as a consolation prize for turning 40, he bought himself the high-end Fender Stratocaster he had yearned for as a 16-year old. But the Strat mostly sat in state in its case until Alex Voorhoeve engineered a Departmental band to celebrate John’s 60th birthday. John lost out in the naming-stakes again: he suggested “Vi Agra and the Poppers” (their initial female singer – alongside Alex – was very much to the forefront) but again this didn’t go down well and they became The Critique of Pure Rhythm. Catch them at a Departmental Party near you.

So there it is: Philosophy – Science, Structure and Rock ‘n’ Roll!

Connect with us

Facebook

Twitter

Youtube

Flickr